It is in this atmosphere — the air filled with irreverence to caste and class hierarchy that Shivaji Rao Gaekwad entered Tamil films — with his anti-hero image, nonchalance, defiance of authority, and rakish smile.

Again, it was Bhaskar Rao who predicted during those uncertain first years that Rajinikanth would become a superstar. He had written a review of Katha Sangama. The piece had been short and needed four more lines to fill it out. Bhaskar Rao hastily added what came to him. He wrote, ‘Here is an actor with such talent that it should not surprise anyone if he becomes a superstar one day.

Actors who were baffled at the way he stormed the field could only attribute it to ‘sheer luck’ or the fact that he was ‘blessed’. Rajini was lucky in a sense. His arrival coincided with a massive change that the Tamil film industry was undergoing in terms of production, content, and storytelling. Tamil commercial cinema was dominated by MGR (who also belonged to the DMK), Sivaji Ganesan, Gemini Ganesan, Jaishankar, and such others. From the 1950s till the early 70s, films that projected the resurgent Dravidian symbolisms and party ideologies with melodramatic acting and theatrical textual Tamil scripts dominated the scene. The Dravidian Movement used films and film songs sung and acted by MGR, the hero, to take its ideologies to the masses. The audience lapped it all up during the period that was charged with and inspired by revolutionary ideals. MGR always played the do-gooder, a protector of damsels in distress, a non-smoker, and a non-drinker. His promoters envisaged his characterization with a view to projecting him as a future chief minister of Tamil Nadu. He became a symbol for the party. MGR fan clubs were created to muster votes.

The DMK came to power in 1967, and later when the DMK split and MGR formed his own party, AIADMK, in 1974, there was no longer any need to use cinema to take the ideology to the masses. Veteran actors MGR and Sivaji had outgrown their romantic hero roles. Even their most ardent fans were tired of the same old plots with heroes giving sermons about good behaviour.

By the time Balachander came on the scene, the cinema-going public was ready for a whiff of fresh air. Balachander was born into a Brahmin family in Nannilam, a small town in Thiruvarur district. He completed his graduation and joined the Accountant General’s office in Madras as a clerk. A theatre enthusiast, he had been writing plays with themes that interested the middle class. He was not part of the Dravidian movement. The movement had empowered the backward classes. And now a vibrant middle class, aware of equal rights and gender issues, was ready for a conscious questioning of traditional mores and values. Balachander was able to capture the shifting mood of the audience and write plays that spoke to them. His characters were bold, irreverent, and asked pertinent questions. The dark actor was not always the villain and the fair one was not an angel. There was no age taboo for love. He painted prostitutes as prisoners of circumstances and not as social outcasts. The woman was no longer just the loyal faithful wife who did not cross the threshold of her house. His plays were huge draws and when he ventured into cinema, his films were box office hits.

