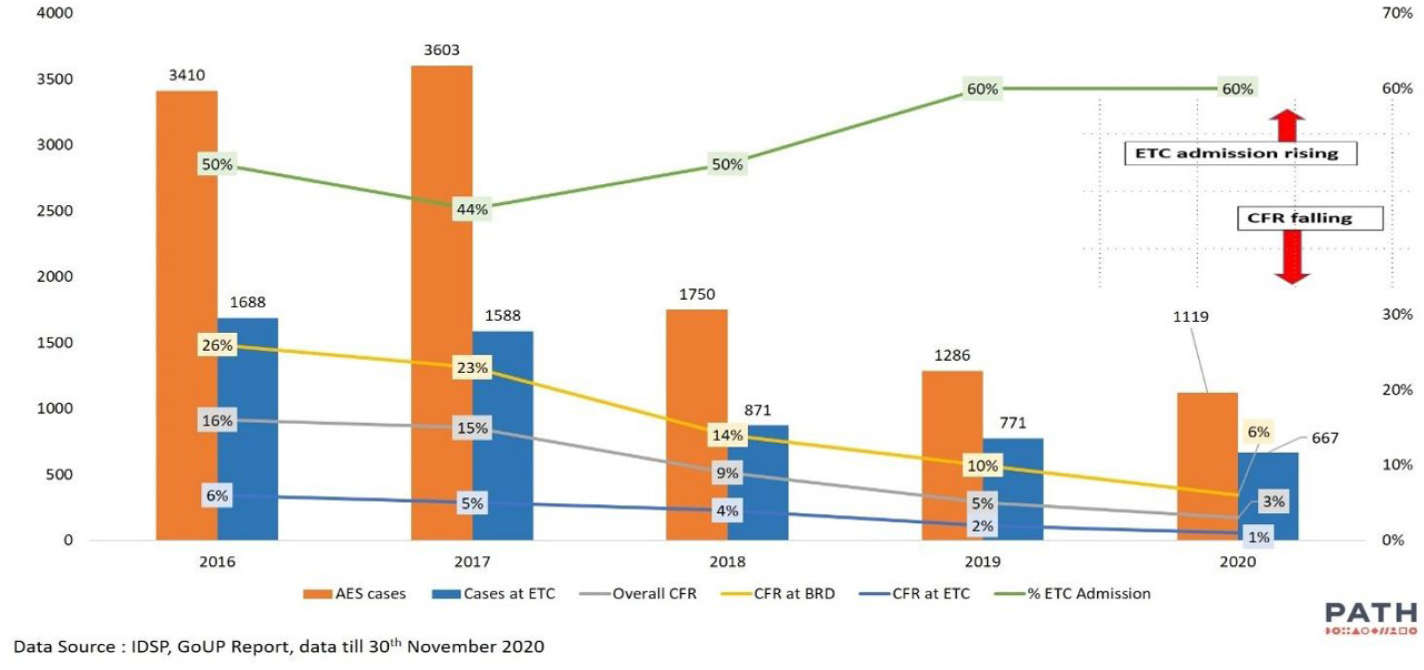

A cute Encephalitis Syndrome (AES) is a fatal disease that has plagued Uttar Pradesh (UP) for decades, with annual outbreaks reported since 1977. The Japanese Encephalitis ( JE) virus, endemic to at least 38 districts of eastern and central UP, is a prominent source of encephalitis deaths in the state, causing 600- 1000 deaths annually. In 2005-2018, there were over 47,000 AES cases reported in UP, resulting in more than 8000 deaths. However, in 2019, the number of AES cases in the state reduced by nearly 68% and deaths reduced by 88%, when compared to 2017. Cut to 2020, when AES deaths have reduced even further by almost 95%. The analysis of data from Gorakhpur and Basti districts by the international non-profit PATH has revealed this welcome trend.

Amidst allegations of data manipulation in the media over the last three years, we attempt an objective assessment of the available data as well as the UP government’s new approach to tackle AES/JE cases. This multi-pronged approach supplements immunisation programmes for children with a new door-todoor awareness campaign called Dastak. Additionally, efforts have been made to strengthen public healthcare facilities to ensure that patients receive treatment in the fastest possible time, resulting in the response time for managing AES to decrease by almost 80%.

