The politically dramatic entry of N. Chandrababu Naidu as chief minister in 1995 proved to be equally dramatic for the fledgling technology sector in Hyderabad making the then united Andhra capital ‘beat Bangalore in information technology.’ This was the time; Karnataka government had already roped in the Tata group and a consortium of Singapore-based companies to form the Information Technology Park Limited in Whitefield as the second technology enclave. Hyderabad did not have such an enclave.

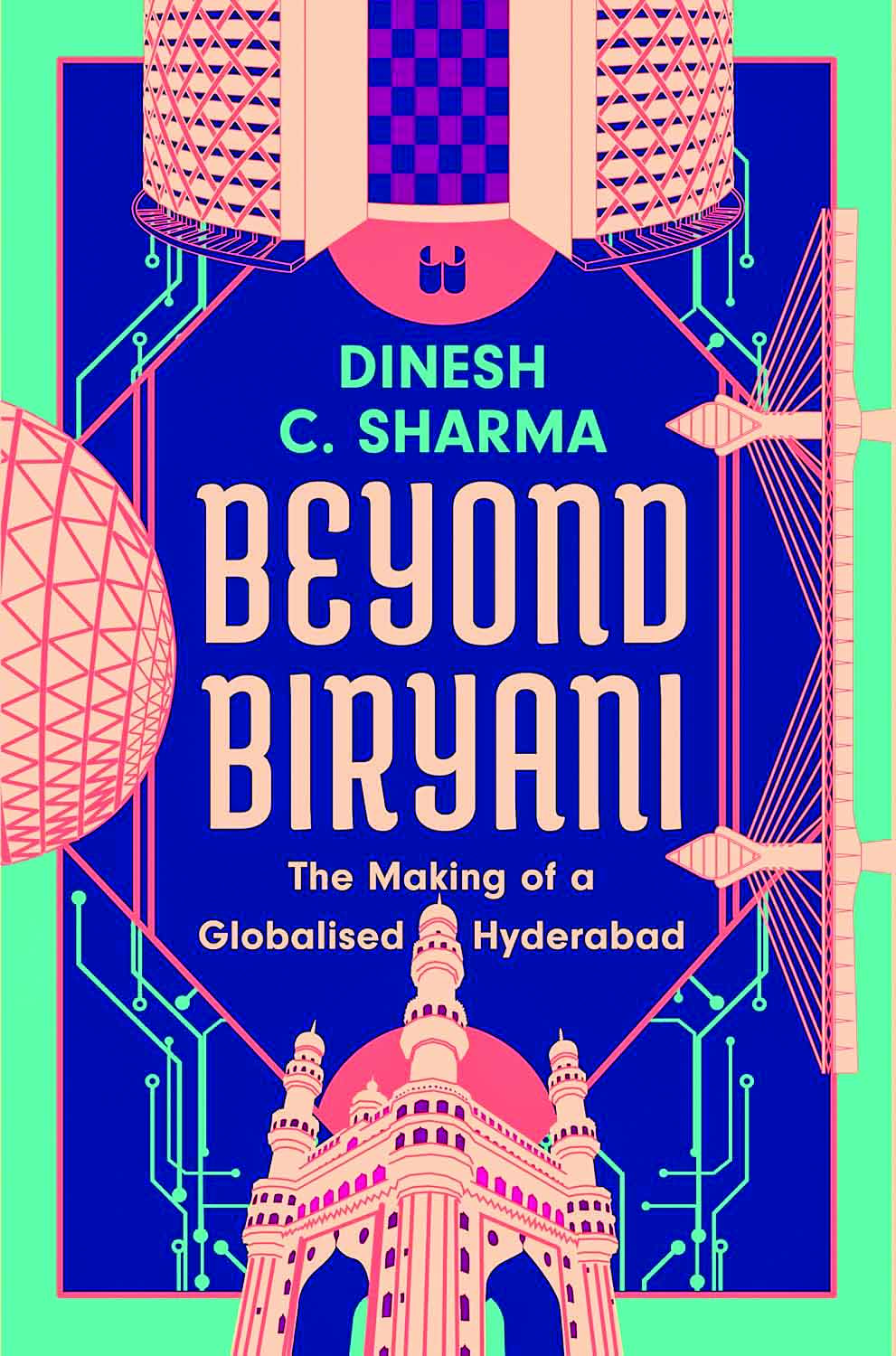

In “Beyond Biryani: The Making of a Globalised Hyderabad (Westland, 2024), journalist-turned author Dinesh C Sharma has showcased how Hyderabad came out of isolation in 1948 [ on account of Nizam rule] to become a part of the larger project of nation-building from information technology to large industries, steel plants, fertiliser factories, heavy machinery plants, power generation plants and a nucleus for developing more scientific institutions.

