The three new agriculture laws implemented by India in September 2020 with little public or legislative debate have piqued the world’s curiosity. The initiatives were portrayed as a gift to farmers by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government, but farmers in various Indian states, headed by smallholders in Punjab and Haryana, have refused to accept them.The three laws are:

• The Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act,

• The Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act and

• The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act.

The court stated that dozens of rounds of negotiation between the Centre and farmers had yielded no breakthroughs, despite the fact that senior individuals, women, and children among the protestors were exposed to major health risks caused by the cold and COVID-19. It was stated that deaths had already happened, not as a result of violence, but as a result of illness or suicide. The court praised the protesters’ nonviolent character and indicated that it did not intend to stop them.Essentially, in the midst of a pandemic, with a critical vaccination drive underway, the government appears to be employing a two-pronged strategy to break the impasse: reaching out to farmers to bridge the trust deficit in farm laws, and combating disruptive forces that are attempting to take advantage of the situation.

Farmers are concerned that agriculture sector changes would result in the abolition of the minimum support price (MSP) system and the abolition of APMC markets. The government buys farm commodities at a fixed price under the MSP framework. The MSP guarantees that farmers are guaranteed a set price, regardless of supply and demand limits. Farmers have been calling for legislation to ensure that agricultural food is purchased at the MSP. They also urge the government to repeal the Electricity Act modifications.Farmers are concerned that it would lead to the corporatization of agriculture, which will eventually force them out of the industry. They contend that the sale of agricultural produce would be governed by contracts, rendering the MSP regime ineffectual. The law permitted farmers to engage into a direct arrangement with the buyer before to the sowing season and sell their goods at the agreed-upon price at the time of contract signing.

What were the main issues in THE FARMER’S PRODUCE TRADE AND COMMERCE (PROMOTION AND FACILITATION) ACT, 2020 OR THE FPTC ACT as regarded by the farmers?

Though farmers objected to all three agricultural laws, the main issue was this Act, commonly known as the ‘APMC Bypass Bill.’ Cultivators were concerned that its provisions would undermine the APMC mandis.

Sections 3 and 4 of the Act permitted farmers to sell their goods in regions beyond the APMC mandis to purchasers from inside or outside the state. Section 6 barred the collection of any market charge or cess under any state APMC Act or other state law in connection with trading outside the APMC market. Section 14 overruled the contradictory sections of the state APMC laws, while Section 17 enabled the Centre to make regulations for enforcing the law’s provisions.

Farmers were concerned that the new laws would result in insufficient demand for their goods in local marketplaces. They said that moving the produce outside of mandis would be impossible due to a lack of resources. This is why they sell their goods at prices lower than MSP in local marketplaces.

Farmers were also upset with the provisions in Section 8 of the law that stated that a farmer or merchant might approach the Sub-Divisional Magistrate (SDM) to reach an agreement through conciliation procedures. While farmers claim they lack the right to enter SDM offices for conflict resolution, others say this amounts to seizure of judicial authorities.

POSSIBLE ISSUES WITH FARMERS (EMPOWERMENT AND PROTECTION) AGREEMENT OF PRICE ASSURANCE AND FARM SERVICES ACT, 2020

Sections 3-12 of the statute attempted to provide a legal framework for contract farming. Before the planting season, farmers might get into a direct arrangement with a buyer to sell their products at predetermined pricing. It enabled farmers and sponsors to enter into agricultural partnerships. The law, however, made no mention of the MSP that purchasers must provide to farmers.

Though the Centre claimed that the law was intended to liberate farmers by allowing them to sell anywhere, farmers were concerned that it would lead to the corporatisation of agriculture. They were also concerned that the MSP will be eliminated. Critics also claimed that the contract system would expose small and marginal farmers to exploitation by large corporations unless selling prices were continued to be regulated as they were before to the new law’s implementation.

