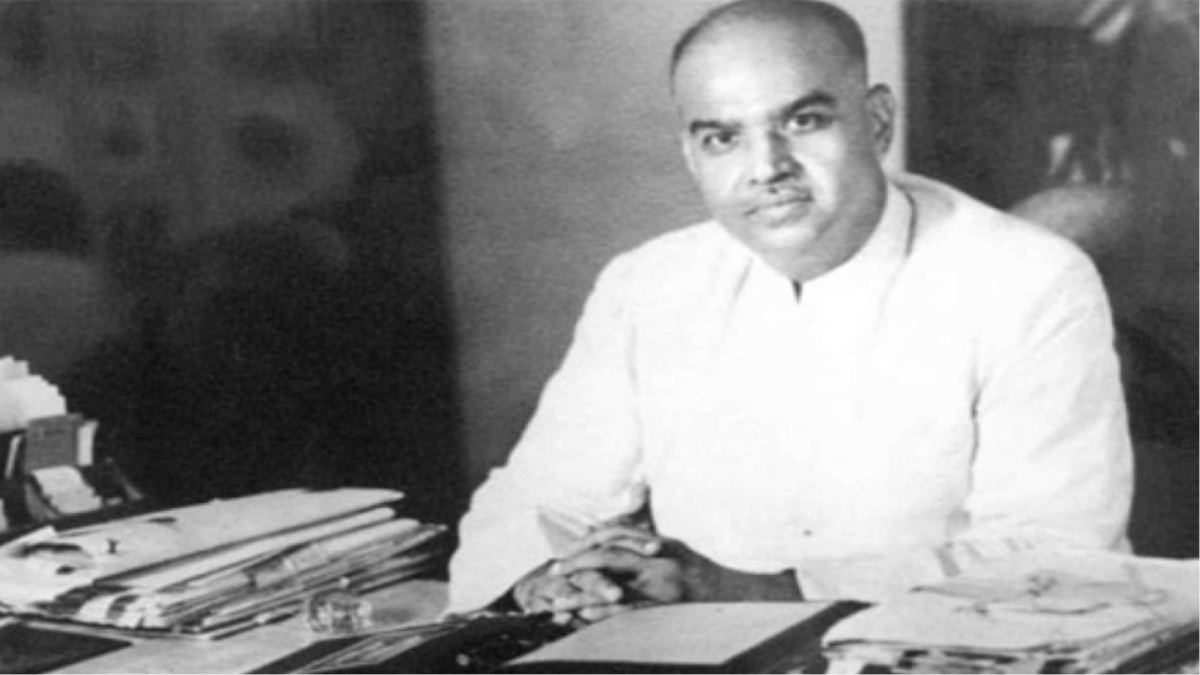

For over seven decades since Independence, Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee’s contribution to India’s national life was largely ignored and marginalised. The Nehruvian consensus that dominated India till the summer of 2014 ensured that Syama Prasad’s legacy and contribution were consigned to the periphery and were either minimised or misinterpreted.

There is something about Syama Prasad’s persona and politics which continues to unsettle some — especially those who have, in the past, opposed India’s freedom, had sabotaged the Quit India movement in favour of the British, had opposed the INA, had supported Jinnah’s demand for Partition, had vocally stood up for the demand of Pakistan, had rejected India’s freedom as a “false freedom” and had launched an armed insurrection against the newly independent Indian state.

The section among the academia and intelligentsia who marginalised and suppressed Dr Mookerjee legacy ensured that generations of Indians and Bengalis grew up without ever hearing of Dr Mookerjee’s contribution to firming up India’s freedom and in cementing her integration and unity. They were deprived of the history of how he thwarted Jinnah’s design of trying to include the whole of Bengal in Pakistan, they were not narrated his epic effort in breaking the design of Pakistan and in launching a massive public movement supported by Hindus of Bengal and by the majority of Bengal’s leading thought-leaders for demanding that a portion of Bengal be carved out and retained in Indian Union. To use his words, “We must have our own territory where we can live as free men, and build up our own culture, our own social and economic life in accordance with our best tradition.” Seventy-five years after that epochal move Dr Mookerjee’s words continue to be strikingly fascinating.

In his public statement in March 1947, on should Bengal be divided into two provinces, Dr Mookerjee argued, thus, “We have demanded that both Hindu Bengal and Eastern Bengal must remain within one India. We are against Pakistan in any form or shape. It does not however depend on the Bengali Hindus alone whether the division of India will be prevented or not. If Hindus and other nationalist forces throughout India are really determined not to allow any portion of India to go out of the Indian Union, they will get the largest measure of support from Bengali Hindus. If on the other hand an attempt is made to place Bengal out of the Indian Union, due to commitments with which the British Government, the Moslem League, and the Congress are closely associated, we shall at any rate break the solidarity of Eastern Pakistan, save one area of Bengal and link it up with the Indian Union.” This he did with utmost dexterity and determination.

