The difference between parody and satire has not been accepted or developed by the Indian courts in the context of IP laws. This means that whether a work is a parody or a satire, the defence of fair use can be claimed by the defendants and the work shall also be entitled to claim separate copyright protection as well.

Parody refers to a work that humorously and critically comments on existing work to expose the flaws of the original work. Parody, as a means of criticism, has been historically used by various people such as stand-up comedians, YouTubers, Bloggers, actors, authors, etc. to communicate a particular message or a point of view to their audience. This means that to create a successful parody, one has to, inevitably, use the original work. Since copyright law gives authors of original work certain exclusive rights, such as the right to reproduction, communication to the public, distribution rights, right to make derivative works, and other such rights associated with the work, parody turns out to be a violation of the rights granted to the copyright owner.

The rights that a work of parody might therefore violate are the distribution rights over the work, right to publicize the work in a positive light, and the moral rights which are associated with the author. Moral rights essentially prohibit modification of the copyrighted work in a manner that injures the honor and reputation of the owner of the work.

Parody issues generally come into play with tort law as well as criminal law, especially law on defamation. However, in this article, we’ll try and focus on the major IP issues that hover around the debate regarding parody.

Copyright Law and its philosophy

Copyright is a unique kind of property. Just like other Intellectual property, you cannot touch or feel it, but you certainly can protect the ‘creation of the mind’. However, the objective behind copyright law is to “strike a fine balance between monopolistic claims made by authors of original work and adequate protection to the Intellectual property to encourage further creative thought”. Such copyrighted work can therefore be used by third parties to encourage creativity – This is fair use. However, such use has to be reasonable and under certain conditions for specific purposes only.

The Four Factor Test

For a valid fair use claim, the defendant will have to satisfy what is commonly known as the “Four Factor Test”. Under the four-factor test, the consideration is: firstly, what was the purpose and character of your use of the copyrighted work. Secondly, the nature of the copyrighted work, which means that if the work is copyrighted then, what is the degree of protection that it deserves. Thirdly, the amount and substantiality of the portion of the work that was taken by you. This means that whether the amount of copying done by you was reasonable in relation to the purpose of copying and lastly, the effect that your use will have on the market of the owner. Will your use impact the potential market of the original work.

Parody and Satire

Indian laws treat parody and satire as one and the same. However, the position is different when one looks at the jurisprudence evolved by the courts of foreign Jurisdictions.

In the United States, the courts have differentiated parody and satire to the extent that it impacts the defense of Fair Use under their copyright law. In Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc (1994), the court differentiated between the two and held that “Parody needs to mimic an original to make its point, and so has some claim to use the creation of its victim’s imagination, whereas satire can stand on its own feet and so requires justification for the very act of borrowing.” Parody, according to the court, meant, “Second work by a different author that imitates the characteristic style of the first author … to ridicule or criticize the copied work.” However, satire meant a work in which “prevalent follies are assailed with ridicule or attacked with irony, derision or wit.” The Supreme Court of the United States, in this case, made it clear that while parody was entitled to the defense of fair use, satire was not.

On the other hand, in May this year, the Delhi High Court had an interesting case before it. Netflix aired a web series on its platform named “Hasmukh” which is a dark comedy about a small-town boy who arrives at Mumbai to pursue his career in stand-up comedy. Something weird about Hasmukh, the protagonist, is that he can only successfully perform his act if he commits murders before his performances and makes jokes about his victims. During one of the episodes, Hasmukh has been shown to have had an upsetting experience with a lawyer. The lawyer is someone dishonest and greedy. During the same episode, the protagonist allegedly makes derogatory remarks against the entire legal fraternity. So, a suit was filed before the Delhi High Court seeking a stay against further airing the web series. The court in Ashutosh Dubey v. Netflix (2020) sat to decide whether the above situation amounted to freedom of speech and expression under Article 19(1) (a) of the Constitution of India. Although the case was decided based on the above contention, the court made certain remarks on what a satire is. The court said, “Satire is a work of art. It is a literary work that ridicules its subjects through the use of techniques like exaggeration. It is a witty, ironic, and often exaggerated portrayal of a subject.”

