A Swedish study published in The BMJ reveals a concerning association between obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and an elevated likelihood of mortality from both natural and unnatural causes compared to individuals without the condition.

The study underscores the importance of addressing preventable natural causes of death among those with OCD, emphasizing the need for enhanced surveillance, proactive prevention measures, and timely interventions. The findings highlight a call to action for comprehensive strategies aimed at reducing the risk of fatal outcomes in individuals living with OCD.

OCD is typically a long-term psychiatric disorder affecting about two per cent of the population. It is characterised by intrusive thoughts, urges or images that trigger high levels of anxiety and other distressing feelings – known as obsessions – that the person tries to neutralise by engaging in repetitive behaviours or rituals – known as compulsions.

OCD is also associated with academic underachievement, poor work prospects, alcohol and substance use disorders, and an increased risk of death.

Previous studies on specific causes of death in OCD have mainly focused on unnatural causes (eg, suicide), but little is known about specific natural causes.

To fill this knowledge gap, researchers set out to estimate the risk of all causes and cause-specific death in people with OCD compared with matched unaffected people from the general population and with their unaffected siblings.

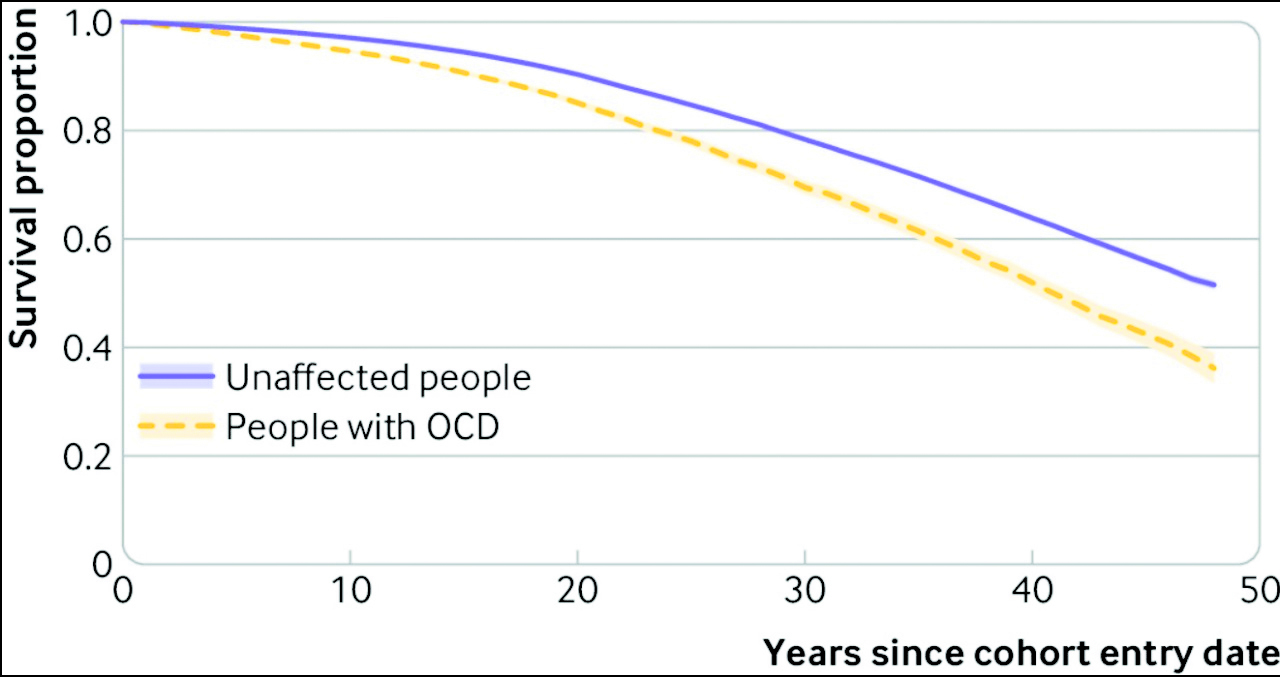

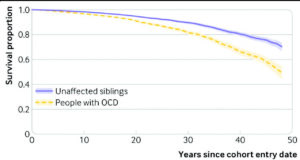

Utilizing data from multiple Swedish population registers, the researchers identified a cohort of 61,378 individuals diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and compared it with a control group of 613,780 individuals without OCD, matched at a ratio of 1:10 based on sex, birth year, and county of residence. Additionally, a sibling group consisting of 34,085 individuals with OCD and 47,874 without OCD was included in the study.

The average age at which OCD was diagnosed was 27 years, and both cohorts were monitored for an average duration of 8 years, spanning from January 1973 to December 2020. Notably, the overall death rate among those with OCD was higher compared to the matched group without OCD, with rates of 8.1 versus 5.1 per 1,000 person-years, respectively.

Upon adjusting for various potentially influential factors including birth year, sex, county, migrant status, education, and family income, individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) exhibited an 82% heightened risk of death from any cause. This excess risk of mortality was more pronounced for both natural causes, with a 31% increased risk, and notably for unnatural causes, where there was a threefold increased risk. Within the realm of natural causes, individuals with OCD faced elevated risks associated with respiratory system diseases (73% increase), mental and behavioural disorders (58% increase), diseases of the genitourinary system (55% increase), endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases (47% increase), diseases of the circulatory system (33% increase), nervous system diseases (21% increase), and diseases of the digestive system (20% increase).

Uniquely, among unnatural causes, the risk of death by suicide exhibited the highest increase (nearly fivefold), followed by accidents with a 92% heightened risk.

The research incorporated full siblings, defined as individuals sharing the same biological parents, into the study if they met specific criteria. These criteria included being singleton births, residing in Sweden between 1973 and 2020 from the age of 6 years onward, and not having received an OCD diagnosis during the study period. To facilitate the linkage between siblings with shared parents, unique family identification numbers were generated, effectively creating family strata with siblings differentially affected by OCD.

In instances where more than one sibling within a family stratum had an OCD diagnosis, one random sibling with OCD was selected, along with all unaffected siblings. The follow-up period for each sibling commenced on January 1, 1973, the date of their 6th birthday, or the date of immigration to Sweden—whichever was the latest—and continued until the date of death, emigration from Sweden, or the conclusion of the study period, depending on the earliest occurrence.

The risk of all-cause death was similar in both women and men, although women with OCD had a higher relative risk of dying due to unnatural causes than men with OCD, likely due to the lower baseline risk among women in the general population, note the researchers.

In contrast, people with OCD had a 10% lower risk of death due to tumours (neoplasms).

This is an observational study, so can’t establish cause and the researchers point out that registry data only includes diagnoses made in specialist care. It’s also unclear whether the findings generalise to other settings with different populations, health systems and medical practices.

Nevertheless, this was a large study based on high-quality national data, and the results remained largely unchanged after further adjustment for psychiatric conditions and family factors, suggesting that they withstand scrutiny.

As such, they conclude: “Non-communicable diseases and external causes of death, including suicides and accidents, were major contributors to the risk of mortality in people with OCD. Better surveillance, prevention, and early intervention strategies should be implemented to reduce the risk of fatal outcomes in people with OCD.”

Non-communicable diseases, alongside external causes of mortality such as suicides and accidents, emerged as significant factors influencing the mortality risk among individuals with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD). It is imperative to advocate for enhanced surveillance mechanisms, implement proactive prevention initiatives, and introduce early intervention strategies.

These measures are pivotal in mitigating the potentially fatal outcomes associated with OCD, underlining the importance of a comprehensive and tailored approach to promote the overall well-being of individuals grappling with this mental health condition.