A section among the ideology-driven gate-keepers of Indian historiography have tried to portray the demand for the creation of West Bengal as a motivated move by “caste-Hindus” all belonging to the “upper class” “Bhadralok” intelligentsia both political and commercial to safeguard their monopolies. But the truth is far removed from such a motivated assessment. In fact, prominent scheduled caste leaders of that era including Babu Jagjivan Ram, Pramatha Rajan Thakur, Radhanath Das, secretary of the Depressed Class League to name a few, actively supported Dr Mookerjee’s call for the division of Bengal. That Jinnah was handed over a ‘moth-eaten Pakistan’ was largely because of Dr Mookerjee’s political dexterity and mobilisation.

That there exists today a portion of Bengal in India is because of Dr Mookerjee’s exertion and political sagacity and yet how deftly was this portion of our history erased and how soon was this chapter forgotten or blanketed by the Nehruvian establishment. For seven decades it was only Bharatiya Jana Sangh, the party founded by Dr Mookerjee, and its political successor Bharatiya Janata Party which kept the shades of this history floating in face of a strong and organised intellectual opposition which monopolised and controlled all avenues of expression and dissemination.

The story of the Bengal Famine, especially of how Dr Mookerjee addressed this gargantuan challenge, how he disseminated its truth throughout the country and how he exposed the complicity of the British administration, and the Muslim League government of Bengal in dragging the province through one of the most calamitous manmade disasters of genocidal proportions of the twentieth century needs to be reiterated and widely narrated.

The Bengal famine, which exterminated over three million people, has been examined in the past, but Dr Mookerjee’s role in it has been minimised or distorted. His side of the story, as one involved in the Herculean task of providing succour to the victims, has been repeatedly brushed aside in the past. Who would know, for instance, that it was he who had organised the largest non-official relief effort for the victims of the famine? Who would know that his appeals elicited a huge response from across the country with business leaders and political leaders, religious and social institutions responding to his call for support in providing relief? Who would know that under Dr Mookerjee’s leadership a multi-course relief was provided, for days on end, to more than a lakh famine victims? Across 24 districts, the Hindu Mahasabha under Dr Mookerjee maintained 227 relief centres. Besides this, the Mahasabha also supported 31 other organisations in their relief work. Relief work under Dr Mookerjee’s leadership was not denominational, though the relief centres run by the Muslim League and its band of Razakars, coerced victims into a convert-for-relief programme.

Throughout that trying period Dr Mookerjee spoke and wrote on the Bengal famine besides organising relief and appealing to social and political leaders across India to come to the succour of the people of Bengal. Besides exposing, in the Legislative Assembly, the perfidy of the Muslim League government which colluded with the colonial establishment to divert food-grains and also ensured that some benefitted through this pilferage, Dr Mookerjee also ensured that whole of India got to know of this calamitous event that was unfolding in Bengal. His writings on the Bengal Famine in Bengali published as ‘Panchasher Manwantar’ — the famine of 1350, which is the year 1943, have left for posterity a first-hand account and analysis of the famine. Yet it was deliberately omitted from the discourse on famines, politics, and the various historical and political assessments of modern India both pre and post-independence.

For a generational reassessment of Dr Mookerjee’s role, contribution and legacy works such as The Bengal Famine: An Unpunished Genocide which is a commentary on and translation of Dr Mookerjee’s work must have wider dissemination and must generate robust debate and contribute to a narrative course correction. The seventy-fifth anniversary of India’s independence offers us that opportunity. This period must mark the beginning of a collective effort to republish, re-assess, re-state and disseminate more such works that have faced motivated neglect and marginalisation both political and ideological.

Translator and commentator Sudip Ka Purakayatha’s effort comes across as a very timely and much-needed intervention. It shall contribute hugely to the effort being made to re-situate Dr Mookerjee in the national narrative and consciousness and coming as it does against the backdrop of the seventy-fifth year of India’s Swaraj it is a fitting tribute to one of the greatest patriots and statesmen of modern India.

The writer is the director of Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation, New Delhi. The views expressed are the writer’s personal.

The story of the Bengal Famine, especially of how Dr Mookerjee addressed this gargantuan challenge, how he disseminated its truth throughout the country and how he exposed the complicity of the British administration, and the Muslim League government of Bengal in dragging the province through one of the most calamitous manmade disasters of genocidal proportions of the twentieth century needs to be reiterated and widely narrated.