The most vital concern today is not to lose the advantages gained on the ground at a negotiating table, as it has often happened in the past. So far, nothing has been lost during the seven rounds of border talks conducted in Ladakh, by Lt Gen Harinder Singh, the commander of the Leh-based 14 Corps.

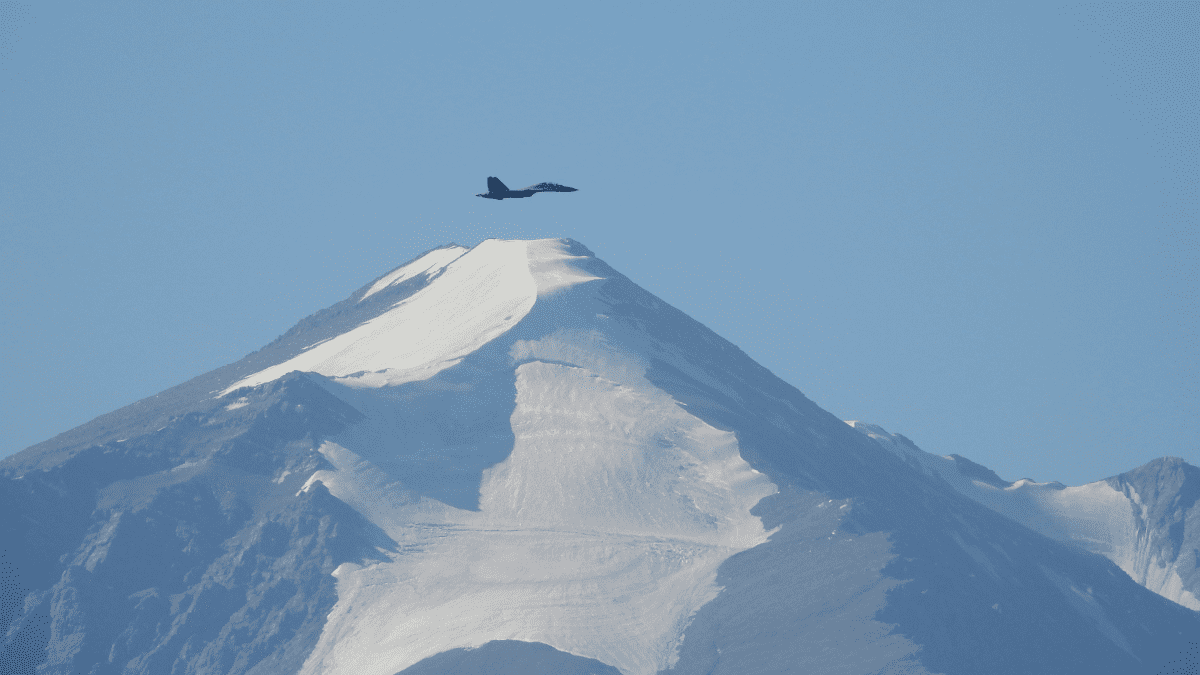

After five months since the beginning of the standoff with China in eastern Ladakh, it is time to draw up a temporary balance sheet of the conflict. Militarily, India’s position changed for the better on the night of 29-30 August, when Tibetan commandos occupied the ridges south of Pangong Lake. It was an important strategic victory, but also a psychological one, showing that the Tibetans are with India in the battle against China’s hegemonic advances.

The most vital concern today is not to lose the advantages gained on the ground at a negotiating table, as it has often happened in the past. So far, nothing has been lost during the seven rounds of border talks conducted in Ladakh, by Lt Gen Harinder Singh, the commander of the Leh-based 14 Corps. However, to have transferred the ‘ground’ negotiation from the Ministry of External Affairs is a victory in itself. In the past, the MEA has often been the weak ‘diplomatic’ link, as the mandarins are often satisfied by simply ‘cutting the apple in two’. The ‘original sin’ of the present situation on the Indian border is due to this particular weakness. While it had been known for years that China was building a road across the Aksai Chin, South Block had kept quiet, probably to not offend Mao and his cohorts.

On 18 October 1958, the then Foreign Secretary had politely written to the Chinese Ambassador that Delhi’s attention had been drawn to the fact that China had built a road “across the eastern part of the Ladakh region of the Jammu Kashmir state, which is part of India. This road seems to form part of the Chinese road known as YehchangGartok or Sinkiang Tibet highway, the completion of which was announced in September 1957.”

