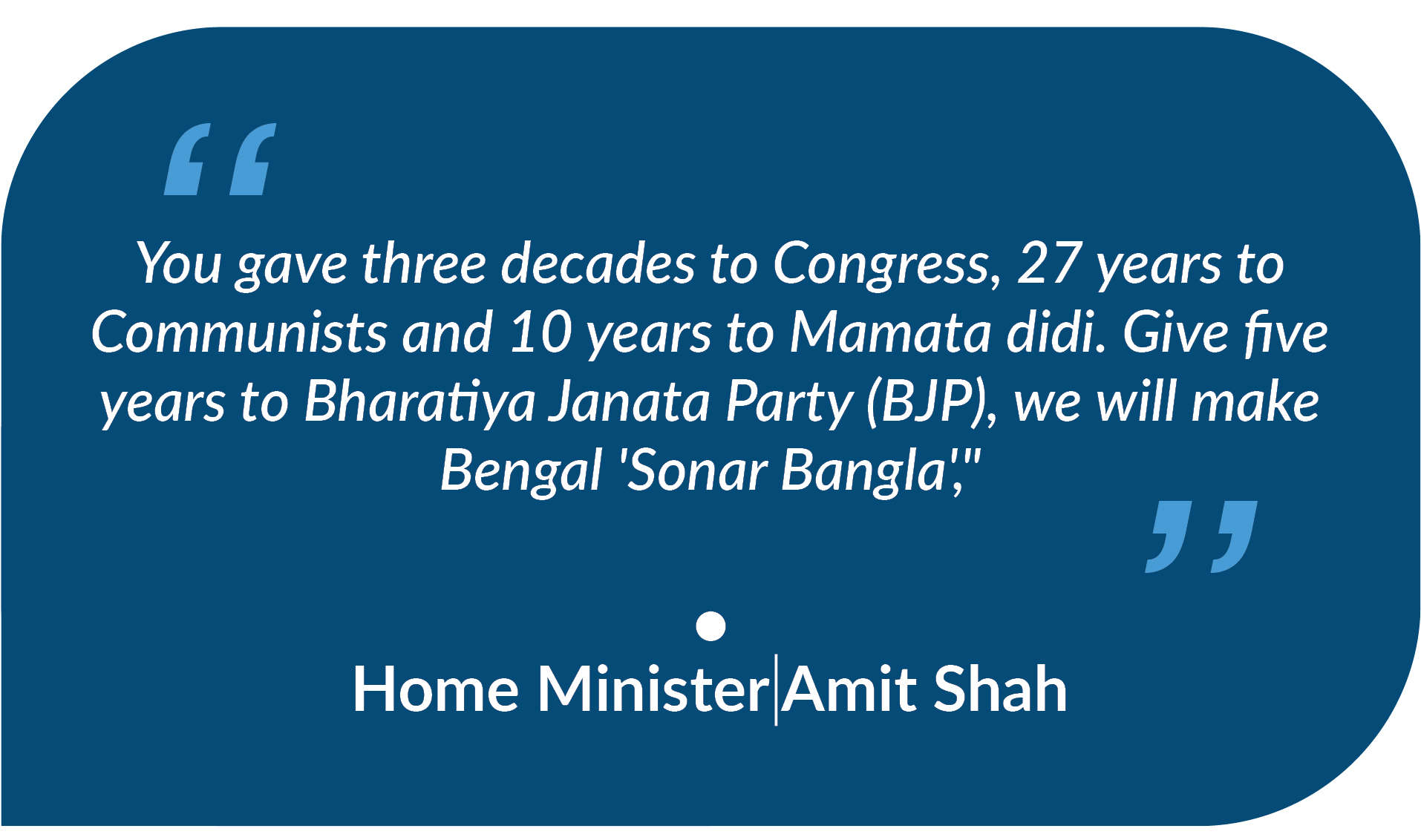

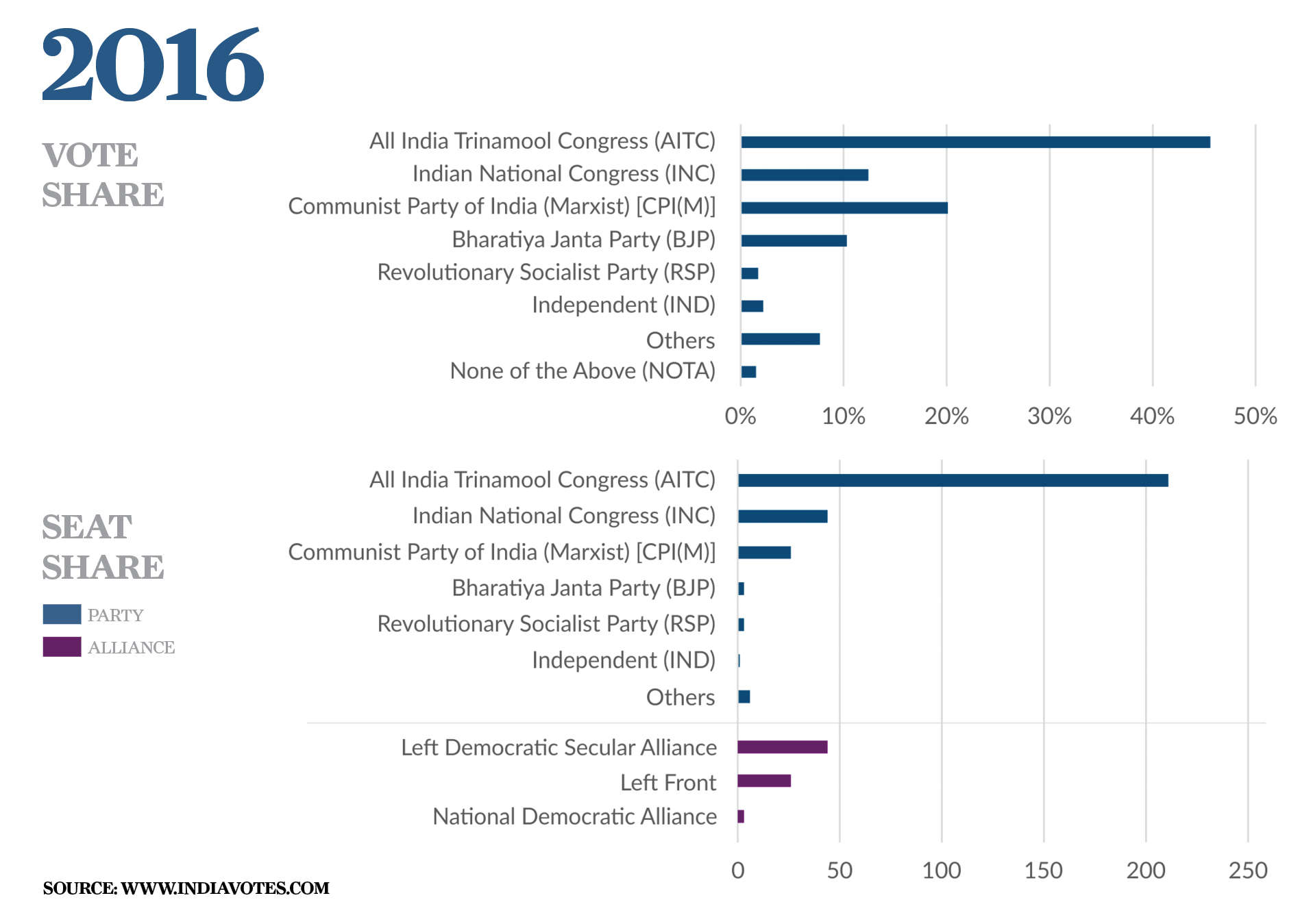

In the past few weeks, All India Trinamool Congress (TMC) supremo Mamata Banerjee and Bharatiya Janata Party Senior leader Amit Shah have been leading roaring rallies across the state of West Bengal. The upcoming West Bengal state elections expected to be held April 2021 are likely to witness a three-way contest in the Assembly elections between the TMC, BJP and the Left Front (in alliance with the Congress).

