The economic fallout from the pandemic has hit a critical component of India’s economy. With disrupted cash cycles, plummeting revenues with a thin resource-cushion to bank on, MSMEs are mired in a slump. The micro, small and medium enterprises (MSME) form the lifeblood of the Indian economy by employing over 11 crore people, second only to agriculture, and contributing a third of the GDP. Driving the thick of growth and employment, especially for vulnerable segments of the workforce in the non-agricultural sector, with low capital costs, somehow this sector hasn’t received the attention and assistance it deserves.

MSMEs hold the promise to propel India’s development arc as evinced by the growth model of successful Southeast Asian economies. But policy assistance and reforms to overcome existing bottlenecks and practical difficulties with a focus on charting a sustainable course will be a critical enabler for realising their potential. In this context, although credit injection and regulatory reliefs have stepped in to backstop this decline, policy responses shouldn’t be aimed only at weathering the current crisis, but also to sustain growth once these enterprises recover.

Planning focus for a medium to long-term growth trajectory for MSMEs would require a three-pronged strategy of absorption, transition and innovation, with recognition of the heterogeneous components of this sector.

ABSORPTION

The Indian workforce needs an exit strategy from the low productivity and underemployed agricultural sector. The lower rung of MSMEs can emerge as an attractive prospect, provided we get certain things right.

Absorption can only take place if good jobs open up in sizable numbers at the lower end of skill requirements. The need is to target and expand MSMEs in the labour-intensive ‘manufacturing’ sector which has an unrealized potential as MSMEs contribute only 6% of manufacturing GDP, in contrast with services, which contribute 24%. Part of the issue has to do with the fragmented manufacturing bodies which yield low returns to capital and thus attract little autonomous investment. Filliping this component of MSMEs will be indispensable as India can’t leapfrog manufacturing if it aims to achieve sustainable broad-based growth.

Fostering broad-based entrepreneurship across the country will open up alternative avenues and enable the absorption from the primary sector. The critical factor here will be easing and extending financing access for MSMEs. Due to the informal nature of these enterprises, and asymmetrical information for institutional lenders, financing entrepreneurial activities has been broadly a challenge—only 16% of MSMEs receive formal credit. Given the heterogeneous composition of MSMEs, a ‘one size fits all’ financing strategy is unfeasible, hence, the government’s efforts to address financing need contextualisation. For instance, providing seed capital for micro enterprises, encouraging easy financial assistance to women entrepreneurs through small banks’ whose MFI have a women-dominant clientele, and removing regulatory impediments to access venture capital for promising medium size enterprises could help achieve lending efficiencies.

Besides resource access, a definite marketplace for MSME output is equally essential. Expanding the public procurement policy’s reach through platforms such as Government e Marketplace (GeM) is pressing. A practical difficulty in the current scenario is the tedious tendering process where tiny enterprises face roadblocks to participate and thus avail of government procurement. Navigating the large business-political nexus to grab tenders and sustaining through the lengthy procedures is a challenge for small scale enterprises. The other dire challenge of the lack of formalisation is because of low registration in Udyog Aadhar Memorandum, which mature enterprises with proven track record easily avail of. Widespread implementation by easy registration in a flexible regulatory framework to rope in tiny enterprises is needed to make their entry into the formal economy.

TRANSITION

A peculiar attribute of Indian MSMEs is that the majority (around 96%) of them comprise micro (employing only 5 or fewer workers) and small-scale enterprises which provide tepid employment opportunities. Tapping into this ‘missing middle’ of the industrial structure, would be critical for generating productive employment. The transition would require policy encouragements in the form of enhanced formal credit for successful tiny enterprises to mature into medium size. This is pressing because small enterprises cannot operate productively, let alone efficiently, and thus most micro enterprises in our country fail to grow. Developing capabilities through scale should be the way forward.