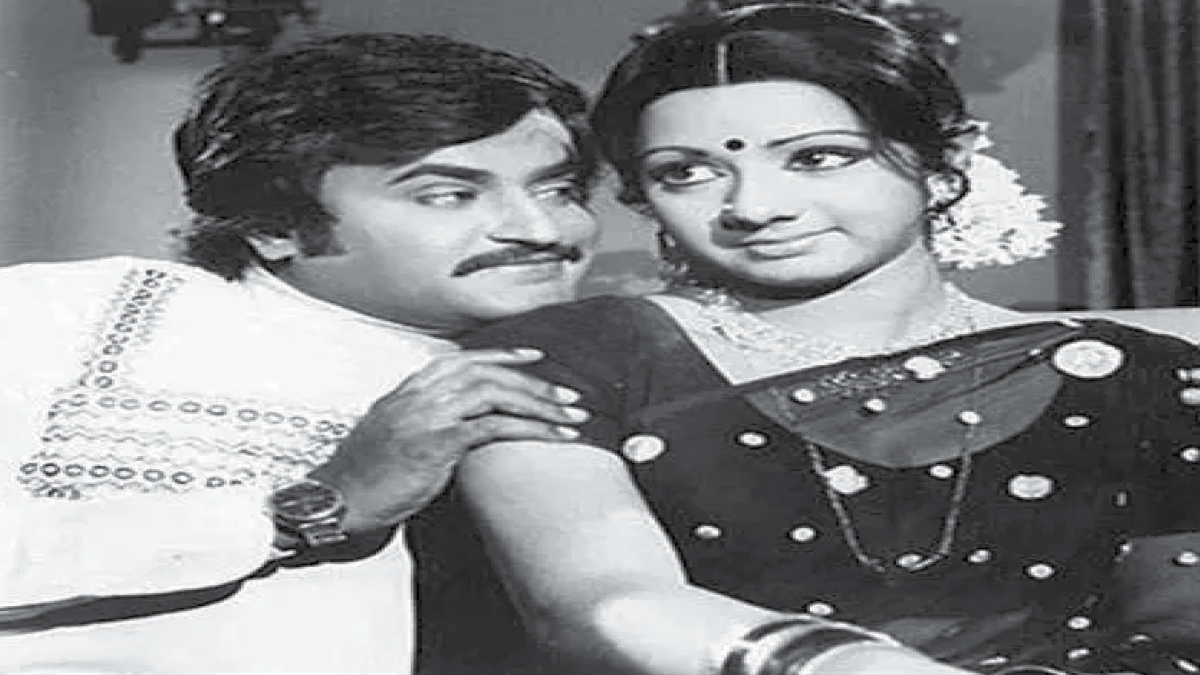

It was at this time that music maestro Ilaiyaraaja and director P. Bharathiraja also entered Tamil films. They set new trends in music composition and storytelling respectively. Bharathiraja shifted the lens outside the studios and set his stories in the countryside. Theatrical dialogue backed by ideological underpinnings was replaced by colloquial banter. For the first time, the urban audience could smell the freshness of the village air and hear the chirping of the birds. This is when Rajinikanth entered. His entry marked a clear break from the conventional fair-skinned hero who was a paragon of virtue. Rajinikanth was dark, he smoked and drank on-screen, and could play dark characters and get away with it. His rawness and irreverence made him a hero of the subaltern.

Sadanand Menon says, ‘With Rajini, Tamil cinema, and by extension, Tamil society learnt to be kosher with being “bad”. It was no longer something that someone was going to make them feel guilty about. Rajini taught Tamil society to abandon platitudes about Rama as maryada purushottam and accept the possibility of a Ravana or a Duryodhana actually being good. When Rajini stared directly back into the camera…and hissed out the lines from the corner of his mouth, executed his side-winded walk of electric energy, tossing his tousled hair, he became the new and manifest example of hitherto suppressed expressions of desire, no matter how risky or preposterous it seemed.’

The most conspicuous difference that the audience saw in Rajinikanth was his unbridled energy. After that initial lull, Balachander cast him in three films: Anthuleni Katha (Telugu, 1976), Moondru Mudichu (1976), and Avargal (1977) in quick succession. It ensured that the film-going public didn’t forget him. In the year 1977, Rajinikanth acted in fifteen films, and didn’t play the hero’s role in all of them. Unlike other actors, Rajinikanth enjoyed playing the villain and stole the show with his off-beat portrayals of these dark characters. All the films were hits and Rajini began to be considered lucky by producers.

Y. G. Mahendran got to know Rajini well when they worked together on the Tamil film Bhuvana Oru Kelvi Kuri (1977), directed by reputed director S. P. Muthuraman. Mahendran found that Rajini was an intense person who did not speak much. He was very respectful to his seniors—even to Mahendran, who was a senior in the profession, and also because he was the son of his former principal. Mahendran noticed that Rajini would listen carefully to suggestions given by everyone, but he would take only what he thought was right for him. He knew right from the beginning that he could survive in the field only if he stood out. Mahendran remembers how an experienced senior actor, P. Sivakumar, tried to coach him on how to deliver a line. Rajini listened and nodded, but finally delivered the line in his own style. ‘People think he is a director’s actor, but he often went beyond the brief. Muthuraman allowed him the freedom. That is why the pair clicked so well.’