As the number of COVID-19 cases in India crossed the 10 million mark, the Election Commission has announced that various lessons learnt from the Bihar Assembly Elections will be applied to the West Bengal polls. Sources within the Commission have said that there will be 28,000 more polling booths during the elections to ensure social distancing is observed. Additionally, due to the prominence of electoral violence in the state, the Commission announced that all polling booths could be declared as ‘sensitive’ if warranted by the law and order situation.

Since Independence, the Indian National Congress dominated the politics of West Bengal, until its last term in 1972. The Left Front rose to power from the ashes of the 1972 elections, promising to bring about change and stability. The Left Front ruled the state for 34 years, and political violence continued to be a part of everyday news.

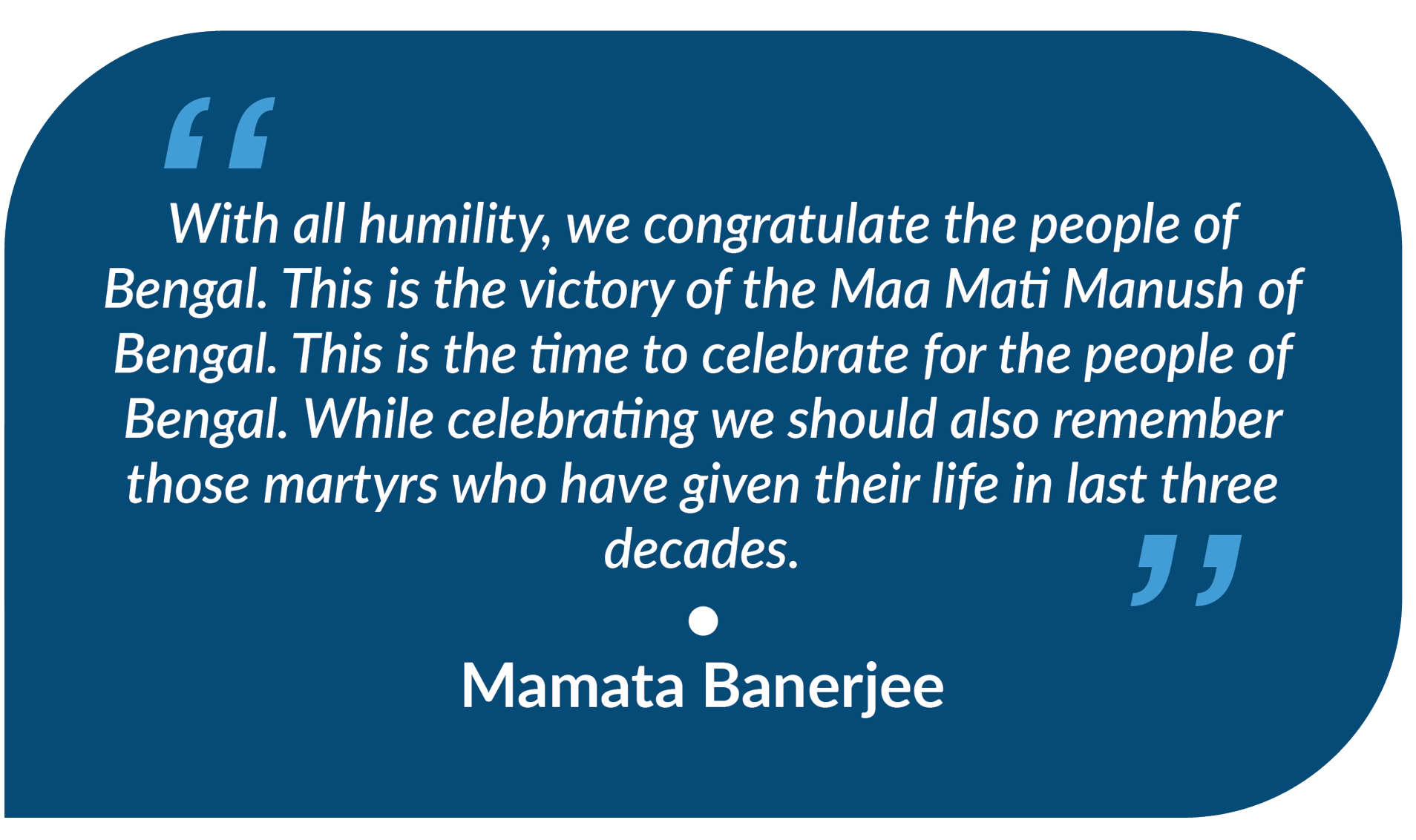

This culminated in the rise and victory of TMC’s Mamta Banerjee, a leader who had started her career with the student wing of the Congress. As the West Bengal polls edge closer, and political analysts and pundits try to predict a winner, let us delve into the various eras of political rule in the state and what they indicate.

1972-1972: THE LAST CONGRESS ERA

For several years after Independence, West Bengal had continued to be ruled by the INC. Although the CPI(M) emerged as the largest party in the state in the 1969 elections, after the Naxalbari uprising in1967 and the subsequent President’s rule declared in 1970, the Congress came back to power in West Bengal for one last time, under the leadership of Siddhartha Shankar Ray.

Scholars and political analysts believe that the trend of using state resources to target opposition parties and members—which has become synonymous with politics in West Bengal—started with Ray’s regime. The 1972 elections were rife with electoral and political violence, and the Congress was accused of rigging the polls.

Ray has been thought to have led the “Hoodlum Years” in West Bengal, where police and Congress Youth Wing members killed both Communists and Naxals. During this period, the then Prime Minister of India, Indira Gandhi also proclaimed a nationwide Emergency in 1975. Academics and historians widely proclaim that the culture of competitive political violence which has now become a well known part of West Bengal politics, started during this period.