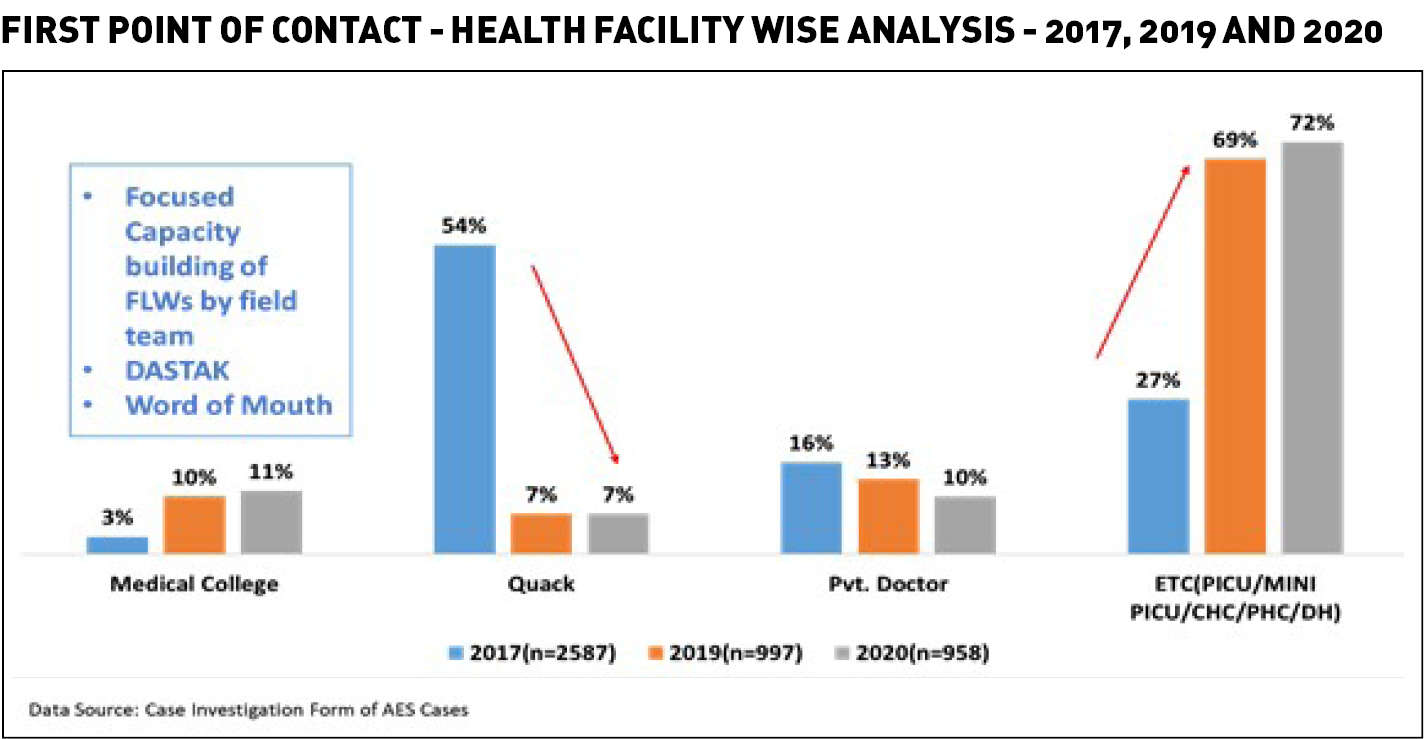

As per a survey conducted in 2016-17, before the intervention, about 54% of AES patients were approaching informal healthcare providers for treatment. To make treatment readily accessible at the nearest location, the government upgraded 104 primary and secondary facilities to function as 24×7 Encephalitis Treatment Centres (ETCs). While these ETCs were supplemented with trained staff, essential drugs and equipment to ensure proper treatment at the block level, the government also equipped district hospitals with paediatric intensive care units (PICU) and trained specialists to deal with treatment complications. Standardized checklists were developed to gauge problems and ensure corrective actions. By 2020, the number of patients approaching quacks declined to 7%, while those approaching ETCs jumped to 72%.

Prior to 2017, Baba Raghav Das (BRD) Medical College in Gorakhpur was the only healthcare facility for paediatric patients suffering from AES/JE. Notably, the facility came under the media spotlight back in 2017 after the deaths of several children, allegedly due to a shortage of oxygen supply. The same year, to address the issue of the non-availability of treatment facilities at the block level, which often led to delays in treatment, a system of mini PICUs was set up. Paediatricians, medical officers, PICU-trained nurses and essential equipment, including ventilators, were made available at the mini PICUs for early management of encephalitis cases. Early detection and treatment through mini PICUs seem to have not only controlled disabilities and deaths among the patients, but also aided in reducing the case burden on BRD Medical College.

