Intellectual honesty is a crime in any totalitarian country: George Orwell

A few years ago, Shashi Tharoor was on a show with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation to discuss his new book. In ‘An Era of Darkness: The British Empire in India,’ a title possibly inspired by V S Naipaul’s ‘An Area of Darkness,’ Mr Tharoor had written, inter-alia, about the loot and plunder carried out in India by the British over the course of two centuries. A nation that once commanded a lion’s share of the global economy, had, in the writer’s words ‘been reduced to being a poster-child for third-world poverty and destitution.’

During the course of the interesting discussion that ensued, an Englishwoman on the panel with Tharoor wondered aloud why she had not been taught any of this in school. It appears that colonial history has never been part of the school curriculum in the United Kingdom. In England they learn about their kings and queens, European history and the world wars, but not about empire and its excesses. Why is this the case? Is this accidental or deliberate? Is it similar to the ostrich burying its head in the sand? The ostrich does not wish to see approaching danger; the British do not wish for their young, school going population to be confronted with the misdeeds of their ancestors.

A more appropriate comparison may be made with the untrained policeman in the developing world who frequently resorts to the torture of suspects as an aid to investigation. In India too, we can easily find such a policeman who is a caring husband and a good father to his children at home, but doesn’t hesitate to use third-degree torture on suspects he may have arrested on an assorted variety of cases, including petty crime.

Now the policeman’s children know their father to be a kind and caring person. Were anyone to tell the children that their father routinely tortured and beat up prisoners in his custody, often within an inch of their lives, they would, in all likelihood be outraged, even furious at what they would perceive to be a false accusation. They would refuse to believe that their parent who had never even raised a hand on them could ever commit such acts of horrific violence on anyone.

Something similar has happened with the narrative spun at home by colonial powers be it the French, the Dutch or the British. The ruling elite within these nations never thought fit to educate domestic audiences what they were really up to in the territories they invaded: the unfair trade practices, the cruelty, the humiliation, the beatings, the torture, and even the killings of the native population. Had they revealed the terrible truth about what they were really up to in their colonising ventures, it would have shocked the conscience of ordinary, decent people. There may have been, quite possibly, an uproar. In order to prevent any domestic hurdles to their immensely profitable overseas undertakings, the ruling elite thought it best to keep their people in the dark.

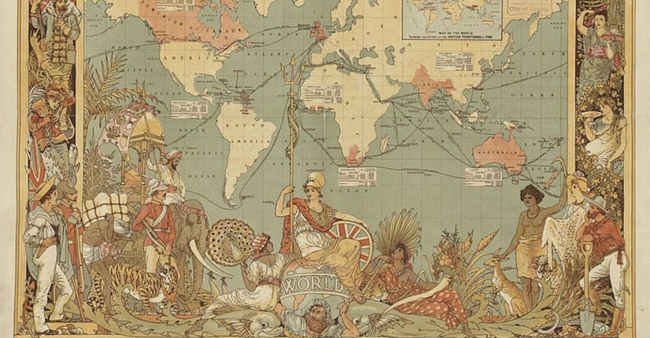

Of course, even if colonial history was not being taught in schools, questions would still be raised: what were the colonisers doing? An alternative, plausible narrative had to be fed to them, not dissimilar to what the policeman would tell his children. The Indian policeman may have been beating up his prisoners, hanging them upside down and even putting chillies and objects into their private parts but all these terrible crimes could never be revealed. An alternative narrative would be fed to them that their father was creating law and order and Papa was out to catch ‘bad people’. Just like the children of the mythical policeman, the domestic populations in the colonising nations were made to believe that their country was on a civilising mission. The natives were a beastly, uneducated lot and they needed the white man to keep them from killing each other. Terrible, dark secrets concerning the overseas missions of loot, pillage, plunder, torture and murder were kept hidden from domestic audiences or downplayed in the extreme.

Nor is this charade over by any means. Historians such as Niall Ferguson continue to write about the great benefits of colonialism. Having never studied colonial history in school many adult Western readers easily buy into such narratives. Many cannot bear to believe that their ancestors were anyone but good people. Forget about Westerners, often enough even British citizens of Indian origin buy into the same narrative. What are the emotional compulsions, if any of such people? It’s probably similar to that of the Westerners. They have adopted a new country for the better life but tell themselves that it’s not only about money. Many genuinely believe that their new adopted country represents higher civilizational values. They might not be entirely wrong here but what they often fail to understand is that there has always been one standard at home and an entirely different one when it comes to overseas interests. In this regard they are similar to the adoring children of the Indian policeman who only see their parent’s benign, kind face, not the brutality that often hides within.

For some time now, efforts have been made to reform the policeman who uses torture as an aid to investigation. Prosecutions have been launched, cameras have been installed inside police stations and training on the rights of accused persons is imparted. In the same way the glaring omission in the history being taught in schools in England is sought to be remedied. Such initiative is coming from those people whose families suffered under British rule. A group of researchers, educators and consultants have come together to form the Partition Education Group. This group has been campaigning for the introduction of a detailed study of Empire in the school curriculum. This is important not only for the British South Asian community, it is pointed out, but also to combat racism in schools.

As George Orwell wrote famously: ‘Intellectual honesty is a crime in any totalitarian country; but even in England it is not exactly profitable to speak and write the truth.’

Rajesh Talwar, the author of thirty-nine books spanning multiple genres, has served the United Nations for over two decades across three continents. His most recent book is titled ‘The Boy Who Fought an Empire.’