1977-2011: LEFT FRONT RULES IN WEST BENGAL

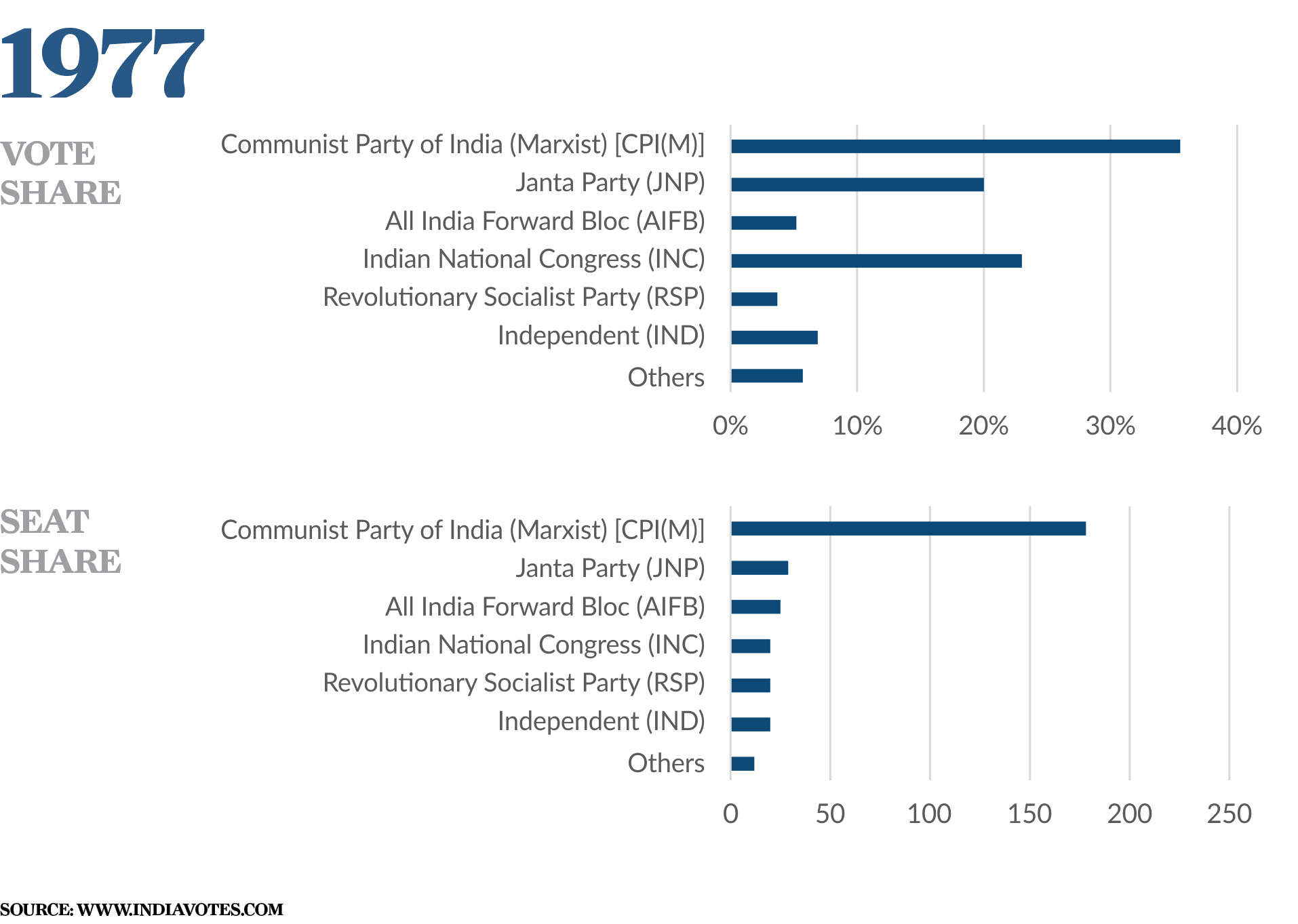

During the 1977 state elections, the Jyoti Basu-led Left Front took control of the state from the Congress, marking an end to over three decades of Congress governance.

The Left Front rose to power with a promise to end the reign of terror prevalent in the previous regime. However, political and electoral violence continued in West Bengal in the 34 years of the Left’s rule.

