Scholar Radha Kapuria at Durham University recently rebutted a lament by another academic and singer, Dr. Madan Gopal Singh, that Punjabis do not celebrate their rivers in stories, song and folklore the way some other Indians, like the Bengalis, do. In her essay titled, ‘Singing the River in Punjab: Poetry, Performance and Folklore’, she writes that far from being forgotten, the rivers remain ubiquitous, even omnipresent in popular Punjabi imagination, thanks to Punjabi singers and performers, poets and writers, who have elevated their rivers far above the mythical and sacred by transforming them into metaphors for powerful human emotions.

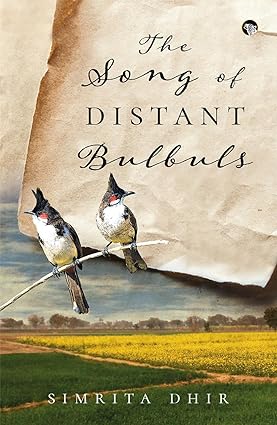

In light of that argument, Simrita Dhir, a young academic from UC San Diego, makes a strong case favoring the former with her second novel, The Song of Distant Bulbuls. It is a poignant love story set on the banks of river Ghaggar, an intermittent river running through the vast arid region bound by two mighty river systems, the Ganga-Jamuna to its east and the Sutlej-Indus on the west. In Dhir’s narrative, the little-known river itself becomes a metaphor for what may seem small and ordinary about Punjab and Punjabiyat at first glance, but in actuality, is all powerful and extraordinary. Not surprisingly, her twin themes, that of love and longing on one hand and separation and remembrance on the other, happen to be two of the most celebrated ones in Punjabi culture and literature.

The story revolves around twenty-three old Sammi, a quintessential Punjabi heroine—strong, unpretentious, and hauntingly beautiful. Though married, she lives with her parents, paternal aunt, and two very elder brothers because her husband, Hari Singh, an officer in the British Indian Army, was summoned to fight in the Second World War soon after their marriage and has been gone for nearly seven years.

Theirs is a typical rural household and life is near idyllic except for the everyday tussle between nostalgia on one hand, and the pragmatic need to move along on the other, something that has divided the family members into two opposing camps. On one side is Sammi, holding steadfastly to the memory of the 21 days that she spent with Hari Singh after their marriage, and the seven emotionally charged letters that he wrote her from the front. She is supported by her eldest sibling, Jasjit, a sensitive man with a heartache of his own, who is away at Patiala, studying for the Indian Civil Service exam.

Pitted against them are Sammi’s other brother Kirpal, and their domineering mother, Bibi. Kirpal is a prototypical Jat Sikh man—bold, enterprising, and brash. Above all, he is clinically practical, whether hankering after new farmlands in far flung Rajputana and UP, or looking to cut his family’s losses and find another husband for his abandoned sister. Bibi is deadly sick, but still strong and manipulative to use her sickness to promote Kirpal’s argument that seven years of waiting is long enough, therefore Saami should be married off to Kirpal’s rich friend and benefactor, Bachan Singh.

Though both sides are equally passionate about their respective stances, there are no villains here. Faith is a force for good. Zulfi is an impoverished Muslim blacksmith, yet his friendship with Jasjit transcends socio-economic, cultural, and religious barriers. Similarly, Hari Singh draws from his Sikh ethos to seek sustenance during the most devastating war in human history. Even the anti-hero, Bachan Singh, has an honorable streak. He seeks forgiveness for committing bae adbi, insolence, immediately after inopportunely declaring his undying love for Saami. “I will wait for you,” he blurts out in remorse, “and never force myself on you.” The real culprits are time, separation, and uncertainty, three villains that must be overcome through patience, sufiana love, and unwavering faith.

If there is one flaw in the novel, it is that at times, the pace seems to stall, for Dhir coerces the reader to pay attention to every scene in its minutest detail, but then it is this very quality that gives her narration a dreamlike nature. Her descriptions of the Punjabi countryside—not only its layout, but its seasons, scents, foliage, and trees are poetic in quality, reminiscent of the great works of Punjabi literature, from Waris Shah’s Heer to Guru Nanak’s Barah Maha. Moreover, Dhir not only describes the characters’ emotions and experiences, but also ties them subtly and beautifully to the surroundings, especially the river Ghaggar, a seasonal river, which is almost always overlooked in comparison to the famous five rivers of Punjab—Sutlej, Beas, Ravi, Jhelum, and Chenab.

The novel presents a metaphor for people and things at risk of being overlooked and forgotten. It is set in Aliwala, a small village located in the backwaters of the Malwa region of Punjab—itself a marginal locus in popular Punjabi psyche and literature. It showcases the everyday life under the princely state of Patiala, and the Indian and Sikh contributions towards the Allied victory in the Second World War. Finally, it pays homage to the steep price paid by the far too often forgotten women on the home front.

The book is thus an important contribution to South Asian English literature by a Punjabi author, highlighting the Punjab that once was—kind, gentle, fraternal, stoic, but above all—good. It is this last quality—goodness—alluded to frequently and unapologetically throughout the novel, that has the potential to leave the reader with an endearing and warm feeling about an uncomplicated time, that once was, before the partition of the nation forever altered the fabric of the place.