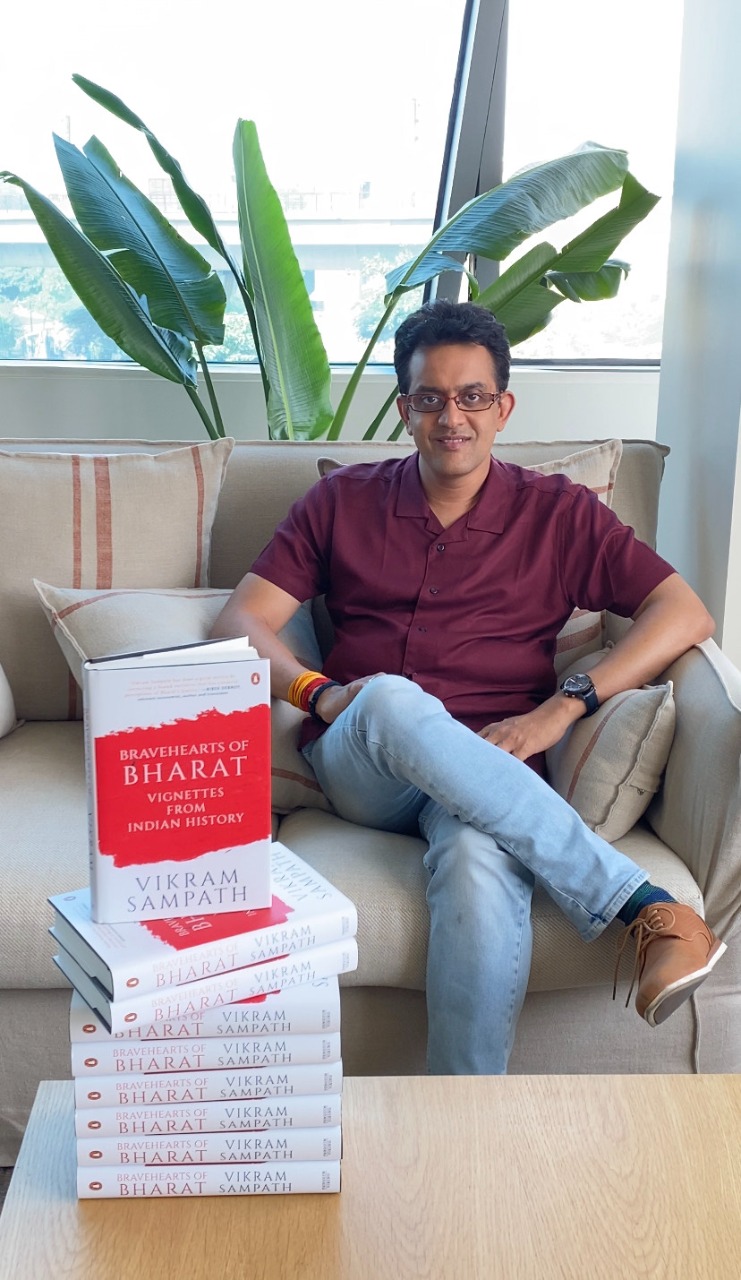

On the launch of his book Bravehearts of Bharat: Vignettes from Indian history, Vikram Sampath, in a free-wheeling interview with The Daily Guardian says the Indian view of looking at history has been looked down upon. Read excerpts.

Q: How different is our Indian history from Bharat’s Itihasa and why do you think today’s India is ready to tell ‘her’ story?

A: A famous shloka that is sometimes attributed to Kalhana postulates that itihasa (literally translating to ‘It Thus Happened’) is one that captures the past in a story form that is inspiring, with a didactic message to society, and that aids in the fulfilment of the four purusharthas of dharma, artha, kama, and moksha. That’s been the Indic view and perspective on history and its utility. Of course, this is quite at odds with the Western model of Leopold von Ranke’s positivist history, which is evidence-based and tangible. There are a lot of fantastic tales, exaggerations, and stories—but the kernel of the truth is also embedded within them, and it is up to the modern researcher to draw out these. The uniquely Indian view of looking at her past has largely been looked down upon over centuries of colonisation and I think we now need to look at our own sources, methodologies and objectives of what history is with an objective and fresh perspective. As that African proverb goes, “Until the lions find their own storytellers, the history of the hunt will continue to glorify the hunter.” India is perhaps now at that stage of her own history when her lions are finally finding their own storytellers.

Q: In your new book, you have covered almost the entire of India, highlighting the regional heroes of which very little is known, post Savarkar’s two volumes why did you choose to club all of them together in one book?