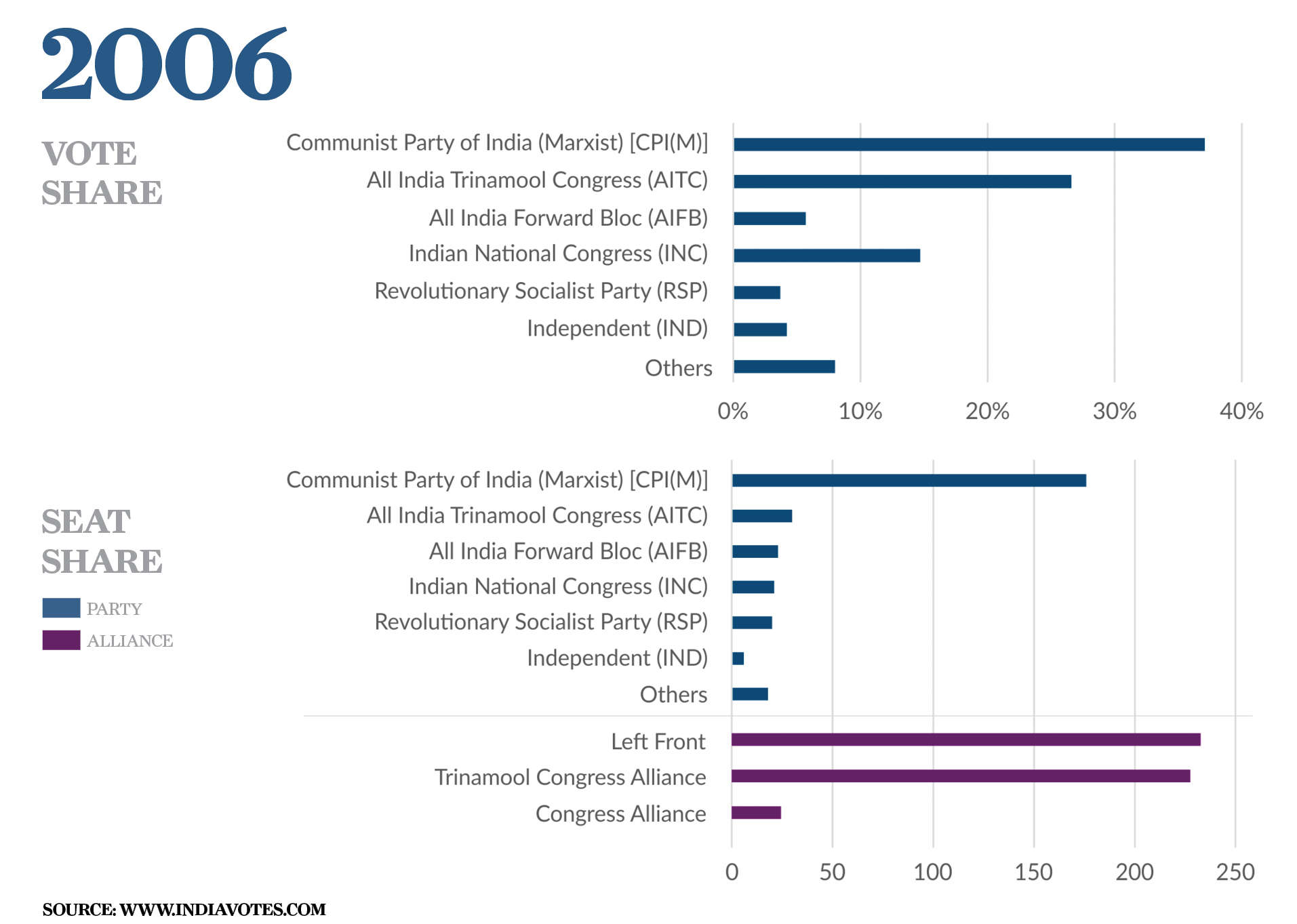

In the 1977 elections, the Left won 243 seats in the Assembly Elections, and the CPI(M) emerged as the largest party in the state.

Other founding parties of the Left Front included the All India Forward Bloc, the Revolutionary Socialist Party, the Marxist Forward Bloc, the Revolutionary Communist Party of India, and the Biplabi Bangla Congress. Soon after coming to power, the CPI(M)-led government launched Operation Barga, which finalised land redistribution.

Along with this, they instituted a Panchayati Raj system in the state — this meant that the party could now exercise power in all of rural Bengal.

THE FORGOTTEN MASSACRE OF MARICHJHAPI

Countless incidents of violence took place in West Bengal in the 34 years the Left was in power. One of the most important incidents was the Marichjhapi massacre in 1979. Just two years after coming to power, the CPI(M) was accused of forcing the eviction of hundreds of Bengali Hindu Dalit refugees who were occupying protected forest land on Marichjhapi, an island in the Sundarbans. The Left Front believed that refugees were a burden to the state, as they were not citizens of West Bengal. Eyewitness accounts from the massacre claim that gunfire by police and Communist workers, blockade and subsequent starvation, and disease, killed thousands (the number of those killed is estimated to be in thousands — no official numbers are available).

