A journey starting from the picturesque East Sri-Lankan coast and culminating in the blue mountains of South India traversing through the exotic Malabar Coast might be the perfect getaway for an intrepid traveller. But this piece is not a travelogue; it is, instead, the trajectory of Indian Navy towards the goal of self-reliance, of making in India and of being a pioneer in Atma Nirbhar Bharat.

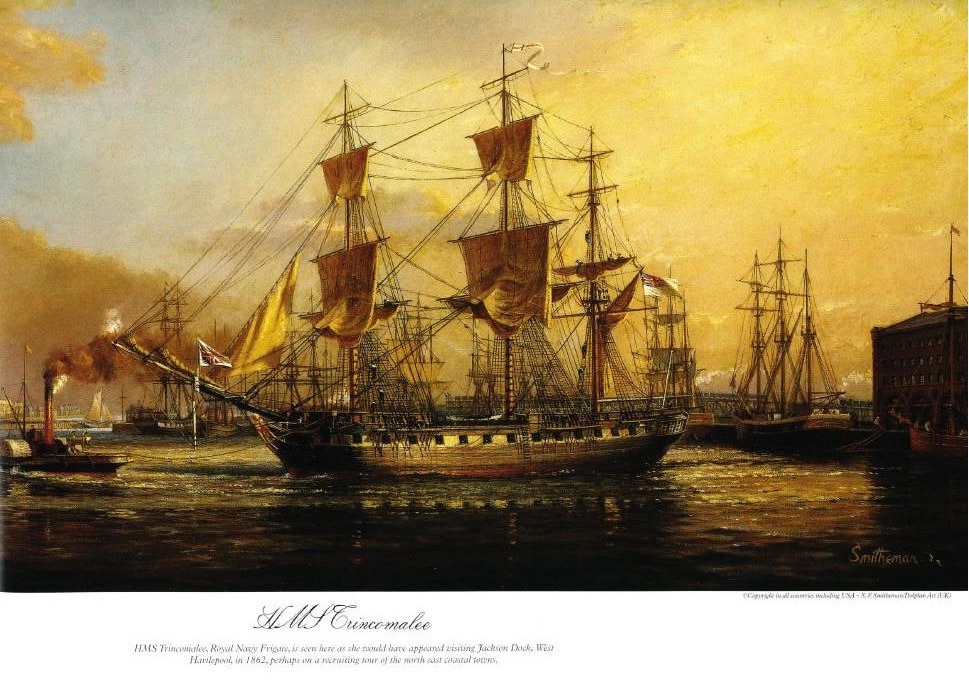

It’s a journey in which 12 Oct is a most significant date in Indian Maritime History. It was on this day more than 200 years ago, in 1817, that HMS Trincomalee – a Leda class 46 gun fifth rate frigate displacing 1447 tons – was launched. Notwithstanding the fact that she was named after a Sri Lankan port and served under a British flag, she was built in our own Naval Dockyard at Mumbai and is afloat even today, berthed in Hartlepool, UK, as a museum ship. In short, the second oldest ship in the world was made in India. And despite many changes over all these years, almost two thirds of her hull is still Indian teak. The mind boggles that a Frigate of the Napoleonic era is still in mint condition. Maritime historian Capt Ramesh Babu (Retd), the author of a book on Trincomalee (published by the Navy), who visited the ship few years ago, after her restoration, writes “stepping on board the ship is an exhilarating experience, especially if you have served in Bombay dockyard”.

Trincomalee’s bicentenary plus story is shining testimony of India’s maritime prowess and shipbuilding skills, alas unknown to many in our country. It is true that from about the 13th century onwards India declined as a maritime power and as a seafaring nation. This was to lead to the denouement of colonization with its attendant collateral damages. Loss of supremacy at sea led to loss of sovereignty on land. All this is well known, even if not completely understood, by Indians at large.