There are well auguring prospects for medium enterprises to integrate themselves with global value chains as “demographical reversal” and increasing wages in early growers like China has made room for other countries to avail of the lacunae. And the avenue to look at is in ‘manufacturing’, as Arvind Subramanian shows in his paper that India is vastly under-exporting relative to its labour force, and big, unexploited opportunities lie in unskilled labour exports. A McKinsey report also states that there is an export growth potential of $70 billion in manufacturing alone. But to capitalize on this, MSMEs need to grow in their operations to avail of scale economies and operate at peak efficiency. Policy enablers for this transition are needed in the form of enabling trade deals with global partners, progressive regulatory reductions, and reformed labour laws making it easier for mid-size firms to hire workers unhesitatingly.

More than half (around 51%) of the MSMEs are located in rural areas. The case for sustained impetus to this sector is even more pressing now because the upshot of a reverse migration during the last year due to Covid, has made available a semi-skilled workforce which can be engaged in productive employment as MSMEs recover and make room through expansion. MSMEs can serve to provide economic empowerment to the rural populations while also allaying regional disparities. The ethos aligns with the goal of achieving inclusive growth for India, advancing people through upward mobility and expanding the middle class, which, in a world of growth stagnation, will be a resilient driver for domestic growth. In this context, India can learn from the opportune case of Shenzen in China, wherein the municipal governments intervened and heavily assisted the transformation of a rural area into an urban startup hub.

A lot will depend on the extent of cooperative federalism India can secure, especially now, because after the woes of GST, the federal relations are stretched more than ever, and need essential repair. This is vital so as to ensure vertical fund flows and tackle the constitutional concurrent subject of labour laws. There is a need to give states more flexibility with regard to tax revenues which would be critical to ensure the growth of regional MSMEs because a decentralized flexible system can allocate funds better, just like the Shenzen’s experience evinces.

INNOVATION

Any growth strategy won’t sustain itself on its own in a dynamic business environment. Besides, only frugal labour and financing credit won’t be enough for MSMEs to create an edge in international markets. The MSME sector in India is beset with technological inadequacy. Looking ahead, to enable sustained growth and facilitate MSMEs to move upwards in the value chain, the service sector would be pivotal.

India must leverage its attractive ICT capabilities and lure a higher amount of FDI in the service sector to scale up and ameliorate its current station. Innovation and digitisation are indispensable if Indian MSMEs want to remain competitive through increased efficacy and agility. A Microsoft report concludes that adoption of the latest ICT tools can help India’s small and medium businesses boost revenues by $56 billion, while also creating over a million jobs.

The year 2020 witnessed the accelerated adoption of digital behaviours and practices by enterprises, from sales channels to communication, and, as a CRISIL report suggests, this increasing digitalisation will enlarge the footprint of MSMEs, helping them tap into newer markets and improving their access to credit. However, since most MSMEs operate in the informal economy with low capital base, policy enablers for innovation will be vital for long-term sustenance in a transforming business environment. These enterprises face both internal resource constraints due to their size and external constraints to credit access due to market failures.

R&D investments by SMEs need to be encouraged and bolstered by policy support and incentives. A key support for this could be inspired by the model from Europe through new public innovation support programs. As the enterprises mature, investment in analytics would necessitate a skilled workforce for the service sector, and government efforts in reskilling and upskilling would serve the twin benefits of assisting MSMEs and realising the promise of India’s demographic dividend. Useful lessons can be drawn from Germany, which has successfully built a national culture wherein vocational training is seen as a valued career path.

MSMEs have an unrealised promise yet somehow it doesn’t capture the popular imagination as much as it deserves. We would be leaving money on the table, if we don’t realize this key determinant for India’s growth story in the coming decade. It is high time the crucial backbone of India’s story deserves its fate and its cause is assisted by involved stakeholders driving policy forward with focus on medium to long-term growth.