MA, MATI, MANUSH: 2011-2020: TMC DOMINATES WEST BENGAL

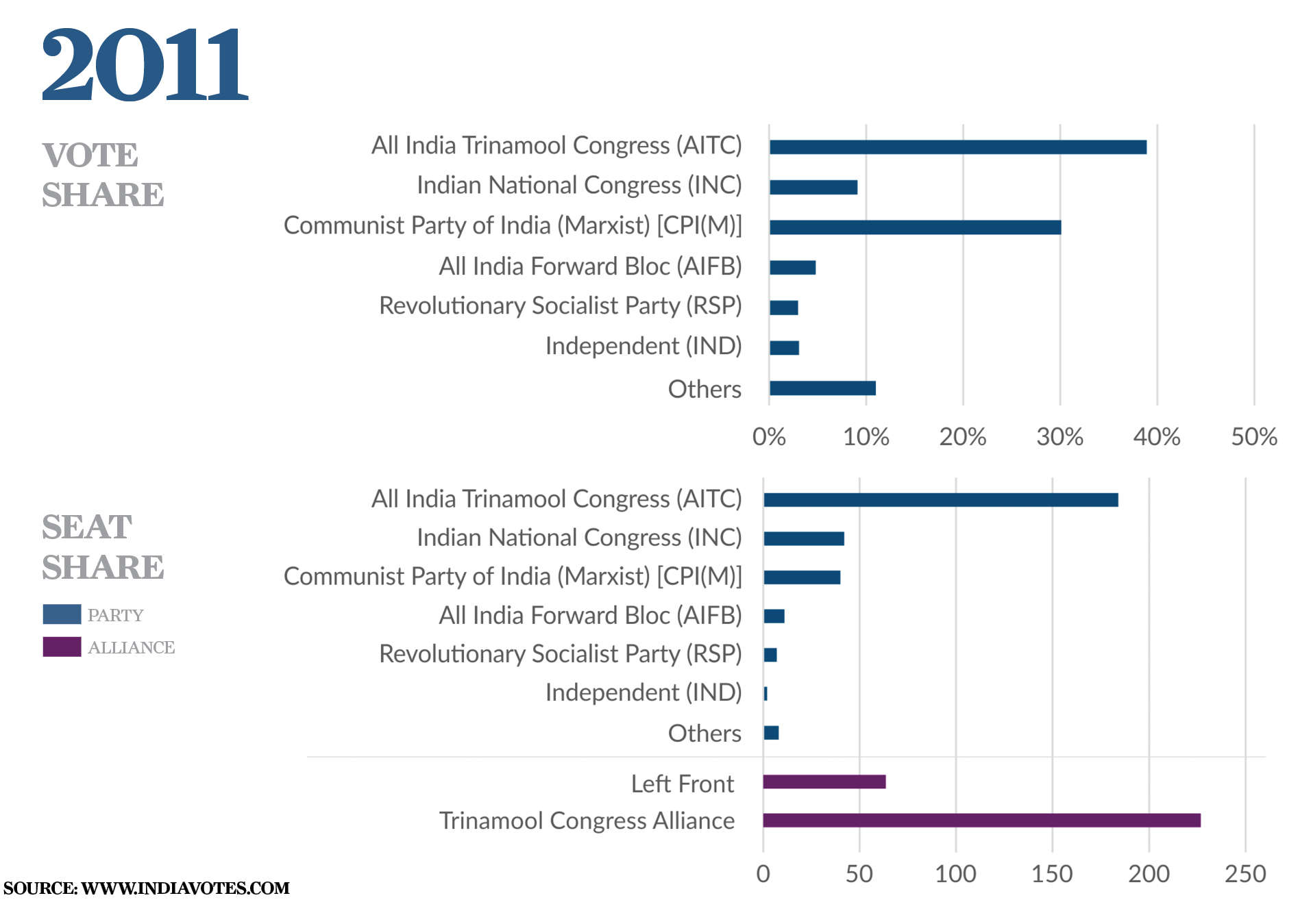

The ultimate demise of the Left Front in Bengal and the subsequent rise of Mamata Banerjee can be attributed to the events of the Nandigram and Singur agitation. In 2007, the Left Front attempted to set up a mega-chemical hub in Nandigram. However, due to a strong movement against this by peasants, the TMC and Maoists, there was violence in the area. Due to police shootings, it is estimated that 14-50 people died in the region.

Similar to the rise of the Left Front in Bengal after the violence in the 1970s, Mamata Banerjee and the TMC promised to bring about “parivartan” in West Bengal in 2011. Using the Nandigram and Singur agitation, and coupling it with widespread anti-incumbency, TMC’s slogan of “Ma, Mati, Manush” (mother, land, people) resonated with the Bengali electorate. Banerjee sold a vision of development to the Bengali people. Clad in a simple cotton sari and her rubber chappals, she became the leader of the state.

She was elected having given a promise to lead the state to stability and non-violence. But the reality begs to differ. The TMC’s regime in West Bengal has so far been far from this. Violent clashes continue between party members and Banerjee has often been criticised by many for being a very “authoritarian” leader.