Another instance when the court considered the issue of satire was in the case of Indibily Creative Pvt. Ltd. vs. Govt. of West Bengal (2019). It was the Supreme Court that held that “A Satire is a literary genre where issues are held up to scorn by means of ridicule or irony. It is one of the most effective art forms.” The difference between Parody and satire has not been accepted or developed by the Indian courts in the context of IP Laws. This means that whether a work is a parody or a satire, the defense of fair use can be claimed by the defendants and the work shall also be entitled to claim separate copyright protection as well. This is because the courts in India have considered both these forms of expression as a work of art and have characterized them under artistic expression.

Parody and Fair Use

Parody is included under a category of works allowed under Section 52(1)(a)(ii) of the Copyright Act, 1957. This provision provides for ‘criticism or review, whether of that work or any other work.’ Parodies usually are essentially a criticism of original work and are therefore included in the list of works allowed in the above provision. However, it isn’t as simple as it sounds. The real problem starts when you have to prove that your work was a parody and not an infringement on the rights of the original copyright holder.

To prove that your work is covered under parody, you have to satisfy two conditions which will essentially conclude as to whether it is covered under fair use or not. They are, Firstly, you must not have intended to compete with the copyright holder. This is also called the Market Substitution Test and Secondly, you must not have made ‘improper’ use of the original work. These conditions were laid down in the case of Blackwood and Sons Ltd. & Ors. v. A.N. Parasuraman & Ors. (1959)

So, if you can prove that your work has not impacted the potential market of the original work and that the parody and the original work cater to two completely different sets of audiences, you would have passed the market substitution test. This is tricky because applying this rule strictly is impossible for the simple reason that one is not quite sure if the categorization of the audience can be done in the manner that this rule presupposes. If the court looks into the commercial gains made by the parody to see if the parodist has competed with the original author, then that too wouldn’t be an effective mechanism. Kris Ericson writes, that, even if the parody has made commercial gains by criticizing the original work it doesn’t mean that it has made inroads into its potential market. Infact, he goes on to mention that, it has indirectly helped the original copyright owner by publicizing the original work and for lesser-known works, it has served to make it more famous/popular.

The Transformative Work Test

To meet the difficulties that could arise while analyzing the first condition, the courts have evolved the “Transformative Work” Test. This test was also used in the Campbell case where the US Supreme Court held that the relevant question to decide in such circumstances is to see “to what extent the new work is transformative, i.e., to what extent the new work alters the original with new expression, meaning or message.” This test has therefore substantially downplayed the commercial use argument and if the parodist can show that his work is transformative, he would be entitled to fair use defense. However, what qualifies as a “transformation” under this test has to be decided by the court on a case-to-case basis.

In Leibovitz v. Paramount Pictures Corporation (1998), the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit was faced with a dilemma. Leibovitz is a well-known photographer. Among her most famous works is the photograph of the actress Demi Moore. Moore was pregnant when the photo had been shot by Leibovitz. She was depicted nude with a serious facial expression. The photo was shot keeping in mind various aspects such as skin tone, body positioning, and lightning, among other things. The photograph gained popularity in very little time. Paramount pictures, sometime later, published a photograph of the actor Leslie Nielsen where the company had used the same concept behind Leibovitz’s photo. The company used the photo of a naked pregnant woman, which was shot using similar lightning, body positioning, etc. and superimposed the ‘smirking’ face of Nielsen in the place of the woman. Now, the question that the court had to decide upon was, whether this amounted to a transformative work at all. The court held that Paramount’s use was transformative because it had imitated the original work and had brought in a ‘comic effect or ridicule’ which was an addition to the original work. The court also held that Nielsen’s photo with a smirking face had a contrasting dissimilarity with the serious expression of Moore which may be perceived as commenting on the ‘pretentiousness’ of the original.

In R.G. Anand v. M/s Deluxe Films (1978), the Supreme Court in India has held that “Where the theme is the same but is presented and treated differently so that the subsequent work becomes a completely new work, no question of violation of copyright arises.”