However, even in this bleak period there were some bright patches or rays of hope. The heroism and maritime savvy exhibited by the Admiral Queen Rani Abbakka of Ullal, the Kunjali Marrakars of Malabar and, later, by the Marathas is stuff of legend. Our coastal and riverine navigation and commerce continued. And the performance of our ships and naval personnel in both world wars earned kudos. Indian shipbuilding too survived and thrived in the colonial and precolonial period with several parts of India such as Bengal, Kashmir, Lahore, Surat, Bassein, Dabhol, Goa Calicut and, even, possibly, Bombay being among the important ship building centres. As naval historian Rear Admiral Satyindra Singh says of the Mughal period “there is evidence available to establish the high standard of technology in the construction of these ships and craft”. Ramesh Babu adds “Building of seagoing vessels would have existed in and around Bombay right from antiquity”. Here, it is necessary to emphasise that building a ship is the very acme of engineering, design, ergonomics, architecture and several other disciplines. Building warships is even more complicated business given the huge interplay of several complex factors.

In this light, therefore, one of the most illustrious maritime achievements of the colonial times would be that of the Wadia shipbuilders and the Bombay docks. The British, some years after moving their Headquarter from Surat to Bombay, built the Dock in 1735 and persuaded the Master Shipbuilder Lowejee Nusserwanjee Wadia to shift base in 1736. The rest, as they say, is history. Interestingly, renowned maritime historian Cdr Mohan Narayan (Retd) believes that the dock, in some form, and ship building happened even before 1735 but that would be another area of research.

The Wadia (carpenter or shipbuilder) family was known for their high standards of workmanship. With the backing of their masters and an enabling environment in Bombay, the Wadia clan rolled out ships of different types – Pattimar, Grab, Galbat, Snow, Brigantine, Sloop, Schooner, Clipper, Frigate, Ships of the Line – as though in an assembly line. Between 1735 and 1899, seven generations of the Wadias built a staggering 363 ships of the finest quality and class. That is a stupendous average of more than 2 ships per year. Over a century and half, these ships built in India, by Indians, for the British and others, sailed all over the world, earning their spurs in war and peace.

They also made history. Apart from the aforementioned Trincomalee – often described as the ship that sailed through time – built under the supervision of Jamsetjee Bomanjee, it also included ships like HMS Minden (on which Francis Key wrote the ‘Star Spangled Banner’, the American national anthem), HMS Cornwallis (on which the Treaty of Nanking was signed, which, among other things, ceded Hong Kong to the British), HMS Asia (which took part in the Battle of Novarino, the last battle totally under sail) and HMS Ganges (the last Flagship of Royal Navy under sails). Ramesh Babu brings out that “Jamsetjee built world class battleships, frigates, grabs and other vessels for the Royal Navy using local carpenters and traditional skills at these new facilities”. This is true of other Wadias too.

Incidentally, the above mentioned Bombay Dock, the oldest in Asia, is functioning even today as the Naval Dockyard and is the principal yard that maintains and refits navy ships. The northern part of the erstwhile Bombay dock is today’s Mazagon Dock, India’s premier ship building centre. Together, these two are a splendid account of history, technology, human spirit and their link with the city but that needs a separate telling.

Many thinkers and historians opine that there is not much to celebrate these achievements since they were essentially in the service of the British crown, a foreign ruler. They make a fair point. But I believe that we must acknowledge the technical prowess, the skills and the overall ecosystem that enabled such world class ships to be built barely two to three centuries ago. More importantly, they underscore our maritime and shipbuilding skills honed over centuries and the inherent DNA, which ‘like the soul long suppressed found utterance’, to quote Pandit Nehru in another context, in this endeavour. Maritime historian and author Cmde Sanjay Kris Tewari (Retd) emphasises this aspect when he says that ‘we must not forget the contribution of one of the most important components in maintaining and sustaining a Navy viz. the dockyard. The Yard at Bombay was a pivotal institution in the sustenance of the British Empire, manned and operated almost entirely by our people. The Yard has also played a central role in the growth of our Navy. We still operate the dry docks that were built during the time of Lowjee Nusserwanjee”.

It was the combination of many circumstances that led to the decline of this flourishing industry. The steamships that replaced sail changed the whole paradigm of seafaring, for one. The opening of Suez Canal which was difficult for sail ships to navigate made their existence more difficult. And, above all, a concerted effort by the British to keep India at a low industrial and military (especially naval) threshold left us in the cold as new and powerful ships came to be built in the new steam and industrial age.

