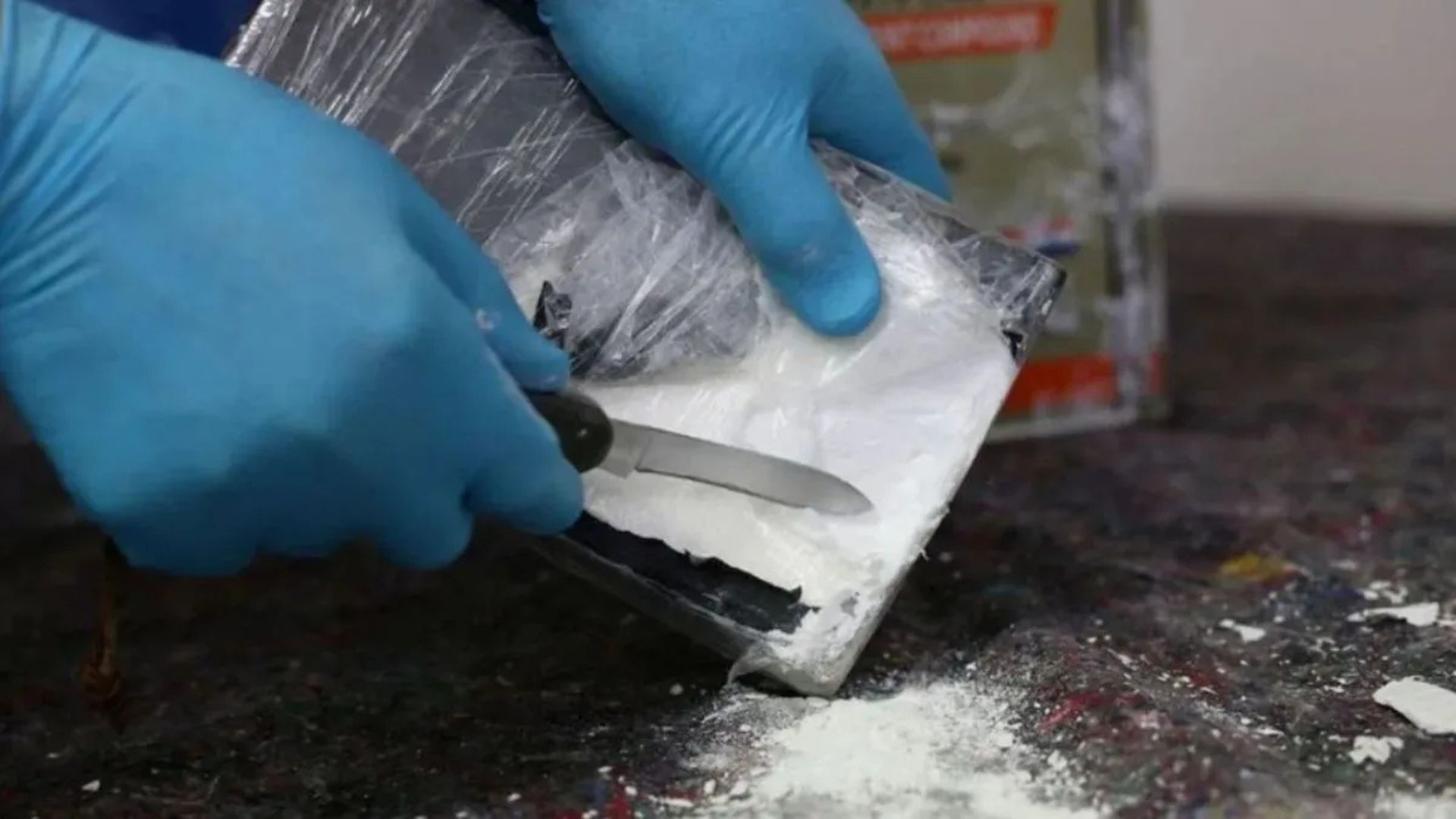

It was exactly 42 years ago on 25 January 1981 when the Police Control Room received a call from the residence of a Union Minister on Ashoka Road that Constable Tejpal Singh posted there as a security guard had been shot dead by an intruder. Being the eve of the Republic Day. Senior officials rushed to the spot but subsequently got busy with the parade arrangements. A small item appeared in the newspapers on 27 January which recorded the death of the Constable. The matter would have been buried but an old friend working in the police tipped me off and asked me to go deep into the incident. I was covering Crime for the Patriot in those days and as per the information relayed to me, there was no trace of blood found on the scene of the crime. This was very unusual since Tejpal had been report-

edly shot by the alleged intruder from point blank range and there had to be blood on the floor

and other places. I was completely intrigued and decided to do some home-work before following the case. I took out Modi’s jurisprudence from the book shelf in our house; my parents were both doctors and thus this book was in their collection. Modi in forensic circles was regarded as the last word on medical jurisprudence. I went through various chapters and during my search came across reference to two kinds of wounds—ante mortem and post mortem. Both the types

had been explained very well. Next morning, I called on a very senior officer associated with the

case and asked him to confirm whether there had been any blood marks at the scene of the crime. He looked at me in bewilderment and seeing Modi’s jurisprudence in my hand, confirmed that no blood had been found. That evening I filed a story for the paper where I raised the question whether Tejpal was already dead when he was shot and that is why there was no blood found. His gun shot injury was post mortem, implying that he was already dead when he was shot and the intruder theory and his identity kit portrait released to the media were attempts to cover up the truth. There was furore in the Police circles. Later I was able to access the autopsy report which stated that Tejpal had been shot in the chest and the bullet had pierced his heart, lungs and liver. How would that be possible if he was shot from point blank range and unless the bullet was fired when he was lying on his back by a person who sat next to his body to pull the trigger. Not satisfied with police explanation, I went to the office of Dr Bishnu Kumar, Head of the Forensic Science department at the Maulana Azad Medical College. Dr Kumar was not there but a colleague of his endorsed my hypothesis of Tejpal being dead when shot. In response to my query that was there any way a person could have been killed without it showing in the post mortem? The doctor said that an over-dose of a certain drug could kill a person and the trace of it may not be found even in viscera. After a few stories revealed the mysterious aspects of the case, I was called by my Editor and asked not to pursue it any further. A senior minister had vis-ited him that morning and had requested him to stop the reportage. This was amongst many cases I covered while covering crime or supervising the aoverage in my other papers as well which included Times of India, The Hindu and The HindustanTimes. This was a murder most foul and on the last day of his tenure, the then Police Commissioner Pritam Singh Bhindar presented a sewing machine to Tejpal’s widow. This was sometime inDecember, 1981. The point is that there are multiple cases which never reached the conclusion because of interference from the top and this was

one such matter.