However, a work does not become a parody simply because there is humor inside it. If it is found that the parodist has tried to use a famous work to gain more commercial benefit by simply incorporating humor in the work, it wouldn’t be considered a parody. For instance, during the fag end of 2015, a US court was hearing an exciting case. The defendant, who was an apparel company, had used the iconic Superman logo on its T-shirt. The T-Shirts featured the word “Dad” in a superman-styled logo. They claimed that SuperDad T-Shirts by the defendant were an obvious parody of the Superman logo and therefore there is no likelihood of confusion that could be caused to the consumers. They infact claimed that the word ‘Dad’ was used to point out Superman’s ‘undue self-importance’. The court was sitting to decide on the motion to dismiss the complaint. The judge disagreed with the arguments of the defendant and held that although the defendant’s use of the word Dad is humorous, it is only to promote the t-shirts using the logo of the plaintiff, and therefore it is not a parody.

What does the SupermanSuperDad fiasco show? It shows two things in particular. It shows how a defense of parody will only succeed if the work is not likely to confuse the consumers as to the source of the work. Secondly, it shows how parody has to be more than being just funny especially when the work is purely commercial in nature. It has to make some commentary on another’s work. The commentary must be meaningful and must not be simply to utilize someone else’s work to increase your sales.

Parody and Moral Rights

Moral Rights are inalienable rights granted to an author of a copyrighted work. They exist independently of Copyright. The author of an original copyrighted work, even after agreeing to alienate his exclusive economic rights, retains moral rights in his works which can be enforced when the need be. They give the right to the author to have the work attributed to him which is also known as the right to paternity.

Moral Rights were included in Article 6bis of the Berne Convention way back in 1928. Section 57 of the Copyrights Act, 1957 grants protection against any act of distortion, mutilation, modification, or any other untoward act done to an author’s original work in which copyright exists. Acts which prejudice the honor or reputation of the creator of the work is read as a violation of the Right to Integrity, which also forms a part of Section 57.

It is to be understood that parody directly infringes upon the moral rights of the author of an original work. This is because it is based on ridiculing and mocking the copyrighted work. This is where the second test to claim parody as fair use comes in. We do know that to claim fair use defense in parody, the parodist will have to prove that he did not use the original work in an ‘improper’ manner. But the test becomes difficult to theorize because of a lack of a clear definition of the word ‘improper’ and as to what it entails.

Here, there are issues relating to freedom of speech and expression (argued by the parodist) as well as those related to defamation law and claim over one’s right to dignity (argued by the author of a copyrighted work). It is to be understood that freedom of speech and expression is not an unbridled right. It is infact a right with reasonable restrictions. This means that a parodist is not allowed to ridicule or attack the work such that it can be imputed to the author of the work.

How can this distinction be made is a question of fact which the courts have to decide on a case-to-case basis. Usually, the courts apply what is called “The line of Creativity” principle. This principle draws a line between the parodist’s creative application of ideas and expressions to criticize the original work, and, the insult or humiliation intended towards the author of the original work. Such an inquiry is for the courts to do. But while doing such an inquiry the courts need to draw a distinction between innocent humor and defamation intended against the moral rights of an author.

