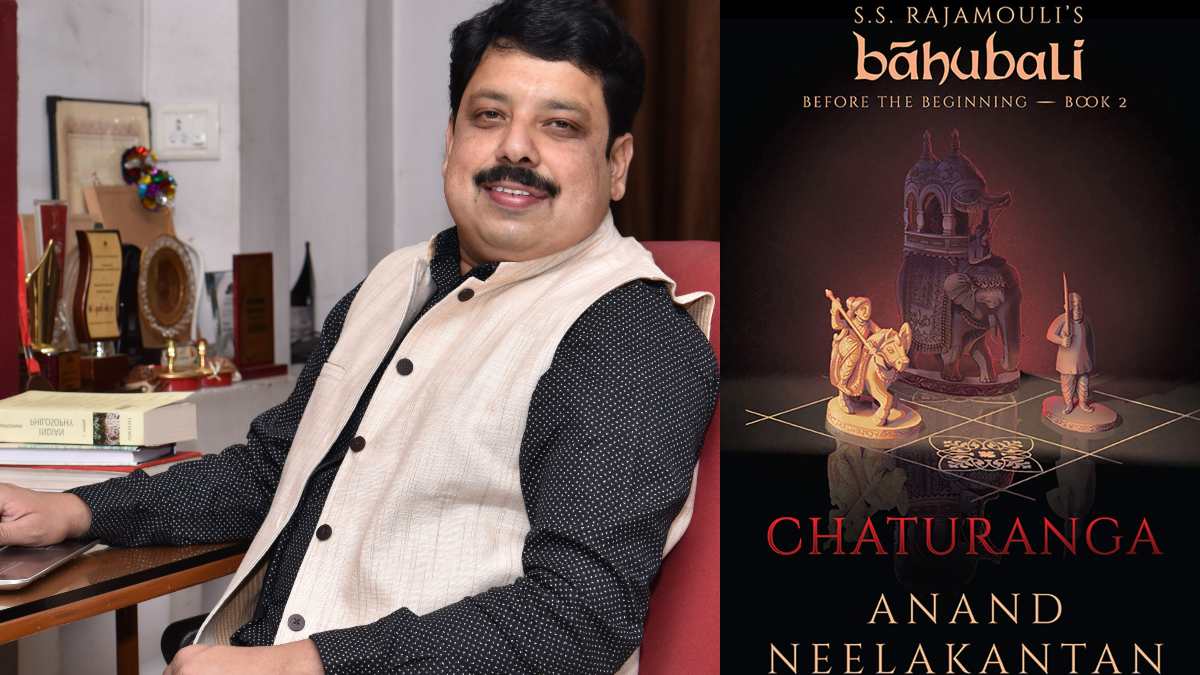

Known for his keen retelling — or counter-telling — of episodes from Indian mythology, Anand Neelakantan is now working on a trilogy based on the blockbuster Bahubali films. The acclaimed author spoke to The Daily Guardian about Chaturanga, the second book in the series which has just come out, and how writing within certain narrative boundaries is just like cultivating a garden.

Excerpts from the interview:

Q. Chaturanga tells a tale about the nexus of power, gender and caste, and the strategy needed to navigate a hierarchical and unjust society. Did you draw any inspiration from contemporary politics and social issues while writing the book?

A. All my books draw from contemporary politics and social issues. The story may be set in Lanka, Hastinapura, Kishkinda or Mahishmathi of many thousand years ago, but the issues the characters face would be those of now. If you read between the lines, you can perhaps get which events in recent history or which political character I am alluding to in my books. I believe human nature and human experience remain unchanged across time, culture and location.

Q. Sivagami is a rather grey character and her quest for vengeance culminates in a bloody act of violence at the end of this book. Tell us about how you carved such a complex character.

A. The story deals with medieval politics. Violence is a close cousin of power and deceit is the sibling. For a book series spanning three books, a simplistic story of good triumph- ing over evil would not work. A book does not have the advantage of visual storytelling where a simple story can be told spectacularly with the help of visual effects, stunts, scale of production and music. A writer has to depend on intriguing plots and deep characterisation to tell a gripping story. I had no choice other than to make Sivagami complex. The advantage of that is that it would make her more relatable and humane. The disadvantage is disappointing those who relish perfect squeaky white heroes and coal black villains.

Q. What sort of research did you do while shaping the fictional Mahishmathi and its people?

A. I had set up the timeline as sometime around 8th century in the Deccan for my Mahishmathi. I had taken the clue from the scene in the film where a Middle-Eastern merchant comes to sell a sword to Kattappa. My research involved knowing more about this historic period, the way people dressed, the social structure, etc. Though strictly not from this period, I have drawn a lot from the Vijayanagara Empire, the Kakatiyas, Cholas and Cheras for modelling different kingdoms. The species of horses that were imported, the folk songs of this period — all these little details I have carved may perhaps delight a reader who is aware of these things. For the majority of readers who may not care about it, I have tried to make the novel as thrilling as possible and I can only wish they would come back to read the book at a slower pace later.

Q. Even though you are authoring the books, their narrative has to adhere to the Bahubali universe which began with the films. Does that pose any sort of limits on your writing?

A. Any creative art needs boundaries and limitations. Art and literature have rules and I accepted that I have to adhere to the Bahubali universe while crafting this novel series. It is like a gardener being handed over a patch of land. There are boundaries, there are some rules on what he could cultivate, the seed he is given, the nature of soil and availability of water. Yet, the gardener must create a beautiful garden. If there were no limitations or boundaries, there would be no garden but a patch of wilderness. My job was that of a gardener.

Q. With a massive set of characters and multiple themes, this is a trilogy of epic proportions. How do you keep the threads of the plot together while writing?

A. I go with the characters. I am an organic writer. I sow the character seeds and water them with my imagination. I let the characters grow, pruning them here and there, allowing some to grow bigger, some to remain in bonsai form and so on. If I was approaching the story writing as how an engineer makes a building, then I would be worried about the plan and about keeping a strict adherence to the plan. Here, I consider myself as a gardener and let the plot grow by itself. I need to keep checking the blueprint.

Q. You have written novels, scripts for TV, and now this trilogy of novels based on films, which is about to get adapted for Netflix! How did you adjust your writing process to each situation?

A. Each is a different art. I am experimenting with different writing forms. I write columns in newspapers. I have written more than 500 hours of scripts for TV, published poetry, short stories, finished a script for a feature film and have now ventured into children’s books. It is like a cricketer playing T20, one-day matches and Tests. Each may require a different temperament and skills, but all of them are cricket. The basic rules remain the same.

Q. As an eminent author of the genre, what would be your advice for aspiring writers of mythological fiction?

A. I don’t know whether I can advise anyone. What I would suggest to any aspiring writer of any sort of fiction is to be prepared for a lot of rejection and criticism. For fiction derived from our Puranas, please do not restrict your research to Google. Most of the Puranic stories are still in an oral format and there are hundreds of variations of the same story across Asia. Never approach them in a dogmatic fashion and never write stories derived from Puranas unless you are passionate about them. It is back-breaking hard work.