Jawaharlal Nehru had witnessed it all. The bloody Partition, the canal disputes, the exchange of letters with Lilienthal and Black, the droughts of 1957-58 that saw agriculture losses in India as high as 50 per cent, the long years of water negotiations and the uncomfortable task of having to deal with the seven prime ministers in Pakistan who were sacked from 1947 to 1958.

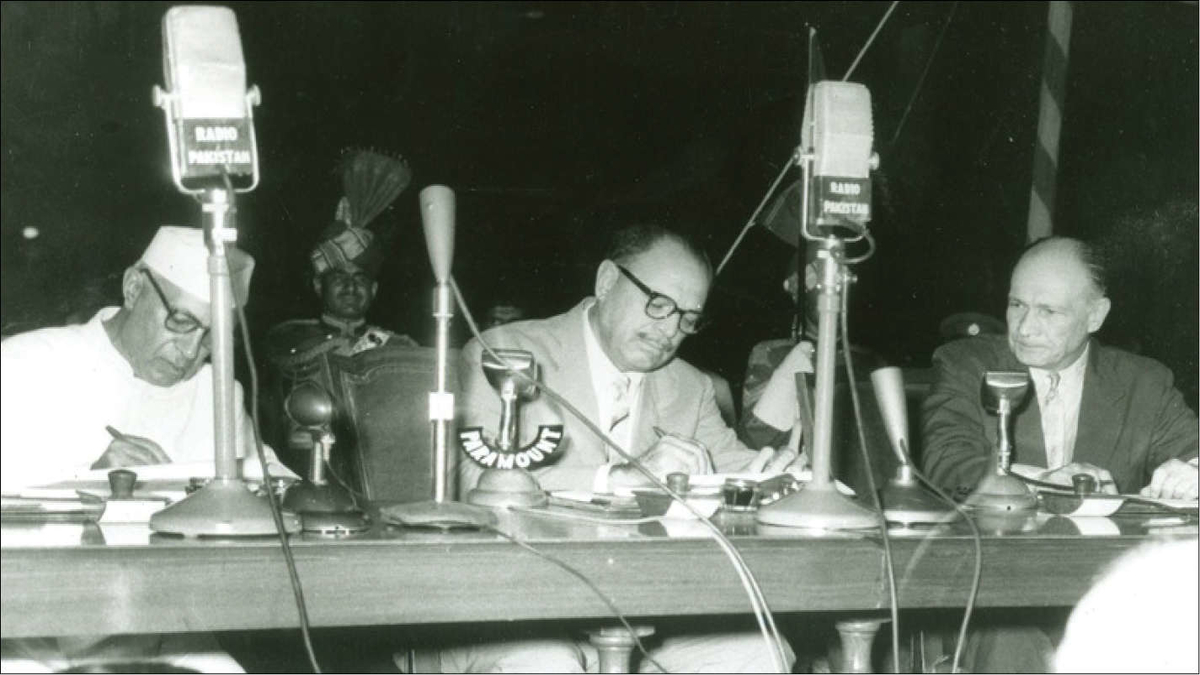

As fate presented, Nehru, a model of democratic leadership, had to sign the Indus treaty with Ayub Khan, Pakistan’s first military dictator. There could not be a greater irony. But now, in front of the House, Nehru had to respond to the sentiments of the Opposition as well as some of his party members in what probably was one of his biggest defences, on an issue which had bedevilled him for long. Some of his cabinet members had expressed strong reservations over the financial and strategic implications of the treaty. These included the incorruptible and the very austere finance minister Morarji Desai and Krishna Menon, the defence minister, who was being disparagingly referred to as “India’s Rasputin”.

After having patiently listened for almost two hours to the speeches of the members, Nehru rose to speak on the fateful day on 30 November 1960. As the leader of the House, exhilarated as he always was on such occasions, Nehru began a shade aggressively by expressing his disappointment over the members’ view on the issue.

