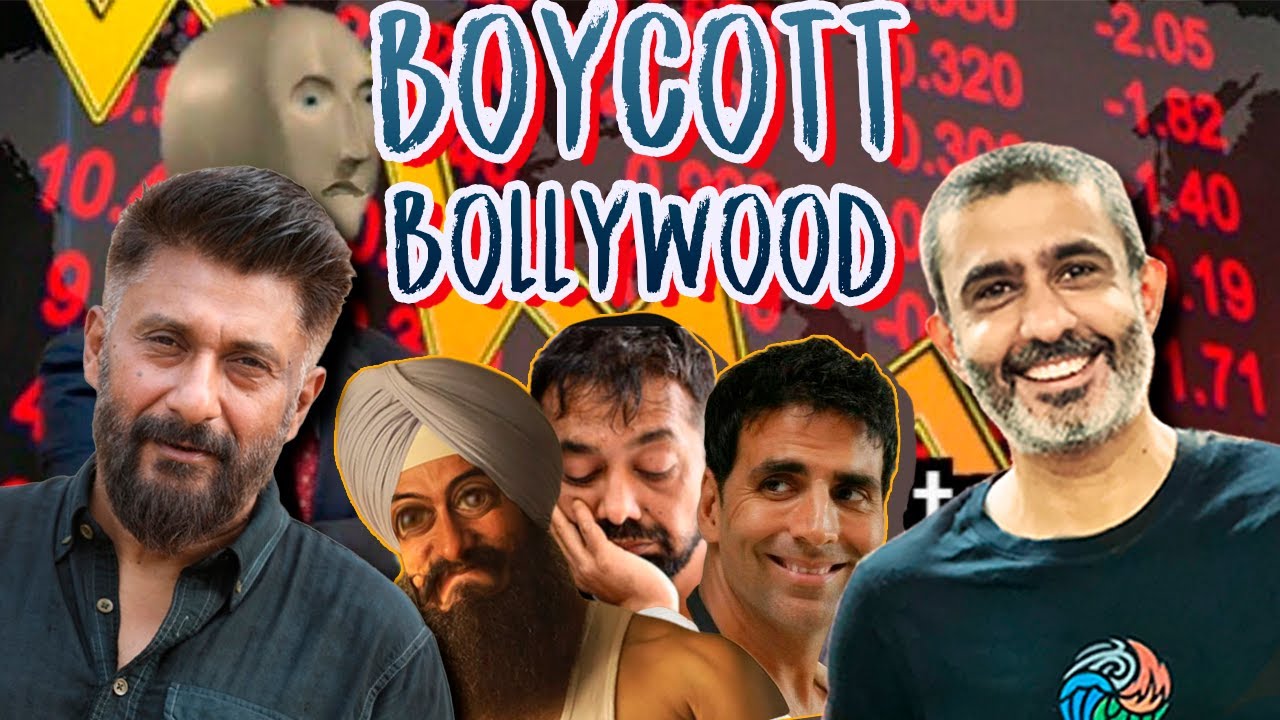

The idea of “boycott” was born in Ireland. Charles Cunningham Boycott was a British land tax collector whose ways were so despotic that peasants and farmers rose against him in the 1880s and, in “woke” parlance, they cancelled him, giving birth to the word “boycott”. Boycotts have since been used worldwide as an effective method of protest and as a tool for better collective bargaining. Cut to contemporary India, and the spectre of boycott is haunting cinema in a very different way, changing it from a tool of protest to a toxic tool of bullying and intolerance. “Boycott armies” are on a rampage on trigger-happy social media. This year, as the film industry slowly limps back to normal after being bruised by Covid-19 and the lockdowns, dozens of films have met with calls for a boycott. The latest of these trending hashtags was #BoycottBrahmastra, targeting Brahmastra: Part One– Shiva, an adventure-fantasy film written and directed by Ayan Mukerji and starring Bollywood heartthrob Ranbir Kapoor. It is not like it began this year, it dates back to 2014 when Aamir Khan’s film “PK” faced a lot of flak and some people called for its boycott across the country for the film’s poster, and the depiction of Hindu gods in the film. In the film’s poster, Aamir was shown naked with a radio covering his private parts which triggered the moral police and an FIR was registered against the actor. The film was also criticised for showing Indian yogis in a negative light which was not well received by some Hindu extremist organizations. Later in 2016, Lipstick Under My Burkha faced boycott from the All India Muslim Tehwar Committee had objected to the portrayal of Muslim women citing reasons of hurting religious sentiments and had called for legal action against the film. Again, in 2018, Deepika Padukone starrer Padmaavat was embroiled in several controversies both before and after its release. In fact, the film began facing problems since it went on the floors and its set was attacked by religious extremist groups. It received flak for an alleged intimate scene between the Muslim ruler Alauddin Khilji and Hindu queen Padmavati, the songs Ghoomar was criticised because Padukone’s belly was visible. Later, the filmmaker had to add VFX effects to cover it. The film’s title was also changed from Padmavati to Padmaavat. The prime reason for the boycott was said to be the futility of remaking a movie that is already popular and well-loved among Indian film buffs. A Bollywood treatment, it was argued, would ruin the story by turning it into a Karan Johar-style melodrama. There was also old anger against Aamir Khan. Once a nearly universally beloved actor, Aamir earned the ire of those on the right side of the political spectrum first due to his movie “PK”. Directed by Rajkumar Hirani, the film satirised superstitions and dogmatic religion by showing the perspective of a literal alien (played by Khan). Many accused Hirani and Khan of unfairly targeting certain practices among Hindus while not doing the same to Islam. The reputation of Khan was exacerbated when at an event he spoke about how his wife (now divorced) Kiran Rao was fearing for their children amid the alleged rising intolerance in the country and was thinking of moving abroad. The comments were said against the backdrop of the assassination of intellectuals and the killing of Muslims. The comments created a lot of political furore as political parties played their usual blame game. There were questions of the nepotism debate, one side of which says that the industry is closed to outsiders, who, despite their talent, have to struggle to score even supporting roles. Star kids, on the other