On August 26, 1995, nine months into NT Ramarao’s third term as chief minister of Andhra, Naidu, his son-in- law and trusted lieutenant, rebelled against him. Naidu defended his coup, saying he had been forced to act against his father-in-law because of NTR’s second wife Lakshmi Parvathi’s growing influence over party affairs and on the state government. Lakshmi Parvathi was NTR’s biographer and he had married her in 1993, much against his family’s wishes.

Dinesh Sharma says once in saddle, Naidu sensed that Hyderabad had almost everything needed for it: a good base of technical manpower — a functional STP, central PSUs engaged in technology-related areas and a string of research institutes and entrepreneurs willing to take the plunge. But it lacked the basic infrastructure like a technology enclave, dependable power supply, good road infrastructure, international airport and a social infrastructure conducive for young professionals. Naidu government worked on each of these elements simultaneously and marketed the city aggressively to investors in India and abroad.

Naidu adopted the science park model, which had been tried successfully in the West as well as in East Asian countries like South Korea, Taiwan and Malaysia as a vehicle for technology-based economic growth and development. The HITEC City and Genome Valley developed quickly as catalysts for boosting economic growth and exports. They could take a shape and yield results due to several domestic and external factors, not solely due to the political will and aggressive marketing as is often projected.

The Y2K problem, the internet and dotcom booms, and platform shifts were among the demand-side factors that made economic sense for American and European corporations to outsource. They found Hyderabad an attractive option due to a good supply of skilled people. In the same way, the process patent regime helped pharma companies in Hyderabad cater to the growing demand for generic medicines in several countries. The Genome Valley attracted foreign companies as the change in the patent regime after 2005 created demand for contract research, R&D outsourcing and third-party clinical research business.

Among the biggest domestic factors that favoured Naidu was the emergence of coalition politics at the centre. The support of Naidu’s TDP was crucial for the survival of successive political formations that ruled in Delhi after the Congress party lost power in 1996. This turned a regional leader like Naidu into a kingmaker on the national stage. It meant he could swing policy decisions of the Central government in favour of Andhra Pradesh at will. Naidu faced no hurdles in getting the Centre’s approvals whenever needed, including for his frequent foreign trips to market Hyderabad. He engaged in what has been called ‘economic para-diplomacy’ that saw him holding bilateral talks during his business trips and getting heads of state flying straight to Hyderabad.3

According to Sharma, barring a short period during 2014-15 when there was uncertainty about the future of Hyderabad as Andhra Pradesh was bifurcated to form Telangana, the twins states of Andhra and Telangana have been lucky in receiving continuous political support for the development of the technology sector in the two states. “A broad consensus about the need to promote information technology since 1991 created a favourable atmosphere for attracting domestic and foreign investments.” Sharma writes adding how the reform policies and focus on IT continued under Y.S. Rajasekhar Reddy of the Congress party, who succeeded Naidu. Similarly, K. Chandrasekhara Rao of TRS, who came to power after the formation of Telangana state in 2014, not only continued the support to this sector but further increased it. He inducted his son K.T. Rama Rao, a former management professional, as the minister for IT. A postgraduate in biotechnology and MBA in marketing, Rama Rao aggressively marketed the new state to investors in IT, biotechnology, as well as other emerging areas. There was no change in the policies for the IT and biotechnology sectors after the assembly elections in December 2023 which saw the Congress party elected to power and Revanth Reddy taking over as chief minister in Hyderabad.

Sharma’s “Beyond Biryani: The Making of a Globalised Hyderabad” offers an absorbing account of Hyderabad and its transformation from being a city of nawabs, the Charminar and biryani to a modern, vibrant metropolis. In an engaging and non-judgmental manner, Sharma also tells us how the Britishers steered the city in the direction of developing a scientific temper and how Nizams of Hyderabad too championed the cause.

We also learn and discover the workings of Chloroform Commissions to Ronald Ross’s discovery of malaria; from the setting up of Osmania University, India’s first vernacular university, to the newest Indian state’s capital pushing for industrial laboratories, scientific research and strategic forays into nuclear fuel and missiles. Hyderabad today is a true globalised city while strengthening deep roots in its cultural heritage and of course, mouth-watering Biryani.