The politics regarding the three Ordinances have taken over Parliament’s Monsoon Session. As it is the session was a truncated one, to be held during the pandemic. And it was not without risk with 25 MPs and 56 of the staff testing positive. There were elaborate arrangements made, especially keeping social distancing in mind. MPs marked attendance via an app, RT-PCR tests were conducted within the complex and so on. But was the risk worth it?

For, in the end, it was back to the old-fashioned way of doing politics, as opposition MPs rushed to the well claiming that the government had tried to bulldoze a voice vote through on the three controversial Ordinances that were brought about by the government soon after the marathon lockdown ended. This was a sad end to a fiery debate on the subject that saw some well-crafted arguments on both sides, not to mention high drama that flagged it all off with the resignation of a Cabinet minister at the start of the session. Why did Harsimrat Kaur Badal wait till the Ordinance reached Parliament before resigning, and did not do so at the time the Ordinances were passed, on 5 June 2020? Why did the Opposition wait as long before taking up the issue? Well the answer lies in the simple fact that it was only after the farmers hit the streets that the political parties realised the ramifications of this move and decided to join the cause with a very influential vote-bank.

But first, a look at what these pro-farmer legislations are all about: The most controversial was Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) ordinance (now a Bill), which allows farmers to sell produce outside the markets notified under the various state agricultural produce market laws (state APMC Acts). The second one, the Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services legislation overrides all state APMC laws with reference to the sale and purchase of farm products, bringing uniformity into contractual farming rules (and state APMC Acts) across India. While the third seeks to bring changes into the list of essential items whose prices are regulated by the government.

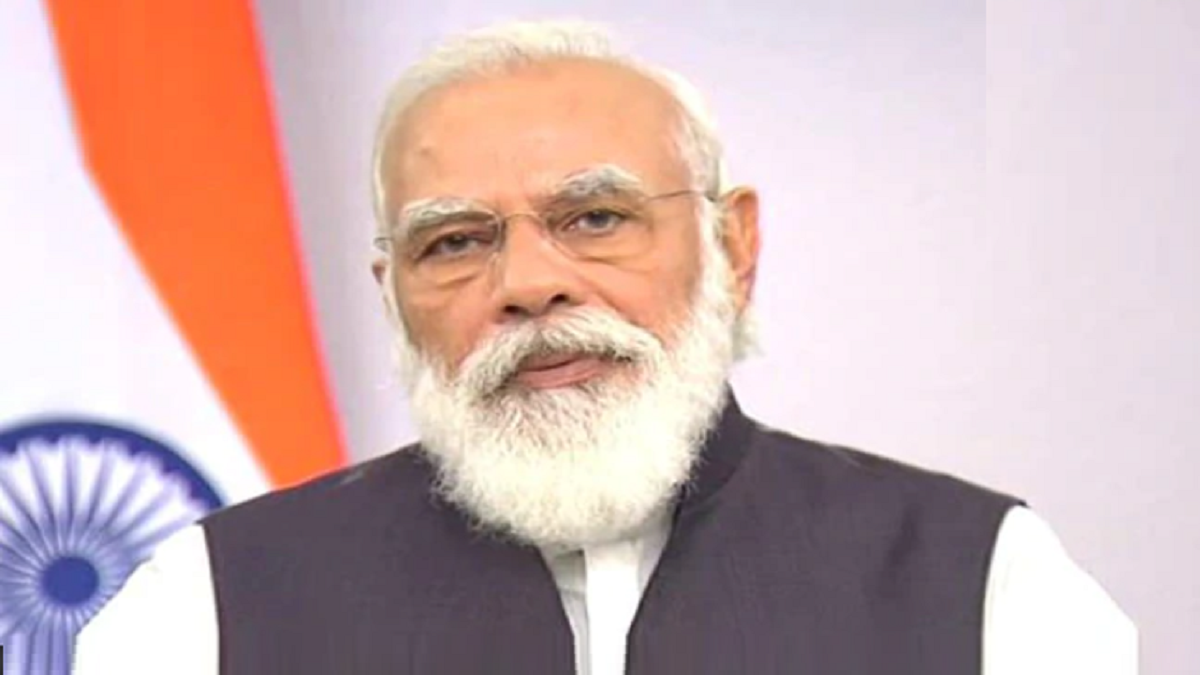

While the government claims that these are for the betterment of the farmers, it is clear that the targeted beneficiaries disagree. They see these changes as a move to please big firms, to do away with the MSP and pronounce a death knell on the farmers’ with small holdings (that comprises about 86 percent of the farming population). Seeing the farmers hit the streets the government clarified — with the PM himself issuing a statement — that this was a move aimed to reform the lives of farmers and that MSP would not be done away with but it was too late because the distrust had already set in. The Akali Dal, which is the BJP’s oldest ally, played it smart, realising that this was a move that was going to boomerang on its vote-bank. Don’t forget that the SAD is largely a rural-based party while it was the BJP that dominated the urban Punjabi voter. It has been a combination that worked, even during demonetisation. And so naturally the SAD is not keen to severe ties. Which is probably why during his intervention in Parliament SAD MP Naresh Gujral also reminded us about how much the Modi government had done for the farmers. But there was no way even an articulate orator like him could defend the Modi government’s latest move and so he ended his speech recalling what the Gurus have taught us about “qurbaani” and “zulm ka saamna karna” (sacrifice and taking on injustice). He pointed out that today the farmers feel that a “zulm” is being instigated against them and so the Akali Dal was standing by them.

Other parties too such as the TMC, the AAP and the Congress have taken up cudgels against this move, while the AIADMK and the YSRCP have supported the government. However, it was the demand that the bills be sent to a standing committee (read delay) that had the government overruling this with a voice vote, and therein began the ruckus that saw the expulsion of eight MPs from the Rajya Sabha.

Why didn’t the government agree to the standing committee, especially after seeing the farmers protest all over the neighbouring Haryana, Punjab and other states? There are many reasons but the obvious one is that there are no rollbacks in Modi’s playbook. Whether it was demonetization or the unwieldy GST, it is clear that once he has made up his mind (right or wrong) he doesn’t need popular approval. He has the numbers to push the decision through and this is what he does. And to give him credit, he also manages it to sell the same decision to the public when it comes to the crunch — voting time. For, don’t forget after demonetisation and GST everyone thought he had lost the BJPs critical vote-bank, the rural poor, traders, small shopkeepers and banias. But in the end, he ensured that first the party won the critical state of UP in 2017 and then the rest of the country in 2019.

So before we write off the farmers’ vote away from the BJP, let’s wait and watch the one man who knows how to take a controversy and repackage it as an election winning move. Watch this space.