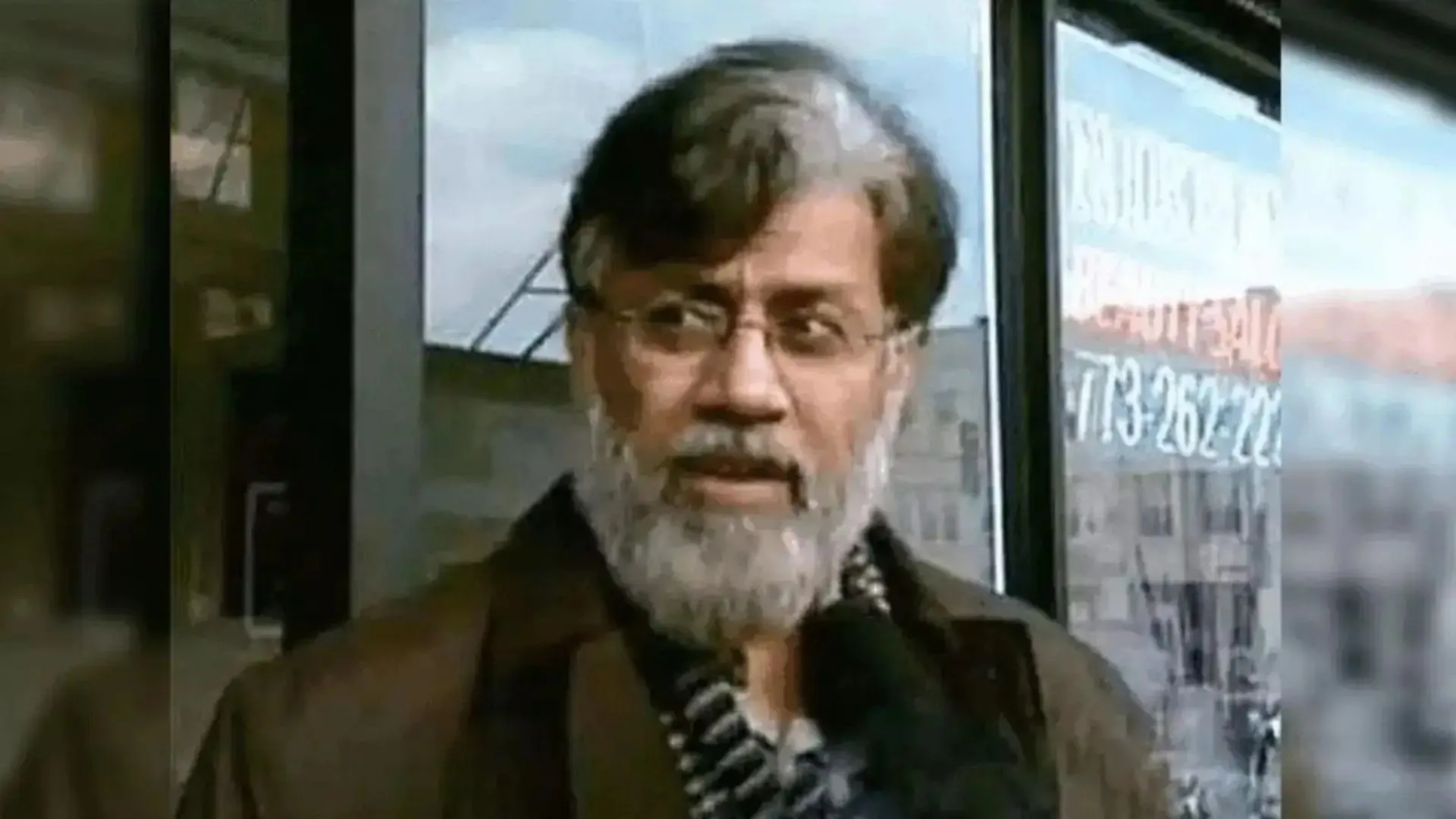

Rajesh Mehta is a leading international consultant and columnist working on market entry, innovation and public policy. Govind Gupta is the co-founder of IFSA Hansraj and a researcher at Infinite Sum Modeling, Washington.