hand, get plum roles straight out of the cradle. Or something. The claims that nepotism is prevalent—have been appropriated by actors like Kangana Ranaut, who say they are in this position because of their toil, not because of “recommendations”. Things got worse after Sushant Singh Rajput died by suicide. A talented young actor, his death was blamed on the alleged debauchery of Bollywood—that he was introduced to drugs by his exgirlfriend Rhea Chakraborty. Sushant, it was said, was dissatisfied due to his position in the film industry despite his visible talent. What followed was months of forwarded private WhatsApp messages in which Rhea allegedly apprised Sushant of the delights of being high on marijuana and so on. There were also other factors at play because of which viewers are spending less on Bollywood/Hindi films. Interestingly, South films, including their Hindi-dubbed versions, have done exceptionally well in the last few years, while Bollywood movies have struggled to find viewers. In fact, celebration has gripped India as the “Naatu Naatu” song from S.S. Rajamouli’s “RRR”, a Telugu film, emerged victorious at Golden Globes 2023. Superstar Shah Rukh Khan was among the Bollywood biggies hailing the historic win. Earlier on Wednesday, Rajamouli cheered for SRK’s “Pathaan” trailer. He tweeted, “The trailer looks fab. The King returns!!! Lots of (heart emoji) @iamsrk. All the best to the entire team of Pathaan.” Hours later, SRK replied to Rajamouli’s tweet and congratulated him over ‘RRR’ win at Golden Globes. SRK wrote, “Sir just woke up and started dancing to Naatu Naatu celebrating your win at Golden Globes. Here’s to many more awards & making India so proud!!” Several celebrities greeted the team for winning the Best Original Song award for the song “Naatu Naatu”. The popular perception behind Bollywood’s poor show is that the industry is losing its connection with the current generation of movie watchers and producing bad films, one after another. While this may be one of the reasons why viewers are spending less on Hindi cinema, there are several other causes, including financial ones as well. Because of the decline in single screens, most films are now getting released in multiplexes where ticket prices are three to four times more than single screen theatres. South movies have an edge over Bollywood as 62% of the total single-screen theatres in the country are in South India. North India has a share of only 16% followed by West with 10% of all single screen cinema halls. Changing demographic profiles and behavioural changes across the states are also affecting Hindi films. The report says that millennials these days use online platforms to watch movies of their favourite genres. They prefer to wait for new movies to watch from the comfort of their homes at any time. With most of the millennial population in the North, changing movie-watching habits of people is affecting Hindi films. In contrast, a higher share of the elderly population in South Indian states appears to be benefitting South movies as well. South Indian states have higher share of elderly people who would still prefer watching movies in theatres than on OTT platforms. It is not that the Indian movie fan has suddenly acquired a highbrow, rarefied taste. It’s just that he or she is more demanding now—due to the sheer prevalence of options. The star culture has not disappeared as yet, but it has certainly diminished. Good, well-marketed movies will still find appreciation. They just have to jostle for space against a host of other, and usually better, options now.

Dr S. Krishnan is an Associate Professor in Seedling School of Law and Governance, Jaipur National University, Jaipur.