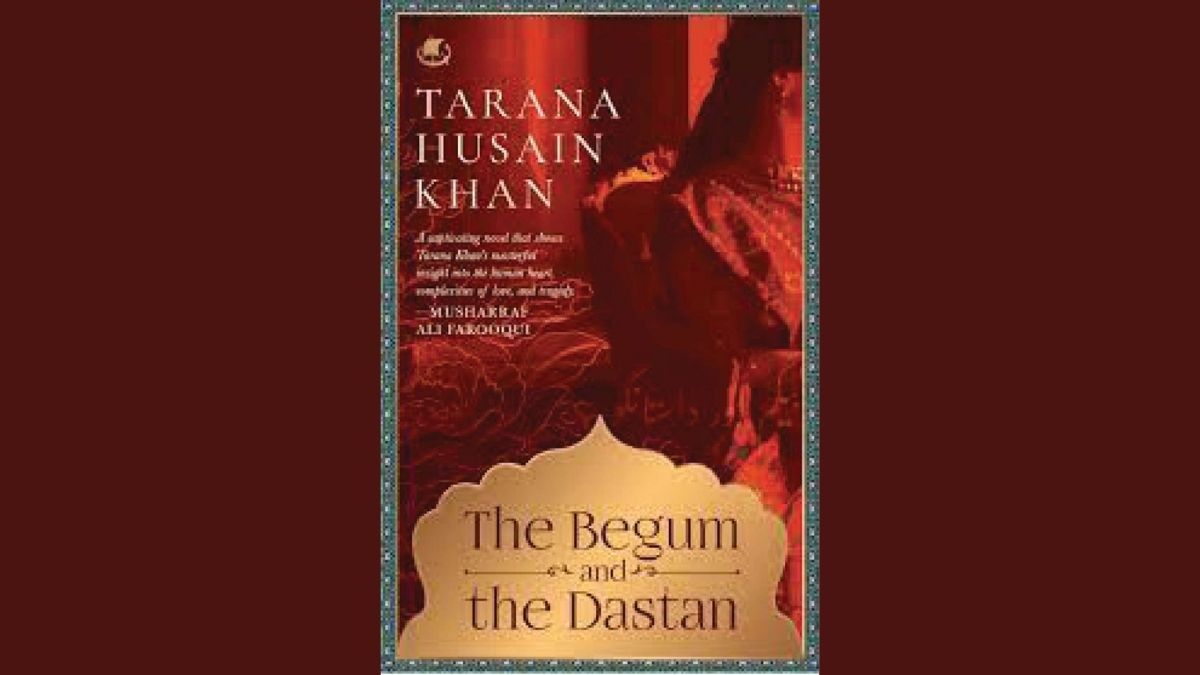

Tarana Husain Khan, whose book The Begum and the Dastan (Tranquebar) goes back to the year 1897, when in the princely state of Sherpur, Feroza Begum, beautiful and wilful, defies her family to attend the sawani celebrations at Nawab Shams Ali Khan’s Benazir Palace. When Feroza is kidnapped and detained in the Nawab’s glittering harem, her husband is forced to divorce her, and her family disowns her. Reluctantly, Feroza marries the Nawab, and is compelled to negotiate the glamour and sordidness of the harem.

This is a book that takes you on a journey. It masterfully develops and conjures the scene, transporting you in time and allowing you to become a part of the lives of its characters.

Dastangoi has its origins in the Persian language. Dastan means a tale; the suffix -goi makes the word mean “to tell a tale”. In the bazaar chowk, Kallan Mirza, a skilled ‘Dastango’, spins a hauntingly familiar tale of a despotic sorcerer, Tareek Jaan, and his grand illusory city, the Tilism-e-Azam, where women are confined in underground basements. As Kallan descends deeper into an opium addiction, the boundaries of fantasy and reality begin to blur.

And in the present day, Ameera listens to Dadi narrating the tale of Feroza Begum, Ameera’s great-grandmother. Confined to her house because her parents haven’t paid her school fees, Ameera takes comfort from Dadi’s story.

