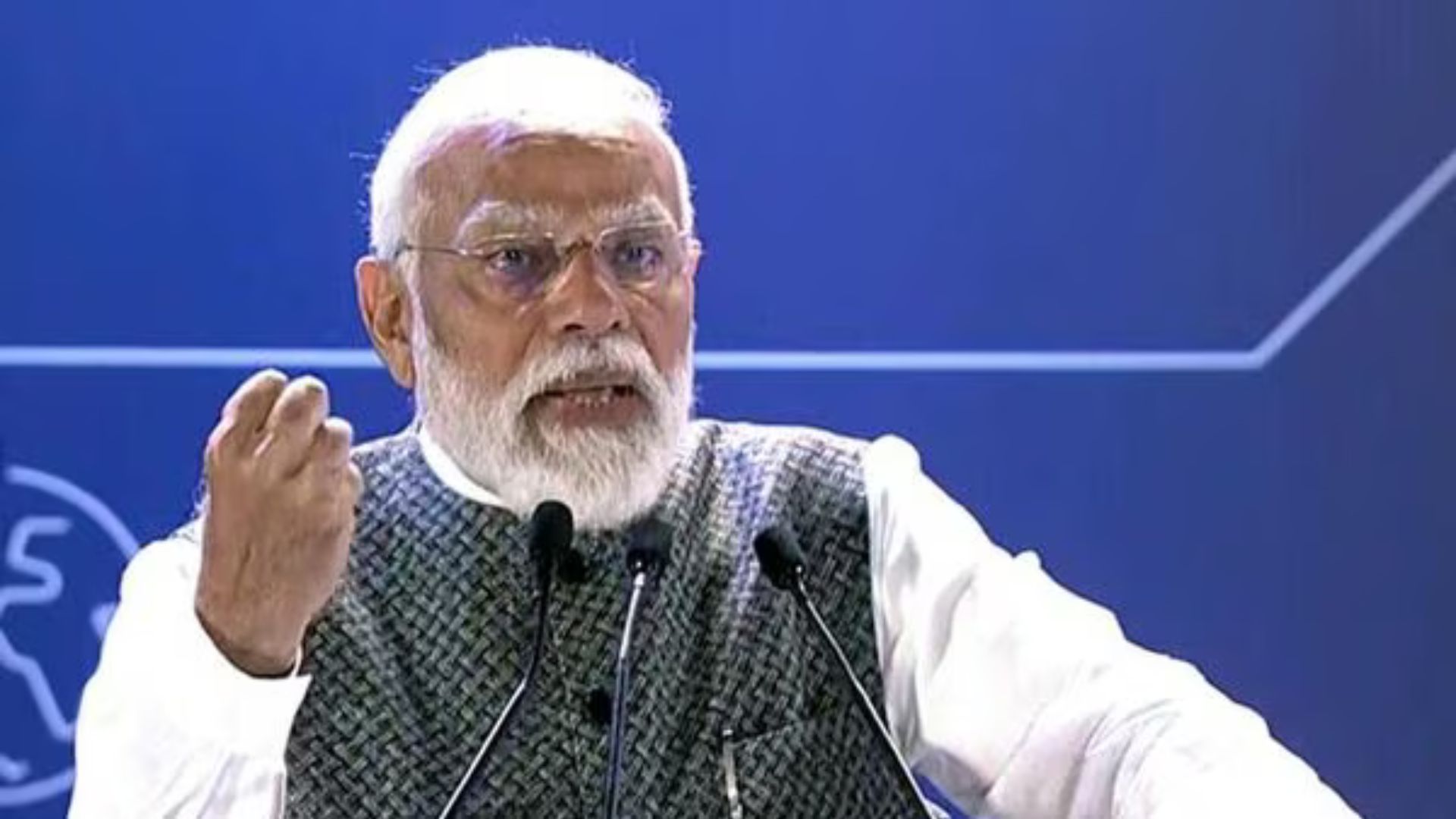

Less than a week ahead of the beginning of the Lok Sabha elections of 2024 on 19 April, the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party came out with its electoral manifesto, or sankalp patra, called “Modi ki Guarantee 2024”—thus making the elections all about the personal guarantees being given to Indians by Prime Minister Narendra Modi. And why not? In both 2014 and 2019, specifically in 2019, the elections were all about voting for Narendra Modi, with the message that every vote cast would go to him, which worked wonders for the BJP.