Muthuraman has been associated with the legendary AVM Studios that has produced over 170 films in Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, and Hindi since 1955. He started there as an assistant in the editing department and went on to become a successful film director. Sitting in his modest office room at the AVM Studios compound, he remembers his reaction when he first saw Rajinikanth on the screen in a villain’s role. Actors who played the villain followed a set formula—they had a loud, sinister laugh, rolled their eyes, and gritted their teeth. But Rajini played it very differently and with a style that had not been seen. Muthuraman was impressed. When it came to casting Rajinikanth for Bhuvana Oru Kelvi Kuri, he cast him for the hero’s part made Sivakumar the villain. He was convinced that Rajinikanth was capable of bringing something unique to the character. The two main characters were not straightforward—the one who came across as the villain was, in fact, the good guy while the one who seemed to be the hero was the villain. Muthuraman felt that making Rajinikanth appear to be the good guy would ensure that the audience would be surprised. Sivakumar, who had always played the good guy, was disappointed when he came to know that he would be playing the villain. But Muthuraman convinced him that it would work. The film became a box office hit.

‘Mind you, at that time, Rajinikanth was not able to speak two sentences at a stretch in Tamil,’ laughs Muthuraman. Rajinikanth was a little nervous when he saw that he had to speak lengthy dialogues in the film. Muthuraman put him at ease, telling him to prepare as much as he could and then act in his own style. This freedom and belief that the director showed in him allowed Rajini to reach ‘the next level’ in his acting career. Muthuraman believes that if A. V. M. Chettiar (founder of AVM Productions) had been alive, he would not have accepted Rajinikanth, because Chettiar demanded perfect rendering of Tamil. But it was Rajinikanth’s Kannada-tinged Tamil and the speed with which he delivered his lines that became a style statement. Muthuraman and Rajinikanth worked together in twenty-five films, with Rajinikanth playing a variety of characters. Bhuvana Oru Kelvi Kuri was not only a commercial hit, Rajini’s acting in it also received critical acclaim.

Sivakumar’s friends felt that he should not have agreed to take on the villain’s role. But ‘it was destiny’, he says. ‘I told them so. Rajinikanth was destined to shoot up in popularity due to that role. No power on earth could have changed that.’ But it was not sheer luck or divine grace that was the reason for his success, says Muthuraman. It was hard work and total involvement in the work he did. Unless he had absorbed the story completely and internalized it, he would not act. His popularity was the direct result of his dedication to the craft.

Muthuraman admits that directors like him did indeed include songs and scenarios that they knew would appeal to the fans— the speed and unique gestures. Unlike in earlier years, this was not done to curate his image. Instead, it catered to aspects of Rajini’s persona that the filmmakers knew the fans loved. The 1980 film Murattu Kaalai directed by Muthuraman had a song with these lyrics:

“Pothuvaa en manasu thangam, aana oru pottiyinnu vanthuvitta singam” (Usually my heart is like gold but when there is a contest it becomes fierce as a lion)

And in the 1989 film Raja Chinna Roja had this: “Superstar yaarunnu ketta kuzhanthaiyum sollum” (If you ask: ‘who is the superstar?’, even a child will tell you)

Once when the cast and crew were driving to a location for an outdoor shoot, a group of schoolchildren from Classes V to XII blocked the road, forcing the vehicles to stop. ‘They had come to know that Rajinikanth would be in that group. “Stop the vehicle, we want to see Rajinikanth!” they shouted. Such was his appeal. He had caught the imagination of children as young as six.’

Rajini’s fans would request the theatre manager to play the songs again and again. This was very different from MGR’s popularity. MGR’s image was built very carefully and systematically as a viable political leader. Rajini had no political ambitions when he first entered films. He wanted to work as much as he could, act in as many films as possible, take every opportunity that came his way and make money. He began working non-stop. The recognition that came early in his career was intoxicating, blinding. He worked like one possessed. Work became an obsession. A disease, an affliction…till the mind went berserk.

The excerpt is from the book ‘Rajinikanth: A Life’ (published by Aleph Book Company).