Come, fill the Cup, and in the Fire of Spring

The Winter Garment of Repentance fling:

The Bird of Time has but a little way

To fly — and Lo! the Bird is on the Wing.

— Omar Khayyam (1048CE-1141CE)

Long ago, Omar Khayyam wrote poetry that was sensuous and inclusive. He was born in Iran — Khorasan — more than a thousand years ago. His poetry showcases a culture where mosques existed in peace with wine, women and song. And yet today, when we see the state of women in Iran or Afghanistan, we feel sorry for the repression they face.

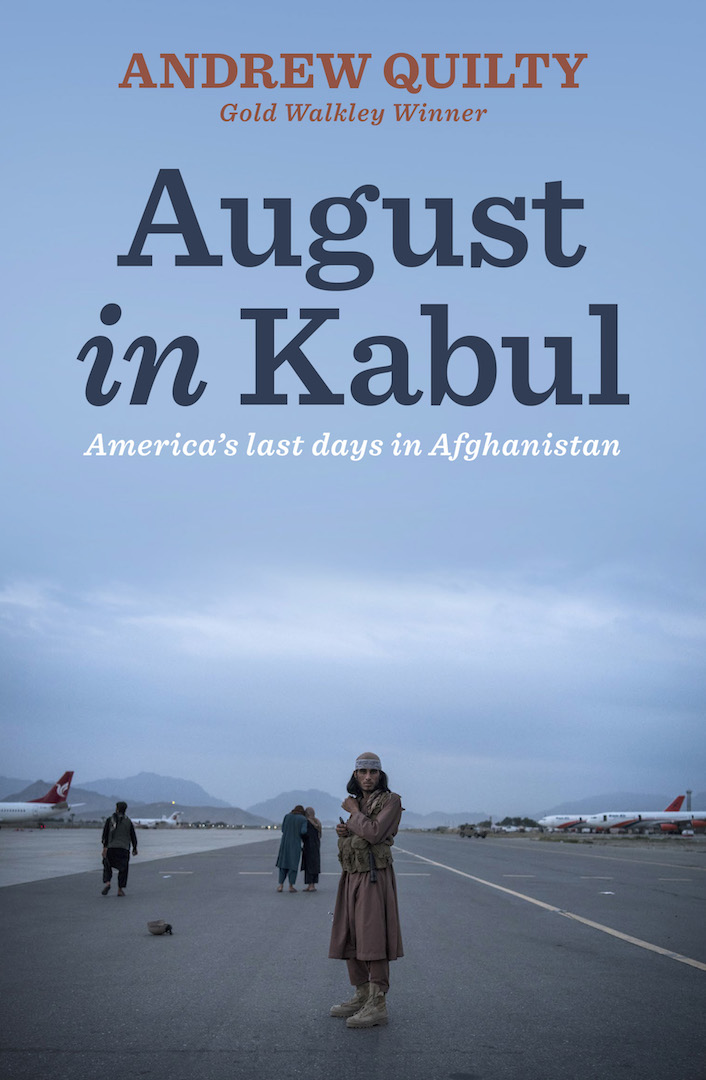

In a recent book,August in Kabul:America’sLast Days in Afghanistan and the Return of the Taliban, the author, award-winning journalist Andrew Quilty, highlighted the dilemma of Afghan women, who even in pre-Taliban days, faced oppression. He wrote: “Preserving the safety of women is a common sleight of hand used by Afghan men to keep those within their family under control. Neglecting such a duty and allowing a young woman the freedom to walk when they wish in the streets, to socialise with unrelated men, and to develop their understanding of the world outside the home and their ideas about their place therein, is deduced by many outside the immediate family to imply the woman is what Nadia refers to euphemistically as a ‘bad girl’. Boiled down, a ‘bad girl’ is one who cavorts and sleeps with men out of wedlock—a prostitute in Afghan terms, a great stain on a family’s honour. To avert such a possibility, rather than confront those who deliberately misinterpret the young woman’s ways and use it to undermine her family, instead, her brothers, father and male members of the extended family more often elect to restrain her behaviour.”

Nadia was a free-spirited student who was rescued from such familial abuse by a foreign social worker and survived, unlike, Najma, a journalist and YouTuber, who died in a blast caused by a suicide bomber outside the Afghan airport as she waited to leave. The bomber had been freed from a prison by the victorious forces of Taliban who had just taken over Kabul around the Independence Day of India, two years ago. Quilty brings these stories to us with compassion and recreates the terror brought in with the gun-wielding Taliban who rule the country now.

He tells us how the Taliban evolved out of the Mujahedin. They were students who had been enabled to protest against the communism of Soviets that laid desolate Afghan hillsides with chemical warfare. From students, the Mujahedin grew into perpetrators of violence and violators of men and women who disagreed with their agenda. And yet, now they have been accepted as rulers of a whole country. The book leaves us wondering, even if we criticise their stance on women or openness, do we, or for that matter, any superpower have the courage to make a change? Also, it leads to the realisation that when we mouth tradition for any unjustified social codes that repress and cannot be erased by simply instituting rules of law — be it dowry, sati, violence against women, child marriage or even restrictive dress or food codes — are we being any different from bullies or terror mongers?