A genie that had been throttled in a bottle since 1947 appears to have been released. A worrisome incident that left many from metropolitan areas appalled is a recent encounter which shows an emerging power semantics of public space. On the morning of 6 April 2021, in Gurugram’s Nathupur village market, three young boys in their early thirties, clad as sadhus, went from shop to shop, asking for money with thunderous slogans of “Jai Shri Ram”. A shopkeeper greeted them delightfully with “Jai Siya Ram”, but surprisingly, the sadhus appeared highly displeased and shouted back angrily, “Say ‘Jai Shri Ram’, ‘Jai Siya Ram’ is wrong.” There was a bit of a tussle and the sadhus, who were perceived as a nuisance, were made to flee by a united front of shopkeepers. This community village market is a cultural space for embedded normative exchanges which highlight the most pristine national inclinations. But the slogan of “Jai Shri Ram” has become an enigma for most Indians as its content and spirit do not match. Who has created this segmentation, and why?

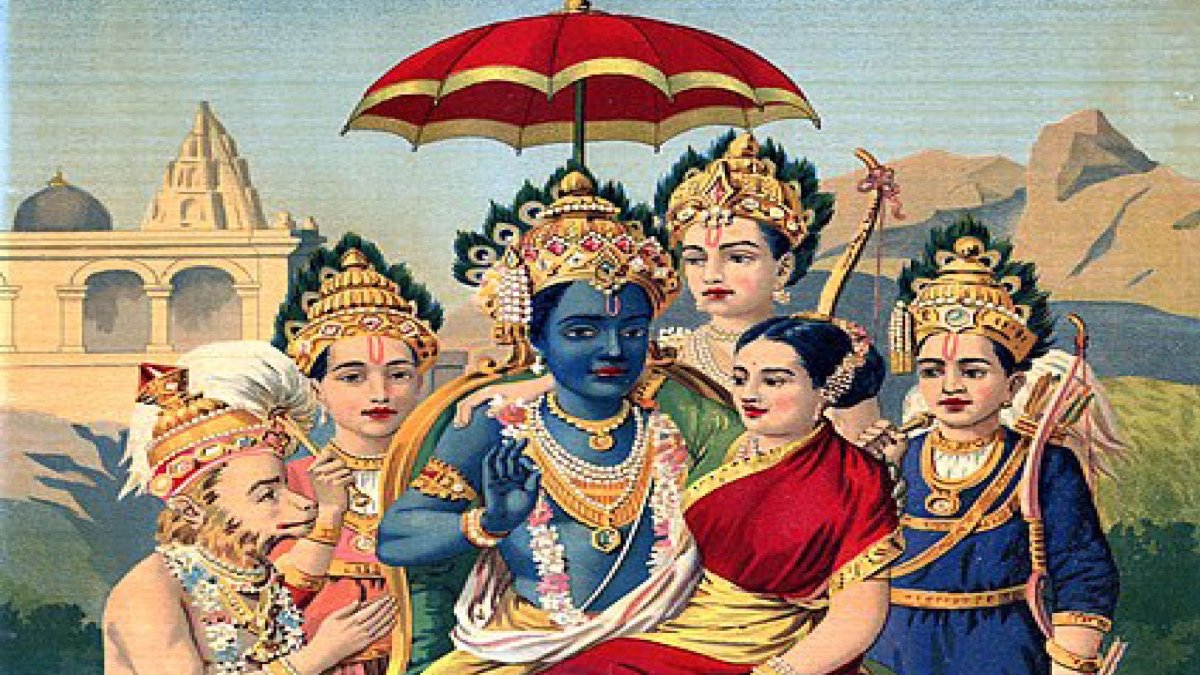

Columnists often face the impossible task of balancing the forbidden (not everything can be written) with the forsaken (not everything can be ignored). Their universe of elliptical proximity to their subjects is jammed with justice-seekers in the waiting, for attention, consideration and even resurrection. Ironically, it appears that the current dispensation of Indian politics has turned Shri Ram, an incarnation of God, worshipped as a revered divine deity, into a consecrated yet perforated sachet of public delivery. The everyday greeting of “Jai Siya Ram” from benign communities inhabiting the holy land of Ayodhya to Chitrakoot resonates to the shores of Rameshwaram in search of the deity’s tales of tolerance, forbearance and humility flowing throughout the 5th century BCE epic, the Ramayana.

