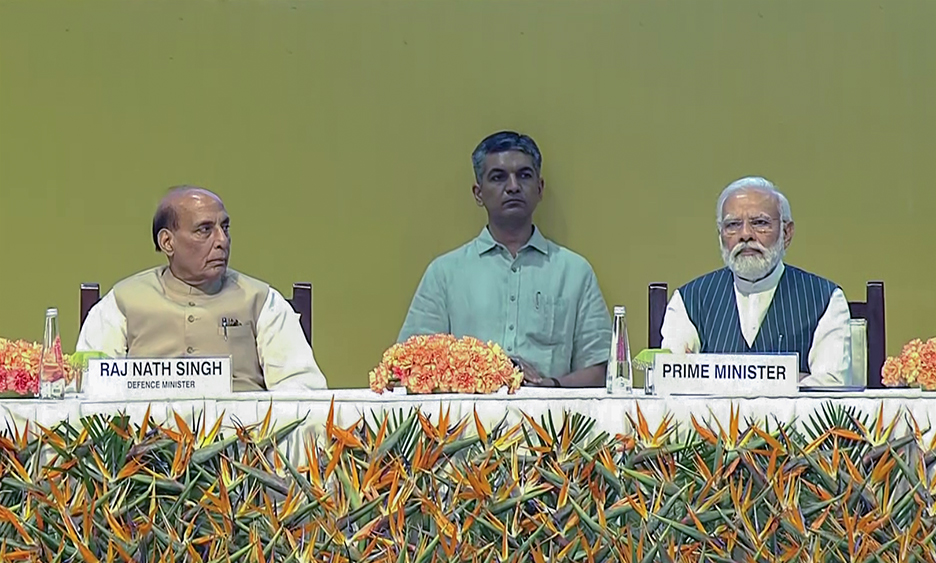

The Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), India’s premier R&D organization working on various areas of military technology to qualitatively address the needs of the Indian defense ecosystem, is up for a massive overhaul under the visionary leadership of the Prime Minister Narendra Modi-led government.

A nine-member committee comprising retired and current military top brass, ISRO scientists and industry experts, headed by former Principal Scientific Advisor to Government of India, Prof K. Vijay Raghavan, has been appointed with the task to revamp the DRDO. The Union government has made a crucial step in its quest for space-age technology for future wars by forming a high-powered committee. The major objective of the committee is to redefine the mandate and purview of India’s top defence research organization, the DRDO. With a budget of Rs 23,264 crore for the fiscal year 2023–2024, the DRDO has frequently come under fire for project delays and budget overruns. The nine-member group, chaired by former chief scientific adviser Professor K. Vijaya Raghavan, is anticipated to present its report within three months with the goal of addressing these issues and reviving the DRDO.

Lethargic defence PSUs (DPSUs), which are more like white elephants, lack of innovation, and an absence of institutional drive in the manufacturing of weaponry for the armed services, India faces enormous obstacles in becoming a net exporter of arms.

Under age old socialistic model of governance, the nation has failed to create a competitive domestic defence industry, despite significant expenditures in DPSUs. India barely invests $62 billion on defence R&D, compared to China’s $372 billion. This is a huge gap that needs to be reduced. For this, the DPSUs need to be revitalized by gradually privatizing huge, inefficient ordnance units and allocating the funds freed up to R&D.

The United States’ Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) model is being examined as a way to foster domestic innovation. The development of cutting-edge technology for the American military is the responsibility of DARPA. It partially does this through providing money for research initiatives in businesses of different kinds, from small startups to major multinationals. The Internet itself is its most notable technological accomplishment. This appears to be consistent with the Kelkar Committee’s advice to pursue parallel development using a DARPA-like paradigm to supplement DRDO efforts.

The US defence development organization DARPA, which has an annual budget of roughly $3 billion and is credited with inventions like the Internet, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), stealth aircraft, etc., only employs about 300 project managers, who deliver results in collaborations with private sectors. In comparison, the DRDO has an annual budget of $2 billion, has approximately 60,000 employees, half of them constitute unproductive administrative cadre and officials on deputation from MoD. The renowned CMMI accreditation from the US Department of Defence (DoD) and DARPA is what determines how mature systems engineering capability is. India now has a large number of CMMI Level 5 enterprises, giving it the technical base it needs to take on pertinent system engineering projects and provide defensive systems and goods.

The committee’s objectives cover a variety of important aspects. It will make recommendations on how to increase the engagement of startups and academics in the creation of cutting-edge technology. They will simultaneously examine how the Department of Defense’s (R&D) and DRDOs’ duties should be reorganised and redefined, as well as how they should interact with academia and business.

A strategic shift in the DRDO’s focus is at the heart of this revamp. Instead of meeting the immediate needs of the armed forces and indigenizing existing systems, the DRDO plans to focus its efforts on pioneering high-end futuristic technologies in air, ground, maritime, and space systems. This realignment is expected to result in the elimination of certain ongoing tasks that could be better managed by academia or industry.

Historically, India’s defence manufacturing achievements have frequently revolved around the production of obsolete weaponry, the establishment of manufacturing units for foreign weapons, post-technology transfer, or the replication of foreign platforms with minor modifications. DRDO, on the other hand, has demonstrated excellence in missile and radar technologies. The government intends to transform DRDO into a force similar to the DARPA model used by the United States. The DARPA, founded in the same year as the DRDO (1958), adheres to the philosophy of being a proactive initiator rather than a passive victim of technical shocks. DARPA, unlike DRDO, is a financing organization with no laboratories or research personnel. Contracts with universities, corporations, and government R&D organizations are used to perform research.

This revision is consistent with the Indian government’s goal on strengthening domestic defence industry through initiatives such as Atmanirbhar Bharat and increasing defence exports. The strategic partnership concept invites private companies, start-ups, and universities to work with the DRDO and other organizations to design and build military platforms and equipment.

With this transition, India’s defence R&D sector hopes to vault into the realm of cutting-edge technology. The reformed DRDO, with a more focused mission and more participation from academics and private business, shall pave the path for India to emerge as a powerful global leader in military technology and innovation.

Siddhartha Dave is an alumnus of the United Nations University in Tokyo and a former Lok Sabha Research Fellow. He writes on foreign affairs and national security.