The temple of Lord Viswambhara has a special festive air on certain evenings. Hundreds of oil lamps light up in the niches in the walls and a Kathakali troupe gathers on the open-air stage for a performance. They pay obeisance to the temple’s deity, an incarnation of Lord Vishnu worshipped as Dhanwantari, the Hindu God for medicine. The shrine is situated on the premises of Arya Vaidya Sala, Kotakkal, Kerala, one of India’s oldest Ayurveda hospitals. Even though the temple is relatively new — established in 1932 by Arya Vaidya Sala’s founder P.S. Varier — and is a private place of worship, it observes strict rituals in accordance with the scriptures. It has also continued the tradition of patronising and propagating cultural arts through the dance and music recitals held on religious occasions. The temple, in fact, holds a seven-day annual festival which attracts both connoisseurs and enthusiasts from all over India to Kottakkal.

We often read about the role of Hindu temples in artistic and intellectual pursuits and this small temple tucked away in one corner of northern Kerala serves as a contemporary example of the part temples play in nurturing and retaining cultural traditions.

At AVS, the temple festival is just one aspect of the concerted effort towards supporting the classical arts. Natyasangham, a centre for performing and teach- ing Kathakali, the classical dance-drama form of Kerala, was established by Varier in 1939. Natyasangham’s teachers and students have not only performed at the temple but, over the years, led the renaissance of this art form by producing talented dancers who have travelled widely and performed in shows both in India and abroad.

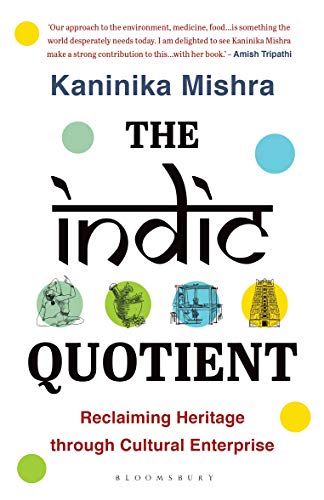

Other recent attempts that aim to revitalise Hindu temples include the revival of its social character as a community centre. During the research for my book, The Indic Quotient: Reclaiming Heritage through Cultural Enterprise, I came across a group of committed individuals in Bengaluru who have, over the past few years, organised a successful annual festival in the city’s temples. The week-long celebration includes dance and music recitals, theatre, puppetry and spiritual discourses. To ensure that the festival does not remain a purely intellectual activity limited to artists and art-lovers, the organisers have used innovative ideas to draw in the local community. They have held storytelling workshops for children, quizzes on Puranic stories and put up a gallery for amateur artists to display photographs, art- work and poetry.

Historical records, through the times, show that Hindu temples have supported various other institutions and vocations. Hand-woven textiles, for instance, flourished because of patronage by both temples and royal families. The deities in the frescoes of the Ajanta cave temples in Maharashtra, which date back to the 7th century, seem to be wearing clothes that resemble ikat patterns. Details of the sacred textiles used for adorning deities or as temple offerings remains undocumented. However, some, such as the block prints from Sanganer in Rajasthan that were used to drape temple idols and Odisha’s Pipli appliqué which was traditionally used in making canopies, seats and ritual dresses for the deities, have found a wide market and been fashioned into bedspreads, table cloths and a variety of other items.

During my travels, while writing The Indic Quotient, I also discovered that Hindu temples were not just consumers of textiles and crafts but were also centres for the fine arts. Tanjore paintings which decorate the walls of the Chola period temples in Tamil Nadu’s Thanjavur or the Pichwai religious scroll paintings in the Shrinathji temple in Nathdwara near Udaipur indicate a sophisticated culture of visual arts.

Nathdwara’s Shrinathji is a manifestation of Lord Krishna and the town is the most important pilgrimage for followers of the Pushtimarg sampradaya, a sub- tradition within the Hindu Vaishnava denomination. The history of the town goes back to the 17th century when the idol was brought here from Vrindavan to protect it from destruction by Mughal ruler Aurangzeb. The art of Pichwai paintings is believed to have originated around the same time. The paintings have an intricate style and portray tales from Lord Krishna’s life. Primarily used as a backdrop behind idols, they have taken on numerous forms today.

The town’s economy and the Pichwai paintings flourish because of the steady inflow of affluent pilgrims. The temple receives generous endowments from devotees and the commercial activity around the temple sustains the traditional artists who live and create their art in Nathdwara. In the last few years, there has been a new interest in Pichwai. Artists are curating exhibitions of antique Pichwai paintings and designers and entrepreneurs are commissioning Pichwai artists to create custom-made sarees and high-end curios.

The beauty of Pichwai lies in its celebration of nature and its beauty with its depiction of lotuses in bloom, kadamba trees, dreamy cow- herds, dancing peacocks and monsoon skies. The clean colours and vivid imagery evoke joyfulness and wholeness which is a central theme in Hindu spirituality. No religion, perhaps, lays as much emphasis on the divine in nature as Hinduism does.

A culture that reveres all creation finds a way to safe- guard them. Hindu temples located along the course of rivers often accord divine status to the creatures that live around them. Ignored and ridiculed as superstition for long, this environmental facet of Hindu temples is now recognised by ecologists and is being used in conservation efforts. Religious beliefs aid protection and sustain biodiversity. Furthermore, the devotees develop emotional bonds with the creatures, which in turn ensure continued efforts to preserve them.

The Hayagriva Madhava Temple in Assam shows how the spiritual can be leveraged for tangible results on the ground. The temple has been able to work together with an environmental group and the government forest department to protect the black softshell turtle or Nilssonia nigricans. The black softs-hell turtle, endemic to the Northeast and Bangladesh, was classified as an extinct species of the wild in 2002 by the Switzerland-based IUCN. A few years ago, a small population of these turtles was found in sacred temple ponds in Assam. This gave conservationists the hope to revive the species in the Northeast.

Freshwater turtles were once aplenty in Assam. The loss of their habitat due to urbanisation and killing for meat led to a massive depletion in their population. The temples have provided them with a safe sanctuary since ancient times. The pukhuris, ponds or ancient tanks commissioned under royal patronage, built alongside temples in Assam have religious sanctions that prohibit the killing of creatures living in them. Used for ritual bathing and drinking, these historical reservoirs have, over the years, become hotspots for rich forms of biodiversity, especially turtles. The Hayagriva Madhava Temple pond is now being used to aid in a mission to reintroduce the species into the wild.

Despite their positive impact on the surroundings, temple conservation has unfortunately been viewed in the narrow terms of religious fundamentalism. Hindu temples address the physical, material, ecological and spiritual needs of communities around it. The revival of a temple revitalises social, economic and cultural activity. The restoration of a temple and its traditions, in fact, rejuvenates every living creature in its vicinity.

Kaninika Mishra is author of the book, ‘The Indic Quotient’ (Bloomsbury India).