A: My editor at Penguin Random House and dear friend Premanka Goswami conned me into this project by suggesting I do a ‘quickie’ after those exhaustive Savarkar volumes. Little did I realise that this was going to be 15 times tougher as I needed to go into 15 characters, their lives, and stories of which so little is known. But jokes apart, I thought these 15 heroes and heroines were divided by time, space, and geography but united in their undying spirit of courage, valour, resistance, and a civilisational resurgence. Hence, they strung together easily, and I thought that it was the best way to put them all together in one volume. Given the tremendous response the book is receiving from across India, there have been lots of demands for a sequel that covers more such unsung bravehearts from other parts of the country not represented in this volume.

Q: You have highlighted quite a few women warriors and heroes in the book right from Rani Naiki Devi of Gujarat to Rani Abbakka Chowta, Chand Bibi to Devi Ahilya Bai that also gives a sense of not only the contribution of women in our wars of thousands of years but also in some way makes one feel how we let them down and how did we end up getting a reputation of being a patriarchal society?

A: It is tough to put these labels of ‘patriarchy’ etc. that are very modern constructs. Rani Rudrama Devi’s father, Ganapatideva of the Kakatiya dynasty, groomed his daughter to be a warrior and his successor right from her childhood. Rani VeluNachiyar’s father taught her all aspects of warfare and multiple languages like French, Urdu, and English. Rani Ahilya Bai Holkar’s father-in-law, Malhar Rao Holkar, provided education to his daughter-in-law, discussed matters of state with her, trusted her more than his own son, and even prevented her from committing sati when his son died. These were the patriarchs too–fathers and fathers-in-law who let their daughters thrive and flourish. But you are right that our history has been unfair to these women and their contributions. Women in positions of power were seen with suspicion. Rani Didda of Kashmir or Rani Abbakka of Ullal are always being accused with insinuations of doing black magic to eliminate their own children, and so on. Even the contemporary chroniclers of Rani Naiki Devi of Gujarat hardly mention or credit her for her stellar success in defeating Mohammad Ghori in 1178. So I think it is a mixed bag somewhere.

4) We are celebrating the birth anniversary of Lachit Barphukan, one of the very few of the several other heroes who have now been brought into mainstream conversations, tell us more about the kind of research that went into unravelling his story.

A: Lachit Barphukan’s was a fascinating discovery for me, as I knew next to nothing about him when I started off. Quite contrary to the common perception that India and Indians hardly documented their history, we find the converse true- the documented history of Kashmir by Kalhana, the meticulous chronicles of the Cholas in multiple sources like coins, temple inscriptions, palm leaf manuscripts etc. and in Assam where from the 4th Century BCE people maintained accounts that were later perfected under the Ahoms in documents called Buranjis. Yet if we don’t know this history, it is because they were kept away from us. I relied on a lot of regional literature for this book, and in Assam’s case, on the Buranjis. Lachit’s story is also indicative of how Kamrupa (Assam) remained invincible to imperialist designs for several centuries, be they Afghan or Mughal invaders. Even Bakhtiyar Khilji, who had ransacked our grand universities in Nalanda and Vikramshila, was beaten back by King Prithu of Assam in 1206. Right from 1615, Mughal incursions into Assam were thwarted. It was a brief occupation after Mir Jumla’s conquest in 1662. But barely a decade later, the Ahoms regrouped themselves, built their army from scratch and as the typical underdogs against the mighty imperial Mughal army, the native army managed under Lachit as commander flushed the Mughals out totally in the Battle of Saraighat in 1671. The manner in which the Ahoms managed this feat is something that should be taught in every school and college, and perhaps every B-school, in strategy lessons. But here we are in this country, where the majority of the people may not even have heard of who Lachit was or what this episode in our history was all about. Not the people’s fault, it is that of the historians writing our stories hitherto, who kept these inspiring tales away from common knowledge.

5) Which of the heroes covered were the most difficult to get more literature and evidence on and how does a historiographer remove folklore from reality in cases where there is very little known?

A: Each of them had their own challenges, as there’s so little or scattered information on many of them. Naiki Devi, for instance, is a barely discernible ghost in the annals of our history. Rajarshi Bhagyachandra Jai Singh of Manipur was tough to reconstruct as there was so little that I could lay my hands on. In Abbakka’s case, where I even saw practices like the Bhoota Aradhane where she is invoked, it is a tenuous balance that a modern historian needs to traverse as to how much of the folklore and oral narratives one takes and how much one leaves behind. Triangulation with scanty and extant records is a small way to ensure some modicum of accuracy. More than anything, a true researcher of history, in my view, is someone who is humbled by the fact that the sources that she/he refers to are scanty, compromised, incomplete, or biased.

As told to Lipika Bhushan, a columnist and senior publishing professional. She is the founder of MarketMyBook.