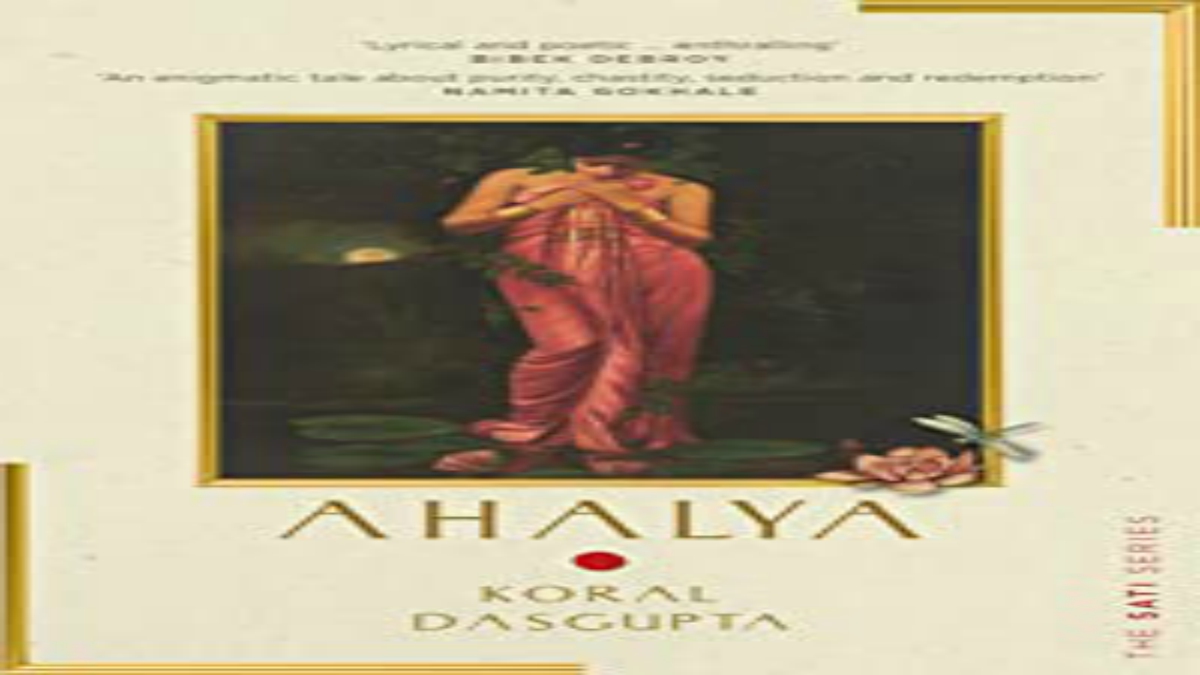

Who was Ahalya? A young, beautiful woman who has just woken up to herself with all consciousness — how do you expect her to react when she knows she’ll be married off to a sage, Gautam? A sage practising penance is suddenly been imposed with the responsibility of domesticity — what should be his dharma? To what extent are you willing to travel for the happiness of your spouse? And what if your happiness is a threat to that of your spouse’s? The philosophical response to these questions would be elaborated in Ahalya: The Sati Series, says author Koral Dasgupta.

The author intended to put forth how she perceived Ahalya and weaved the mythological fiction while keeping her story’s basic framework intact. What we know of Ahalya through the Ramayana is that she was cursed by her husband for indulging in a physical relationship with Indra. Although there have been many explanations of her infidelity and the curse, Koral has touched upon and delved into the details of her course of life and not just the striking parts.

Excerpts:

Q. Beauty has been a fascinating element in Indian mythology and your work puts forth an honest perspective of an alleged minor character in mythology who was wronged. While retelling her story, how did you want to project Ahalya?

A. I have zoomed out Ahalya’s small episode from the vast Ramayana. The epics are philosophical texts where no one is there by fluke. Every character, every episode — small or large — is metaphoric and metaphors are subject to interpretations. So, anyone else’s ‘relationship’ with Ahalya could be very different from what I have felt. The epics have outlined the Pancha Kanya as the epitome of great spiritual strength and I could see why. My understanding of Ahalya is that of a woman who used her spiritual and sexual strength to attain what she felt was right for her, over what the world felt was right for her.

Q. Having explored the protagonist in depth, do you believe this book can lead to a shift in perspective about Ahalya?

A. When I started writing Ahalya, I had no such goal or agenda. I just wanted to pour my best in recreating the story without disturbing its original framework. Now that I have written it, and audience response is overwhelming, several thoughts strike me. One of them is, if the mythological women are reintroduced to the audience with the mystic language that they deserve, people would perhaps rethink on the way Indian women have been traditionally defined. If that is a possibility, then I am happy to work harder to experiment more with the beauty of language and storytelling.

Q. What sort of research you did for Ahalya: The Sati Series?

A. During the writing of this text, I have consciously tried not to be a hardcore researcher and attempted to be a liberated interpreter. Not too much is revealed about Ahalya, her story in the Ramayana was included to introduce Ram in all his glory. To understand the godliness of Ram, Ahalya sends a very strong message which has been explained in the book. Otherwise, I had a few known dots to connect and have taken every liberty to sow seeds of my choice between each dot.

Q. According to you, what might have happened between Ahalya and Gautam before she was turned into stone as the various modern retellings have presented their reasonings?

A. The book provides an alternate explanation to Ahalya’s ‘infidelity’ and also her curse. Women are change agents and Ahalya identifies her as one. She is pleasant, she is the most tranquil form of a rebel, she is overpowering. By the end of the story, she gets a part of everything she ever wanted. And the remaining, she knew she could never get. The curse stands as a metaphoric wall between her aspirations and her realisations.

Q. What are the takeaways for young women readers in Ahalya: The Sati Series?

A.In every era, intellectuals are faced with existential questions like who am I and where do I come from. The question is even more haunting for the woman because the social and cultural distinctions in gender are becoming more and more prominent as we are getting increasingly conscious of our sexuality, trying to express ourselves fearlessly and unapologetically. The impression we carry of our past shapes our future. The Sati Series will give wings to those impressions, introducing India as the mystic land with sensuous legends that were spiritually active, neither dominated nor intimidated by impositions of patriarchy. This should inspire and lend strength to the youth today — not just women.

Q. What intrigued you to revisit Indian mythology from a feminine perspective in the Sati Series, and particularly start off with Ahalya? What can we expect from the forthcoming works?

A. The word “Panch Kanya” has been translated by scholars as “Five Virgins”. How on earth do you explain Ahalya, Kunti or Draupadi as a virgin or kanya? These ancient texts had answered what we debate today as feminist ideologues. The epics had emphasised that it is the purity of the soul that matters; the body is only a temporary framework. This itself was something worth exploring and I am glad to have tried it. In the forthcoming works, the audience might find very different women in Kunti, Draupadi, Mandodari, Tara — from the clues that popular literature has ignored. Not many people know that Kunti was a great mathematician and scholar. Let’s leave it at that.