As her world disintegrates, she is compelled to ask herself if anything has changed for Sherpur’s women. The author also mentioned a few crude details about child marriage and love slavery.

Inspired by real-life characters and events, The Begum and the Dastan is a haunting tale of a grand city and its women.

The book tells three parallel stories: Feroza Begum’s life; the Dastan, which is full of ‘Aiyyars and Tilisms, Paris and Princes’, and is narrated by a character within Feroza’s story; and the frame story, which takes place in 2016-17 and attributes the tale of Feroza Begum to a young girl being narrated by her grandmother. One of the book’s standout features is the presence of a ‘Sher’ in each chapter.

You’ll really like to know how Feroza lived her life, her ideas and goals, and her death in this brilliantly researched novel. You’ll be amazed at how much emotional involvement the author has made in the ancient tale.

Apparently, since it was intended as a cautionary story for young girls, it makes you feel stifled and vulnerable at the same time.

The 19th century “Nawabi’ culture has been meticulously researched and presented by the author.

If you try to find out about the metamorphosis of Feroza’s character—how she starts to “accept” the circumstances with the Nawab, and if a modern reader would be comfortable with that, Khan asserts in her book that the protagonist’s options were limited by her predicament. She was confined to the Nawab’s harem and her family had abandoned her.

How did a woman in the late nineteenth century deal with such circumstances?

It might be difficult for the “modern” or “feminist” person to understand her actions. Tarana didn’t want Feroza to be a modern woman dressed in ancient clothes. She also didn’t want to project these sensibilities onto Feroza’s character. In fact, she had to restrain herself from putting her words and thoughts into her persona. She belonged to a certain time in history, and her actions and thoughts had to mirror those times.

The prose is beautiful and almost surreal, and the characters shimmer with such excellence that it’s difficult not to admire them.

The author, who has weaved two timelines into the book, insists that at the core of The Begum and the Dastan is the question of patriarchy.

To begin with, Tarana was focused on writing Feroza Begum’s narrative, but because of her first-hand experience, the issue of the plight of the female child in small-town India had been plaguing her.

Ameera, who lives in the present era, wonders if anything has changed for young girls today.

The author wants her readers to ponder something other than Feroza’s predicament. Feroza’s anguish went unnoticed, and life remained hidden beneath the palace’s grandeur and glitter. The suffering of women, patriarchy, and regressive practises intended towards women, which were prevalent in the period, still exist in society now. It’s structured in such a way in the book that you’ll be overwhelmed with feelings and fury.

Patriarchy has an impact on young girls in Indian households by limiting their image of themselves and placing physical limits on them. As a result, Ameera’s existence is a modern counterpart to the life of the veiled Begums and their limited possibilities. This intertwined tale of women who lived in separate eras and universes but whose fates converged in the same way will undoubtedly make you uncomfortable as well as relatable. The author did an excellent job of writing this piece of history, which many were unaware of in a very profound way.

While reading this novel, you will realise that Feroza’s story is not the only one that has disappeared from the pages of history and whose voices inhabit oral history. There have been women who have had an impact on political decisions and cultural developments but are rarely mentioned in cisgender male histories. This book deals with those characters mostly. Unfortunately, not much has changed for women. To make this a complete book, the author has done an incredible job of combining fiction and history with a delicate hand of imagination. The story lives with you long after you have read it.

Dr Tarana Husain Khan is a writer and cultural historian. Her writings on the oral history, culture and the famed cuisine of the erstwhile princely state of Rampur have appeared in prominent publications such as scroll.in, Eaten Magazine, The Wire and in the anthologies Desi Delicacies (Pan Macmillan, India) and Dastarkhwan: Food Writing from South Asia and Diaspora ( Beacon Books, UK). She hosts and curates a website on Rampur culture and oral history. She lives between Rampur and Nainital with her husband.

Ashutosh Kumar Thakur is a Bangalore-based Management Consultant, Literary Critic, and Co-director of the Kalinga Literary Festival. You can reach him at ashutoshbthakur@gmail.com.