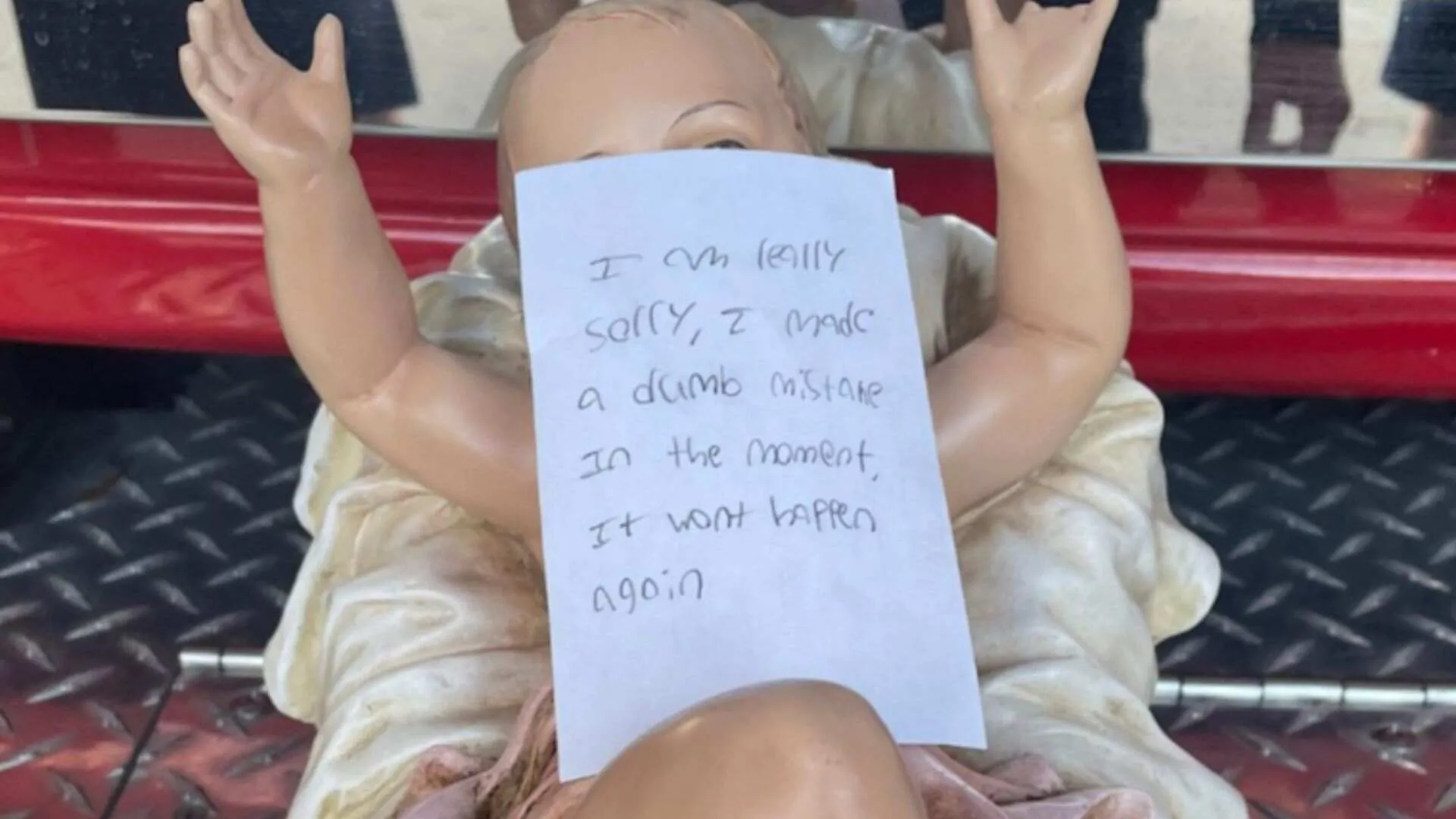

Notably, the Australian Supreme Court laid down the ‘bane and antidote Test’ in the case of Charleston & Smith vs. Newsgroup Newspaper Ltd (1995). The test laid down a rule that if any defamatory text or picture is accompanied by a disclaimer prescribing that the work has been used just for humor purposes then it must be taken only for humor purposes and nothing more or nothing else. This was a big development.

The growth of new media technologies has increased the number of actors, standup comedians, bloggers, and other stakeholders in copyright law. The use of original copyrighted works, without the permission of the author of the work, has almost become a norm and a social and cultural behavior. This is all being done in the name of a joke or a parody. Majority of these contents violate the moral rights of authors of original works and are offensive. The rest use parody as a fair use defense for works that are purely aimed at commercial gain. Such infringements need to be regulated in an age of digital India to grant incentives for creators to create more works of artistic expression. The different tests adopted by the courts have to be applied equitably. In the longer run, this will further the goal of Intellectual Property to balance the rights of the Authors as well as those forming part of the citizenry.

Anurag is a student of National Law University, Visakhapatnam and can be contacted at anuragtiwary66@gmail.com Abhinav is a student of law from Amity University, Noida and can be contacted at narayanabhinav14@gmail.com