The Indian official had complained: “In view of [this], it is matter of surprise and regrets that the Chinese government should have constructed a road through indisputably Indian territory without first obtaining the permission of the Government of India and without even informing the Government of India.” With the danger of such a preposterous reaction looming large over Ladakh, one can only rejoice that the government has involved mainly the Army in the talks. As mentioned in a previous column, it was nevertheless positive that Naveen Srivastava, the MEA Joint Secretary dealing with China, was present in Moldo/Chushul.

Lt Gen P.G. Kamath, a defence analyst (and a ‘thinking general’) recently wrote, “I have always been rubbing the point that the MEA is a relic of the Nehruvian era and is unable to respond to the extremely fluid and dynamic geostrategic imperatives. To make matters worse, we have put a career diplomat in charge of the MEA.” However, the presence of S. Jaishankar, with his ‘chromosomic’ antecedents (his father being one of the sharpest Indian strategists) and his long experience in the Ministry, has definitively brought improvements, though the minister has had to deal with the antiquated work culture and old mindset of an ‘elite’ corps, who has a tendency to think that they know everything.

The problem is compounded by a series of innumerable blunders committed by South Block over the decades — to give a few examples, the Nehru government remaining quiet when the Indian Consulate in Kashgar was closed by China in December 1949, (“we can do nothing about it, the times have changed”); the weak protests made when Tibet was invaded 70 years ago; and, in 1954, the Panchsheel Agreement not only giving away the Indian rights in Tibet to China, (which included military escorts), but worse, the border issue not even being brought to the table, with the consequences that we see today in Ladakh. The first three ‘principles’ promised “mutual respect for each other’s territorial integrity and sovereignty”, “mutual non-aggression”, and mutual non-interference in each other’s internal affairs.” By accepting that Tibet belonged to China, India could no longer claim her genuine interests in Tibet. Today, what makes things more complicated is that the Indian diplomacy accepted the concept of a Line of Actual Control (LAC) which has never existed on a map or on the ground.

The recent blitzkrieg from Beijing about a November 1959 LAC is pure Information Warfare (IW) using some gullible Indian newspapers. Where is the Line that Zhou Enlai mentioned on 7 November 1959 to Nehru? Is there a map? On what is it based — on a clearly-defined watershed, on customary rights of the local grazers, on land or house taxations? No, it is pure Chinese bluff. But there is worse: the MEA has inked several agreements with China, forgetting to define the main object of the accords — the LAC. It is hard to believe that Delhi signed on the dotted line without any definition or map of the LAC, leaving sufficient space to Beijing to change the posts. On 7 September 1993, India and China entered into an agreement “in accordance with the Five Principles” which speak of the “Maintenance of Peace and Tranquility along the LAC,” but nowhere is the LAC itself defined, though it says, “… pending an ultimate solution to the boundary question… the two sides shall strictly respect and observe the LAC between the two sides.” It is truly amazing, but there is no map of the LAC in the Western Sector even today.

Then, on 29 November 1996, an agreement “on Confidences Building Measures in the Military Field along the LAC” was negotiated, “believing that it serves the fundamental interests of the peoples of India and China to foster a long-term goodneighbourly relationship in accordance with the five principles.” Both parties were “convinced that the maintenance of peace and tranquility along the LAC in the India-China border areas accords with the fundamental interests of the two peoples.” Yet again, the LAC was not defined or delineated. In 2000, both sides agreed that they would initiate a process for the clarification and determination of the LAC in all sectors of the boundary.

A meeting took place in March 2000, where maps of the middle sector were exchanged. On 17 June 2002, both sides met again and maps of the Western Sector were seen by both sides for about 20 minutes, before the Chinese withdrew their maps. Ten years later, in January 2012, there was still no map when both sides established “a Working Mechanism for Consultation and Coordination” which mentioned a non-existent LAC: “Firmly believing that respecting and abiding by the LAC pending a resolution of the Boundary Question between the two countries.” Then, on 23 October 2013, an official accord acknowledged “the need to continue to maintain peace, stability and tranquility along the LAC in the India-China border areas and to continue implementing confidence building measures in the military field along the Line of Actual Control.” It spoke in particular of “flag meetings or border personnel meetings at designated places along the LAC.” But where is this LAC? This time, the Indian Army will make sure that China does not escape without the proper definition of a line that the Indian jawans can defend. The nation has its fingers crossed.

The writer is a French-born author, journalist, historian, Tibetologist and China expert. The views expressed are personal.