When the Native Americans first came across white people on their land, they assumed that they were sent by God. And, when the same people first came across black people, their reactions were far from welcoming. The Mayans and the Aztecs exhibited similar reactions when they first saw white people, and that was one of the main reasons why the Europeans were so successful in making significant initial inroads into their territories, before eventually overpowering them. If native communities had different reactions to the white people or treated them as just another tribe that they were used to seeing on a regular basis, then they would not have allowed the Europeans to gain such a stranglehold on their lands.

That prompts the question as to how different world civilisations would have evolved if the color of the skin, along with hair and eyes, was consistent across geographies. In an alternate universe, if the skin color was white across all continents, then poems such as Rudyard Kipling’s The White Man’s Burden (exhorting the United States to assume colonial control of the Filipino people and their country), loaded with twisted and self-serving logic (giving the colonisers the license to kill with impunity and without any guilt all under the guise of serving a higher calling), would have still been written but would have been based on some other readily visible trait, say the straightness of nose or shape of the chin. Once enough of the population begins to associate a broader set of attributes, such as intelligence, bravery, strength, and power to that trait, then the rest of the population would follow implicitly. From that point on, all those with a straight nose (for example) would be considered intelligent, strong, or courageous, regardless of the real makeup or personality of that individual.

Let us look into a few examples — from ancient Greece, with very little awareness of other skin colors; from the Middle Ages, with moderate awareness of different skin colors; and from more contemporary times – to shed light on the ascent of the white color. In the History of the World, written around 300 BC, Herodotus talks about black people being similar to the Hellenic people, that is white people, except for the fact that their seed is greyer in color. He can be excused for being wrong on that front, about the color of black people’s seed, but he can be commended for the fact that he did not regard black people as inferior or consider them barbarians. Note that this interpretation is based on an early 19th-century English translation of Herodotus’ book; there is an outside chance that the translator might have tried to be politically correct and sanitized Herodotus’ actual words.

In Prince, written in the early 15th century, Machiavelli talks about Italians being the black people of Europe. It provides a glimpse into gradations of white, with the northern Europeans regarded as whiter than the southern ones. In the more recent A Troublesome Inheritance: Genes, Race, and Human History, Nicholas Wade proposes opening up the notion that there are three different races, or five, depending on the level of granularity one wants to get into, based on the readily discernible skull shapes—Afrikaans, Caucasians, and Mongoloids. Scientifically that is a fact, but does it have to lead to the immediate next question that pops up in most minds as they read that fact—if the skulls are different, does that mean one of them is better than the other? If no special attributes are implicitly assigned to any of the skull shapes, and they are just accepted as different skull shapes, no more, no less, then people of all skull shapes can coexist and each individual interaction is judged on a case-by-case basis rather than on stereotypes based on skull shapes.

In India, a country of over a billion people, with a diverse population in terms of hair colour (ranging from black to light brown), and of eye color (shades of black, brown, and green), there is one product that almost every Indian is aware of—Fair & Lovely, produced by Hindustan Lever, an Indian subsidiary of Unilever Corporation. Aside from the fact that it is a huge testament to the marketing geniuses behind that product, Fair & Lovely has carved out a huge market selling “fairness” — another term for white skin in India — to the population. It promises to make the skin a couple of shades lighter through its use over just a few weeks. This may seem like a politically incorrect statement in the United States (and potentially in some European countries) but it does not cause any controversy in India. Everybody accepts it as part of life and mostly, girls with darker complexions continue to use it in the hope of making their skin tone lighter. Do these 1.1 billion people validate that white or fair is the desired colour? Are we instinctively wired to regard white as good and black as bad or is there something else going on here?

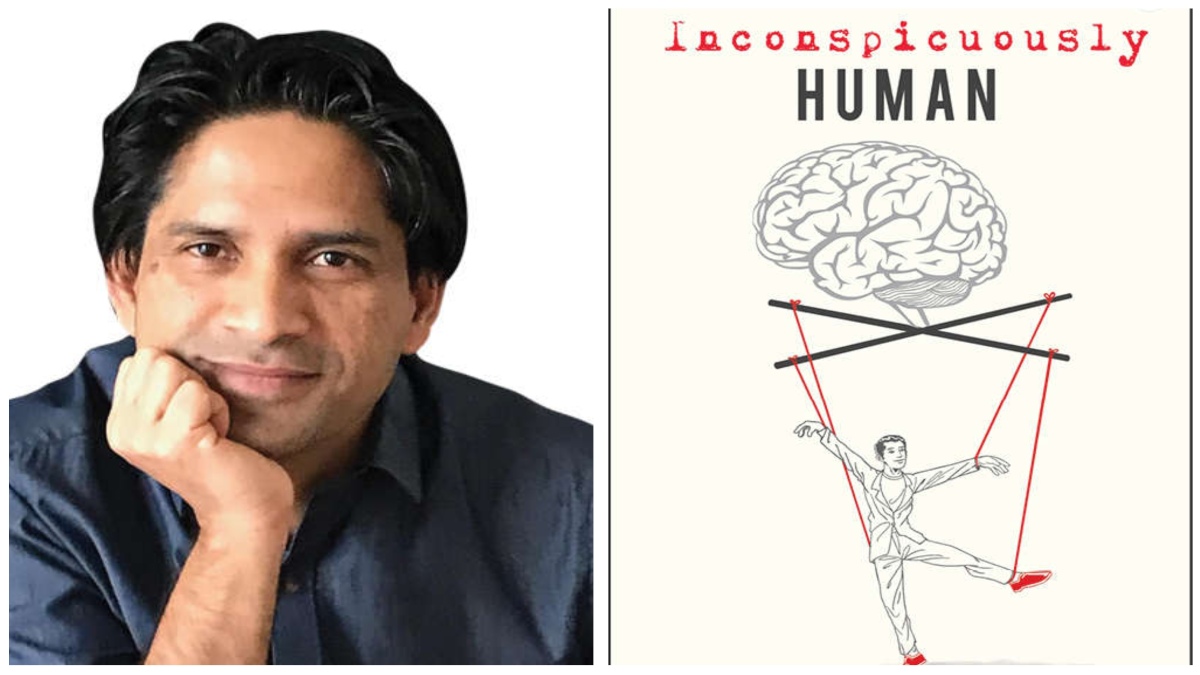

The excerpt is from the book ‘Inconspicuously Human’ (published by The AlcovePublishers).