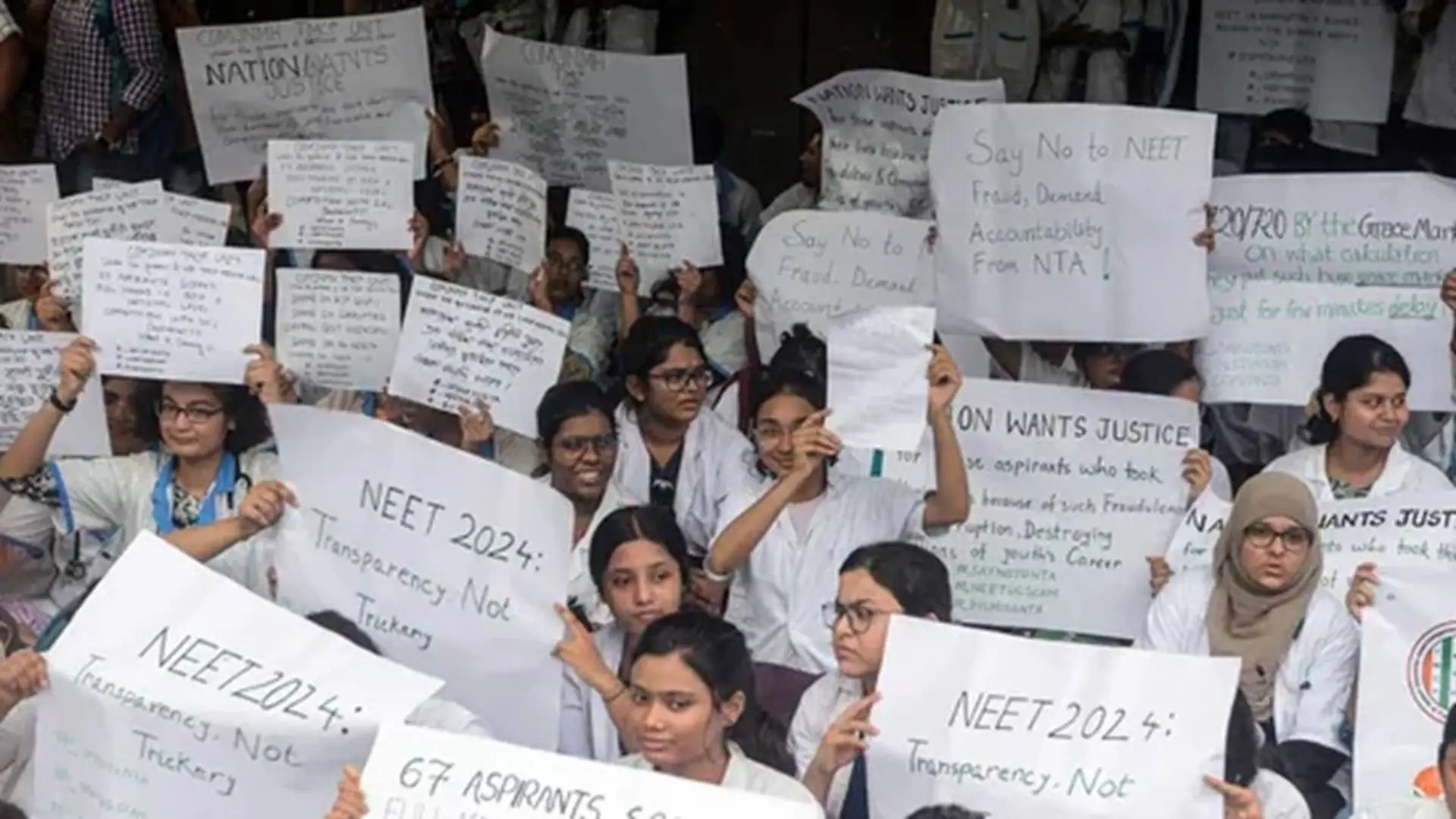

HOW DID THE FARMERS REACT TO THE FARM BILL?

Despite the potential benefits, both parties were unable to reach an agreement on the farm laws, which resulted in their repeal. Farmers who have been protesting at Delhi’s borders and in their states since last year have rejected the Central government’s offers to alter the contentious new agriculture rules. They said that the plan was insufficient and accused the administration of being “insincere,” while also warning the Parliament to step up their protests. Parliament approved these Acts during the monsoon session in 2020. Farmers have long feared that the Centre’s farm reforms will pave the way for the demise of the MSP system, leaving them at the whim of large corporations. However, no resolution was reached, and no date for the next round of discussions was set for the first time. Following the failure of these discussions, the Supreme Court suspended the execution of these farm legislation. Farmers were overjoyed when these rules were removed on November 19, 2021.