In an article written for this newspaper on 02 Oct, (https://thedailyguardian.com/on-mahatmas-birthday-remembering-indian-navys-pre-independence-journey/), I brought out how the establishment of the Royal Indian Navy (RIN) and the World War 2 brought back some urgency in building and refitting ships in India as the war effort needed many more ships. By Jun 1941 as many as 263 merchant and naval ships were fitted with degaussing equipment made in India, to counter the mine threat. July 1941 marks another landmark moment in Indian ship building when the first Basset class trawler HMIS Travancore, built at Kolkota, was commissioned. In the next two years 11 more ships were commissioned. Bangor class minesweepers also built in India joined RIN 1943 onwards. Several smaller craft and harbour defence boats were also locally built.

Thus, after independence, it was the above mentioned shipbuilding DNA that came to the fore as our Navy set out to create a self-reliant force. The Navy’s founding fathers realised that we could not build a great Fleet by being a buyer’s Navy – it could be done only by building our own ships. As Rear Admiral Satyindra Singh in his book ‘Under Two Ensigns’ brings out, “As far back as 1949, it was realised by Vice Admiral Sir Edward Parry, the then Commander-in-Chief of the RIN, that any Service that depended entirely on imported ships, equipment and expertise would rue the day the umbilical cord of vital supplies from abroad was severed. It was he who during the late forties, had decided to set up a naval research and development organisation in India so that it could help the Navy to progressively indigenise the production of naval hardware and develop the necessary expertise within the country”.

Accordingly, a 1948 plan document of the Indian Navy envisioned aircraft carriers and submarines when we had less than half a dozen sloops. Many may have described such dreams as fantasy or whimsy. There were other factors disadvantageous to the fledgling Indian Navy – from low technology base to funding constraints, from the landward orientation of our leadership to an Army and Air Force that threatened to grab the lion’s share of resources. Hence, we adopted a two pronged approach. While initially buying from abroad, we set up our own design bureau to design ships suited to us. Our shipyards and dockyards slowly played ball.

We began with a small patrol craft INS Ajay built at the Garden reach Shipyard, Kolkota, moved on to a survey ship INS Darshak in 1964, the Bhatkal class minesweepers in 1968, started work on the first Leander, the Nilgiri class, in 1965 which were commissioned 1972 onwards, and worked our way up through the Godavari class frigates, the Khukri class corvettes, the Brahmaputra class frigates, the Delhi class destroyers, the Shivalik class stealth frigates, the Kolkota class destroyers besides other lines such as Landing Ships, Offshore Patrol Vessels, Missile boats, Survey ships, ASW corvettes, Auxiliary vessels, Coastal and Harbour defence craft and so on Thus, to cut a long story short, today, 70 years after independence, we are building our own ships and submarines, including aircraft carriers and nuclear submarines. And our entire team of designers, builders, integrators, overseers and users are forming a virtuous circle each reinforcing the other.

To be sure, we still have some way to go. We need to have nearly 100 percent indigenisation; we need weapons and many systems to be sourced from within. But every ship that gets constructed has more indigenous content than her predecessor, every ship an improvement over the previous one. So much so that today a navy ship constructed in India is no longer news. And we also need to look at the context. Let’s not forget that India designed her first indigenous car, the ‘Indica’ in 1997 much after we had built our first ship. Incidentally, in 1997, India had built the most advanced destroyer, the INS Delhi, which was the 75th warship built in India and catapulted Navy into a new era.

Today, India builds world class warships designed by Indian Navy engineers and scientists. Even as I write this, the Indian Navy has quietly added to its amphibious Fleet this year, the Visakhapatnam class of destroyers are nearing completion, the Aircraft carrier at Kochi is conducting harbour trials and, illustrating the spin offs and virtuous circle, the private sector firm Larsen and Toubro (L and T) has delivered 7 Offshore Patrol Vessels (OPVs) to the Indian Coast Guard, five of them ahead of schedule.

