While ruling rationally on a very significant aspect of preventive detention, the Kerala High Court in a most learned, laudable, landmark and latest judgment titled Luciya Francis vs State of Kerala & Ors cited in Neutral Citation: 2023:Ker:45104 and as we see it is read as W.P.(Crl).No.666/2023 while dealing with a writ petition has held most explicitly that the preventive detention law cannot be used as a punitive measure and as a substitute of criminal trial. We must note that a Division Bench comprising of Hon’ble Mr Justice A Muhamed Mustaque and Hon’ble Mr Justice Sophy Thomas observed in no uncertain terms that, “The preventive detention law cannot be used as a punitive measure and as a substitute of criminal trial. What cannot be achieved through a trial cannot be achieved through preventive detention. It can be invoked only for maintenance of public order when activities of a person become threat or adverse to the society.” The Bench said that any aberration of an individual in the form of commission or omission may attract penal law which may also result in law and order but not necessarily action need to border on public order. The High Court thus we see concluded that the detention order is illegal. Accordingly, it disposed of the writ petition and directed that the detenue shall be released forthwith.

At the very outset, this brief, brilliant, bold and balanced judgment authored by Hon’ble Mr Justice A Muhamed Mustaque for a Division Bench of the Kerala High Court comprising of himself and Hon’ble Mrs Justice Sophy Thomas sets the ball in motion by first and foremost putting forth in para 1 that, “This writ petition is at the instance of the mother of George Francis, who has been detained pursuant to an order passed under the Kerala Anti-Social Activities (Prevention) Act, 2007 [hereinafter referred to as the “KAA(P)A”]. The detenue has been detained classifying him as a known goonda, as referable under Section 2(oi) of the KAA(P)A. Section 2(oi) defines ‘known goonda’ as follows:

(o) “known goonda” means a goonda who had been, for acts done within the previous seven years as calculated

from the date of the order imposing any restriction or detention under this Act,-

(i) found guilty, by a competent court or authority at least once for an offence within the meaning of the term ‘goonda’ as defined in clause (j) of section 2.

It would be instructive to note that the Division Bench notes in para 2 that, “The learned counsel for the petitioner, referring to Section 2(i) read with Section 2(j) argues that the detenue cannot be either treated as a drug offender or as a gunda within the statutory provisions as above. It is appropriate to refer Sections 2(i) and 2(j) which reads thus:

(i) “drug-offender” means a person who illegally cultivates, manufactures, stocks, transports, sells or distributes any drug in contravention of the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985 (Central Act 61 of 1985) or in contravention of any other law for the time being in force, or who knowingly does anything abetting or facilitating any such activity;

(j) “goonda” means a person who indulges in any anti-social activity or promotes or abets any illegal activity which are harmful for the maintenance of the public order directly or indirectly and includes a bootlegger, a counterfeiter, a depredator of environment, a digital data and copy right pirate, a drug offender, a hawala racketeer, an hired ruffian, rowdy, an immoral traffic offender, a loan shark [a money chain offender] or a property grabber;”

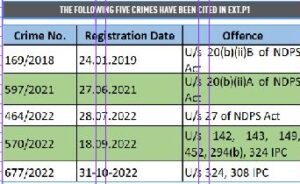

As we see, the Division Bench mentions in para 3 that, “According to the petitioner, the offences enlisted as Nos.2 and 3 are petty offences and he was sentenced to pay fine of Rs.2000/- and Rs.1000/- respectively. It is further submitted that in respect of the offence enlisted as No.1, no final report was filed even after the lapse of more than 4 years. It is further submitted that in respect of offence No.4, the detenue and the defacto complainant compromised and based on the compromise, the detenue was enlarged on bail.”

Do note, the Division Bench notes in para 5 that, “The KAA(P)A being a preventive detention law, the same has to be strictly construed (see the judgment of Apex Court in Prakash Chandra Yadav @ Mungeri Yadav v. The State of Jharkhand & Ors. {CIVIL APPEAL NO. 4324 OF 2023}.”