A host of critical questions had been put forward by the House broadly signifying India’s foolhardy generosity, its unnecessary commitments and inability to settle the Partition debts. Concerns over the Kashmir issue, dispute regarding the Rann of Kutch, status of “Azad Kashmir” where the Mangla dam was being constructed by Pakistan while India’s proposal to build a dam over Chenab was put on hold owing to Pakistan’s insidious pressure, were ventilated by the members with a full sense of their responsibility. Nehru had his plate full, had made notes while carefully listening to the speakers and with “passion but not with malice” set about answering it.

Nehru agreed that the events since the canal dispute of 1948 had not been a pleasant period and one of great frustration, but in the same breath humbly submitted that “it is a good treaty for India and I have no doubt about it in my mind”. While assuring the House that close attention was paid to each detail, he tactfully praised the engineers who fought for India’s interest strenuously. As the prime minister, “I got only the broad facts,” noted Nehru and the engineers were the “experts in this matter”.

He came back to the canal dispute explaining that the time and circumstances then were radically different, “It was not a detailed examination; it was a broad approach. I regret to say that that approach was not followed later by the other side, as it often happens”.

The role of the World Bank was a less controversial issue to respond to, given that the House was not categorically vehement about the World Bank’s role except for some pointed observations by (Odia writer Surendra) Mahanty.

For Nehru, the World Bank’s engagement in the negotiations was an ‘ordinary thing to happen’, least of all alarming; “they were not becoming arbitrators or anything”.

Recalling his conversations with Lilienthal and Black on the active support of the World Bank, Nehru said, “It was only a question of an attempt, if you like, at the most, to help in our coming to an agreement between ourselves. They could not impose anything.”

From his disappointment on what he felt was the ‘narrow mindedness’ of the House on the treaty to his explanation of the circumstances of history and the complexities of the issue, Nehru enlightened the House on the question of consulting Parliament. “Are we to come at every step and ask Parliament?”

Allowing the rhetorical question to seep in, he then elaborated, “Very wisely, the Constitution and convention lay down that in such agreements, Government has to stake its own judgement, its future, on it. There is no other way. One takes a risk; maybe that Government may go wrong. But there is no [o]ther way to deal with it.”

However skilfully Nehru tried to separate himself as the carrier of a ‘broad perspective’ from the nitty-gritty of the negotiations that the engineers engaged in, there was an undeniable Nehruvian internationalist mindset to the entire water issue with Pakistan. Nehru’s interest in international problems was well known. His ideals of oneness, though, clashed with the realities of power politics and interest-oriented relations which he understood but adamantly refused to accept. More than a decade ago, he had hoped for an emergence of Asia as an influence on world peace, which soon fell apart.

Later, his famous enunciation at the Bandung Conference in 1955 that laid the foundation for the Non-Aligned Movement, “let us not align ourselves but have a line of our own”, was immediately contradicted by the creation of two military pacts, the SEATO and the Baghdad Pact (later CENTO). On the Indus treaty, having heard the diatribes, he asked the House, “Is that the way to approach an international question?”

And in a pedantic tone expressed, “Something is done because it is considered, in the balance, that is desirable… In such matters there has to be give and take.”

Nehru did regret the fact that the negotiations were long-drawn and that he had anticipated a year at best to reach a settlement. But there was no remorse in stating, “We purchased a settlement, if you like; we purchased peace and it is good for both countries.”

Nehru excused himself from the House as he had to accompany the crown prince and crown princess of Japan who were on a visit to India, but not before he clarified the issue of consultation with the state governments on the negotiations, “Whenever any proposals were put before me, I asked the Commonwealth Secretary [M.J. Desai] . . . Only when he said ‘Yes’, did I look into it… It may be that what the Commonwealth Secretary reported to me was due to some misunderstanding. He thought that they agreed when they had not.”

It is a pity that Nehru did not stay on for the entire length of the debate as Vajpayee raised an important question on the Indus Commission. He cited Ayub, who soon after the treaty was signed had said, “By accepting the procedure for joint inspection of the river courses, India has, by implication, conceded the principle of joint control extending to the upper region of Chenab and Jhelum, and joint control comprehends joint possession.”

The excerpt is from the book ‘Indus Basin Uninterrupted’ (published by Penguin Random House).