It has been a monumental journey and nothing symbolises this more than the happenings of 28 Sep 19, when three interrelated events took place in Mumbai. These were the commissioning of INS Khanderi, the second of the new Kalvari class submarines, the launch of the new Nilgiri class stealth frigates, the next generation multipurpose platforms that would enter the service from 2022 onwards (the 75th year of our independence) and inauguration of the Aircraft Carrier dock.

There are multiple significances to the three events – all with the Raksha Mantri Shri Rajnath Singh as the Chief Guest – when viewed holistically. They talk of our prowess in indigenisation, they attest to our three dimensional virtuosity and to our long legacy of aviation and submarining proficiency, The Aircraft carrier dock is an engineering marvel (do google for details) steered by Navy’s technical professionals. Fittingly, this dock was built by HCCL (Hindustan Construction Company Limited) one of India’s leading Engineering companies. HCCL was founded by the great visionary and freedom fighter Walchand Hirachand, who is also a maritime hero.

INS Khanderi along with its sister ship INS Kalvari heralded a new dawn for us as they entered naval service. Unlike their earlier avataars, the Foxtrot class submarines which were bought from erstwhile Soviet Union, these have been built in India, at the Mazagon Dock. It is true that this is a French Scorpene design and most of its components are French, but the mere fact of building a boat (as submarines are called) in India is bound to unleash several energies that would aid our manufacturing and entrepreneurship. Interestingly, they are the first Indian Naval vessel to be built using a modular approach, whereby five separate sections were welded into one or booted together.

Building submarines will be the final frontier to conquer in our indigenous programme. Ironically, we had started building conventional submarines thirty years ago, in the eighties with the SSK programme. Built to German HDW design, the last two boats were constructed, also at Mazagon Dock, with the fond hope that this would ultimately lead to our own fully indigenous submarine building line. Alas, it was not to be and the lost decade of nineties dissipated our entrepreneurial energies. All the technical competence that we had built withered away and the envisioned assembly line vanished. Hopefully, we have learnt our lessons and will make sure that this does not happen again.

The rebirth of the Nilgiri class will strike a chord with most navy persons. A previous article of this author on 15 Aug on Adm AK Chatterji (https://thedailyguardian.com/remembering-the-admiral-who-shed-his-vice-and-built-the-navy/) brought out how events in 1968 culminating with the launch of the Nilgiri class frigates, our first major warship programme marked a watershed moment in our ship building history. After the last of this class were decommissioned in the early years of this decade, there was a fond hope that they would be reborn. The Navy’s decision to christen the latest new generation guided missile stealth destroyers as the Nilgiri class could not have come at a more opportune time emphasising Navy’s tryst with transformation while being rooted in tradition.

These events happened in Naval Dockyard and Mazagon dock, the very places in Mumbai where maritime history has been repeatedly made. As maritime historian and corporate trainer Cdr Ninad Phatarphekar (Retd) emphasizes “Hidden away in the history books is the fact that from 1736 to 1932 over 400 ships and vessels of various descriptions were built at Bombay Dockyard. Added to that are some 220 odd ships and vessels built by Mazagon Dock Shipbuilders Ltd. from 1960 onwards taking the total to well over 600 ships and vessels which is a singular achievement for any city or shipyard. Shipbuilding and Ship repair is an industry that has flourished in the city of Mumbai for close to three centuries”.

The Indian Navy has been a pioneer in ‘Make in India’. Our naval planners and thinkers and designers and scientists and overseers have never wavered in our quest for blue water multi domain capability through self-reliance. The Navy’s technology ecosystem needs another article in itself to bring out the magnitude, depth, scope and the vast array of its achievements. (Do watch this space for more in the forthcoming weeks). For the moment though, we can proudly say that we have a legacy of 200 years of Making in India – though it is actually much more than that depending on your historical outlook. The commemoration of Trincomalee, recollection of Tranavancore and rebirth of the Nilgiri class gives us much cause to be proud of our past, celebrate our present and be optimistic about the future. Hopefully the rest of India will relish and cherish these maritime milestones. To borrow a phrase of a respected senior “Samudra Bharat hi Samrudhha Bharat hai” or “Only a Maritime India can make a Prosperous India’.