At the Ayodhya bhoomi pujan ceremony, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had used the slogan “Jai Siya Ram” instead of “Jai Shri Ram”, acknowledging the fact that Mata Janaki or Sita, who represented “bhoomi” or Mother Earth has a central role in the Ramayana. His speech was a generous acknowledgement of the role that Mata Janaki or “Siya” played in the life of Rama. By referring to her moral strength as a ground for bhakti or devotion and faith, he in fact highlighted the bond that the Ramayana weaved together in its characters, from Bharat to Ahilya, Kewat, Shabri, Sugreev, Vibhishana, and finally in conceding before the knowledge of Ravana, despite slaying him in war. Love spares no one and that is the essence of the Ramayana, embedded in the warmth of the community greeting of “Jai Siya Ram”. Those who heard this speech felt an invocation of love and harmony in social relationships which have been strained since 1984. Nonetheless, one would agree that no content or any meaningful usage can be without a norm, especially when it is about its intentional usage, while laying claim to a slogan such as “Jai Shri Ram” or “Jai Siya Ram”. PM Modi was right in acknowledging the role of Mata Janaki in “Jai Siya Ram”, but why does this mother incarnate disappear among his followers when they roar, nay, let out the war cry of “Jai Shri Ram”? What made Mamata Banerjee object to the outcry of “Jai Shri Ram”?

The slogan “Jai Shri Ram” has an anecdotal past which reveals that it has been used to provoke incendiary thoughts and actions to achieve an objective which is otherwise not lawful, which is socially disliked and may not be approved by the administration. The slogan, with a militarised invincibility to its tone, a threatening call akin to “Allah hu Akbar”, screeches through social divisions, creating schisms and provocations to accomplish conspiracies of brutal punishments against sinners, the unchaste and the promiscuous. This slogan has been used to glorify social evils and customs in the name of sanitising society such as the glorification of the dreadful act of “suttee” or “sati”. An interesting case from 1871 may bring greater clarity in understanding the normative links of this slogan. In Queen v. Mohit Pandey & Others (1871), the woman had been prepared to commit suicide by “suttee”, as was expected by her husband’s family. As she moved towards the pyre, her stepsons followed her, shouting slogans of “Jai Shri Ram” to create an environment of bizarre but powerful religious nostalgia for a cause larger than a woman’s life, lest she change her mind on nearing the pyre. When conspirators of a grotesque self-infliction become vanguards of a holy army, slogans can stifle minds, appropriate to the accomplishment of an offence. Evidence that emerged from the heinous act of burning the woman with her husband’s body revealed active connivance and unequivocal support of the suicide by the accused and justified the inference that the provocative sloganeering was indeed a conspiracy for commission of the “suttee”. The District Sessions Judge of Ghazeepore, S.N. Martin, sentenced the accused under Section 306, IPC to five years of rigorous imprisonment for abetment to suicide.

On the whole, the Ramayana’s true spirit and character have been badly dented by the enterprise of politics which becomes dependent upon slogans which are used to push male supremacy, militarised followers and provocative communication. In fact, during the last years of his stay at Kashi (now Varanasi) Acharya Tulsidas mentioned how malice, hatred and sectarianism were spread by similar unscrupulous pundits and miscreants who mocked his common man’s imagery of Rama. In Ramcharitamanasa, he has referred to such miscreants as: “Hasi hahi krura kutila kavi cari/ Je par dusana bhusana dhari.”

Those mundane pundits would later touch Tulsidasa’s feet and beg for atonement at the Kashi Vishwanath temple but what about these muscle-flexing sadhus desecrating the name of Rama by filling it with aggression, violence, hate and a deadly ambition to capture political power through the weapon of “Jai Shri Ram”? Will the final courtroom of Rama ever provide them an opportunity for penitence or as the renowned Urdu poet “Zauk” expressed: “Charakh par baith raha jaan bacha kar Isa;/Ho saka jab na mudaba mere bimar ka.” (Hazrat Isa was sent as a messenger of God to earth to reform people deviating from the path of righteousness but He soon got frustrated and took refuge in heaven again.)

The author is a former Professor of Administrative Reforms & Emergency Governance at JNU, Delhi. The views expressed are personal.