Simply put, the Bench states in para 6 that, “The Full Bench of this Court in Stenny Aleyamma Saju’s case (supra) after referring to the object of the KAA(P)A enactment opined as follows:

The detention in all preventive detention matters is not based on guilt of the detenue, but on the basis of strong suspicion to have indulged in objectionable activities which affect the society/nation at large. In other words, there is black and white difference between ‘punitive detention’ and ‘preventive detention’; the former being a proceeding by way of imposition of punishment for the offence already committed by the accused; whereas in the case of the latter, it is only to prevent occurrence of any such act which is recorded as possible by virtue of the past conduct of the detenue. In the case of preventive detention, the mischief is more against the society at large, adversely affecting the ‘public order’, which is at a much higher pedestal than the pedestal occupied by the ‘law and order’ situation. By way of ‘punitive detention’, the undesirable consequences which have already been resulted [by virtue of commission of offence] cannot be ruled out and the sentence is only to punish the guilty and to send a message as to consequences to the public at large. But in the case of ‘preventive detention’, the probable damage to be caused is of much more magnitude, as it is likely to affect the ‘public order’ and hence the law makers have consciously decided to take preventive measures rather than cure, thus giving rise to such Statute to abate the possible repetition/recurrence of adverse act/offence and the consequence.”

Quite pertinently, the Bench observes in para 7 that, “The Court cannot remain unmindful of the criminal activity of the detenue, at the same time the detention laws have to be narrowly construed. The impact of the sentence imposed qua public order is an essential element for consideration by the detention authority.”

While citing the relevant case laws, the Bench envisages in para 8 that, “The Apex Court in Ram Manohar Lohia v. State of Bihar [AIR 1966 SC 740] referred to ‘public order’ as follows:

“The contravention of law always affects order but before it can be said to affect public order, it must affect the community or the public at large.”

In Supdt., Central Prison v. Dr Ram Manohar Lohia, [AIR 1960 SC 633] also the Apex Court interpreted public order as follows:

“Public order” is synonymous with public safety and tranquillity : it is the absence of disorder involving breaches of local significance in contradistinction to national upheavals, such as revolution, civil strife, war, affecting the security of the State.””

Most forthrightly, the Bench enunciates in para 9 that, “The generalization of the crime and its impact on the society at large though may not be valid but will be relevant when it relates to a particular crime committed by the detenue. The sentences imposed have to be taken into account with reference to the particular nature of the crime committed by the detenue. If the individual cases highlighted do not disclose any relation to the ‘public order’ contemplated to be secured by such detention order, the detention will become illegal. Mere possession of a narcotic substance cannot be construed as part of stock unless it is manifested with evidence of intention to sell. One might have kept such substances for personal use. The word “stocks” occurring in section 2(i) must be in such a nature kept in possession not for personal use. If any element of commercial motive surfaces, no doubt such “stocks” shall be classified as acts affecting public order. The detaining authority is bound to examine the nature of offences in relation to the public order while passing detention orders. The sentence or the nature of the sentence suffered becomes decisive vis-a-vis the public order. Any aberration of an individual in the form of commission or omission may attract penal law which may also result in law and order but not necessarily action need to border on public order.”

Finally and far most significantly, the Division Bench concludes by holding in para 10 that, “The preventive detention law cannot be used as a punitive measure and as a substitute of criminal trial. What cannot be achieved through a trial cannot be achieved through preventive detention. It can be invoked only for maintenance of public order when activities of a person become threat or adverse to the society. The detaining authority failed to address the issue keeping the perspective of the objectives to be secured under the KAA(P)A. In such circumstances, we order that the detention order is illegal and the detenue is set at liberty. He shall be released forthwith. The Writ Petition (Crl). is disposed of as above.”

In a nutshell, the Kerala High Court has thus made it indubitably clear that preventive detention cannot be used as a punitive measure and as a substitute of criminal trial as it directly violates Article 21 of Constitution which guarantees right to life and personal liberty. There is certainly no cogent reason as to why the men in police uniform, investigating agencies and so also all the courts in India should not abide in totality by what the Kerala High Court has held so commendably in this leading case while releasing the detenue as the detention order is itself illegal as mentioned hereinabove! Let there be no doubt on this!