In 2024, in the PM’s own words, the BJP is looking to better its earlier tallies. Whether the BJP-led NDA can truly go “400-paar” or not will be known on 4 June, but indications are that “Modi ki guarantee” is likely to propel the alliance towards a comfortable majority. For a long time, manifestos were regarded as documents where political parties made promises that were too tall to be kept. But not so with the BJP under the leadership of Narendra Modi. BJP’s promise in its earlier manifestos of abrogating Article 370 or building the Ram temple had never been taken seriously as they were deemed as tasks next to impossible.

But PM Modi ensured both were made possible inside his first two terms. With two of the BJP’s three core promises fulfilled, it’s but natural that the party will now focus on its third promise, a uniform civil code. The other promise that will be keenly watched is “one nation one election”.

Without doubt, these two are the most contentious of all the guarantees given in the manifesto and may prove hard to implement. If implementing the UCC by the Uttarakhand government is taken as a test case, it has been a mixed bag and has thrown up certain issues—such as criminalising the failure to register live-in relationships—that need to be resolved before the UCC bill is tabled in Parliament. Also, Uttarakhand is a tiny state.

Implementing the UCC all over the country will need to take care of far greater complexities. According to media reports, the UCC bill could not be tabled in the 17th Lok Sabha primarily because the 22nd Law Commission, which is drafting the bill, is yet to finish the consultations with different stakeholders.

In this context, the most difficult will be codifying the personal laws of a particular minority group. While the biggest hurdle will be the spreading of misinformation and disinformation, urging the Muslim community in particular to take to the streets in protest, just the way it happened in 2019-2020 with Citizenship Amendment Act. And CAA has nothing to do with the Indian Muslim community, while the UCC affects them directly. The UCC is already being projected by certain vested interests as a means to oppress India’s minorities—an untruth that must be busted. Politics has already started on the UCC, with leaders like Mamata Banerjee promising to uphold the Muslim man’s right to have four wives simultaneously. To counter all this, the message has to go out that the UCC is needed for the protection of Muslim women. The same people who follow a uniform code in the western countries, are protesting against its implementation in India. While the experts and stakeholders iron out the creases in the UCC draft, the messaging has to be mastered. The BJP needs to realise that messaging is a problem with its government, as we have seen in the cases of both Article 370 and CAA. India can do without another street unrest that drags on for months, leading to a loss of productivity, deterring progress and destabilizing the country in general.

As for the promise of One Nation One Election, to hold all Assembly elections along with the Lok Sabha elections is a complex affair, even if logistically possible since the Election Commission is already adept at conducting a nationwide general election as well as some state polls simultaneously. The problem will be political. Will an Opposition party, if it has come to power in a state a year or two ahead of the general elections, be ready to sacrifice its government ahead of time for the sake of “one nation one election”? Or what if a particular state throws up a hung Assembly in the election? Implementing “one nation one election” will not be possible without having all the opposition parties on board, and the way things are between the government and the opposition currently, that’s a very tall ask.

So it will be interesting to see how the government, if it returns to power, navigates this rocky road.

On the whole, the manifesto is strongly focused on governance and promises to take the policies that have been implemented by the Modi government, a notch or several notches higher, while exploring several new areas that can lead to economic prosperity for the country. It does not make any shrill promises of freebies or doles, except for continuing with what is already being given by the government to certain segments. Given that the principal opposition party, the Congress is promising doles that may prove to be popular but can be fiscally ruinous, for the BJP not to pursue a similar path ahead, is a mark of confidence. But then Prime Minister Modi is focused on governance, so his guarantees are all about what can be delivered and some more.