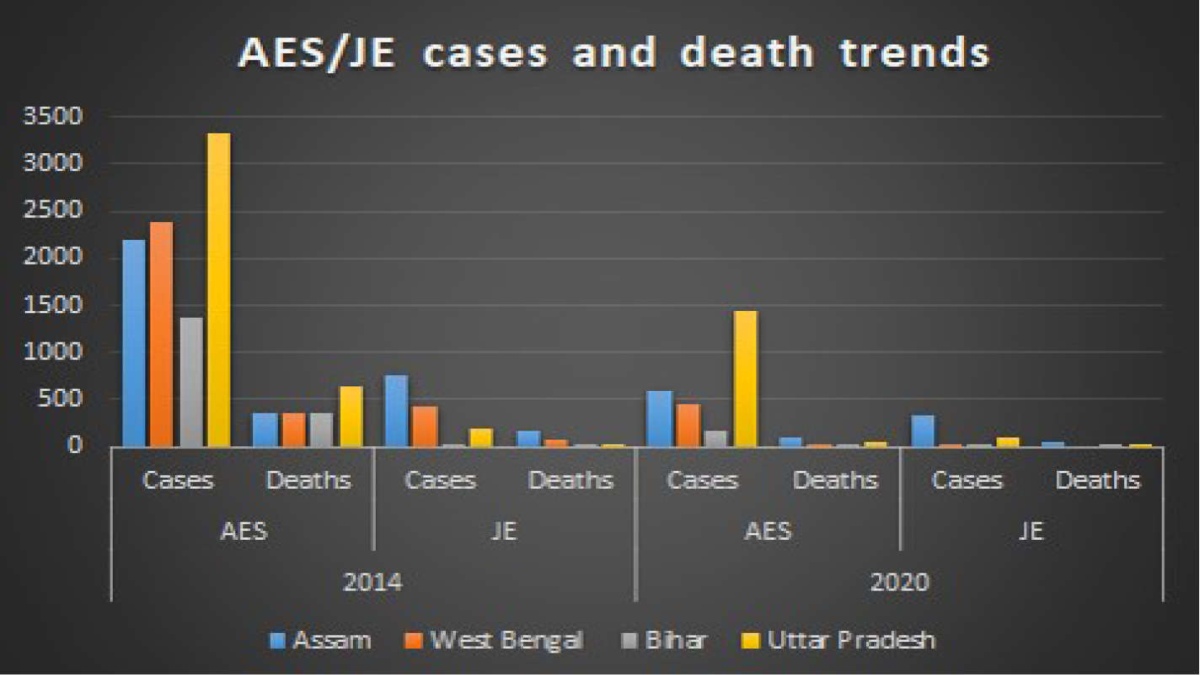

At the heart of the state’s new strategy is the UNICEFaided Dastak campaign, under which, frontline healthcare workers, ASHA and Anganwadi workers are deployed for door-to-door sensitisation of individuals, with a greater focus on 617 villages with a higher risk of AES/JE. An assessment of the Dastak campaign revealed that more than 8 million houses were visited by ASHA workers for sensitisation in 2019, which seems to have decisively impacted fatalities. In fact, the mechanism developed for capturing the Dastak campaign data may have also played a crucial role in the state’s management of the COVID pandemic. Village-level sensitisation by frontline workers has been key for the containment of COVID after a large influx of returning migrants during the period. The state’s awarenessbuilding efforts have also included an increased engagement through mass media, social media, and workshops supported by UNICEF and PATH. The impact of the awareness programmes can be gauged to a certain extent by looking at the average days between the onset of symptoms to admission, which decreased from 5 days in 2017 to 0.9 days in 2020. Further, the government is leveraging the reach which schools have by nominating health educators to spread awareness about health, sanitation, and AES prevention and control among students, parents and teachers. Additionally, a mass behaviour change intervention, called the Sanchari Rog Niyantran Abhiyan (SRNA), is being implemented, under which, 12 state departments have conducted inter-departmental activities, trained frontline workers and generated public awareness. SRNA activities in 2019 included, inter alia, about 5,31,281 school rallies, 1,82,104 sensitisation meetings and 7,40,188 drainage clearances in rural areas. Mass vaccination campaigns for JE were first introduced in the state in 2006. However, their impact was limited owing to low coverage and lack of awareness. Immunisation efforts were intensified in 2017 with the introduction of two doses of the JE vaccine for children aged 9-12 months and 16-24 months, followed by routine immunization. In March 2020, the state government launched a follow-up vaccination drive to ensure the immunization of those who had been missed earlier, a strategy that has been lauded by UNICEF. It is to be noted here that the decline in cases in UP is in tandem with similar trends in other states and nationally. Data from the National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme (NVBDCP) shows that cases and mortality rates have gone down since 2014.

The national death count of AES and JE cases declined from 1,719 and 293 in 2014 to 199 and 68 in 2020, respectively. However, since much of India’s AES/JE caseload comes from UP, the success of a decrease in overall cases can certainly be attributed to UP.

Taking available evidence into account, it is important to take note of UP’s focus on intensifying communication efforts to enable mass sensitisation about AES/JE. Well-integrated and sustained awareness campaigns by the government have aided much of its fight against encephalitis, which is a strategy that can very well be replicated elsewhere.

The writer works with SPRF, a youth-centric policy think tank focused on social and political research.