On March 27, 2020, the Indian Government gazetted the 2020 Finance Act, which inter alia expands the equalization levy (first imposed in 2016) to cover all kinds of digital e-commerce transactions into India, as well as those transactions which use Indian data. The new 2% levy will apply on consideration received or receivable by non-resident e-commerce operations from e-commerce supplies or services facilitated on or after April 1, 2020.

The rationale behind the government’s decision to tax the digital economy is not hard to understand. The principles of international tax law followed today were written several decades ago and have outlived their utility in today’s digitalized era. For instance, under tax treaties, a source country cannot tax business profits of a non-resident company unless that company carries on business activities in the source country through what is called a “permanent establishment”.

For a permanent establishment to exist, a company must have either a physical presence (mainly through setting up of offices) or a representative presence (through agents or employees) in the source country. Highly digitalized businesses that rely on hard-to-value intangible assets, data and automation can obviate such a presence, thereby escaping the corporate income tax net in the country in which they derive revenue from.

Such is the significance of the issue that the OECD, which explored ways to address these challenges as part of its ambitious base erosion and profit shifting project, failed to inspire international consensus on how the nitty-gritty of how such an international tax system could be designed. While the OECD is currently devising long-term solutions and is expected to deliver a final report by 2021, its slow progress prompted many countries to take short-term, unilateral measures to address the problem.

But the government’s decision to tax big US digital companies is likely to alarm the US government. Seven out of world’s ten largest online companies are based out of the US. The profits of these businesses were primarily taxed, if at all, in the US. However, changes to international tax rules pertaining to allocation of taxing rights between source and resident countries would mean that the US would get to enjoy a much smaller part of the tax pie.

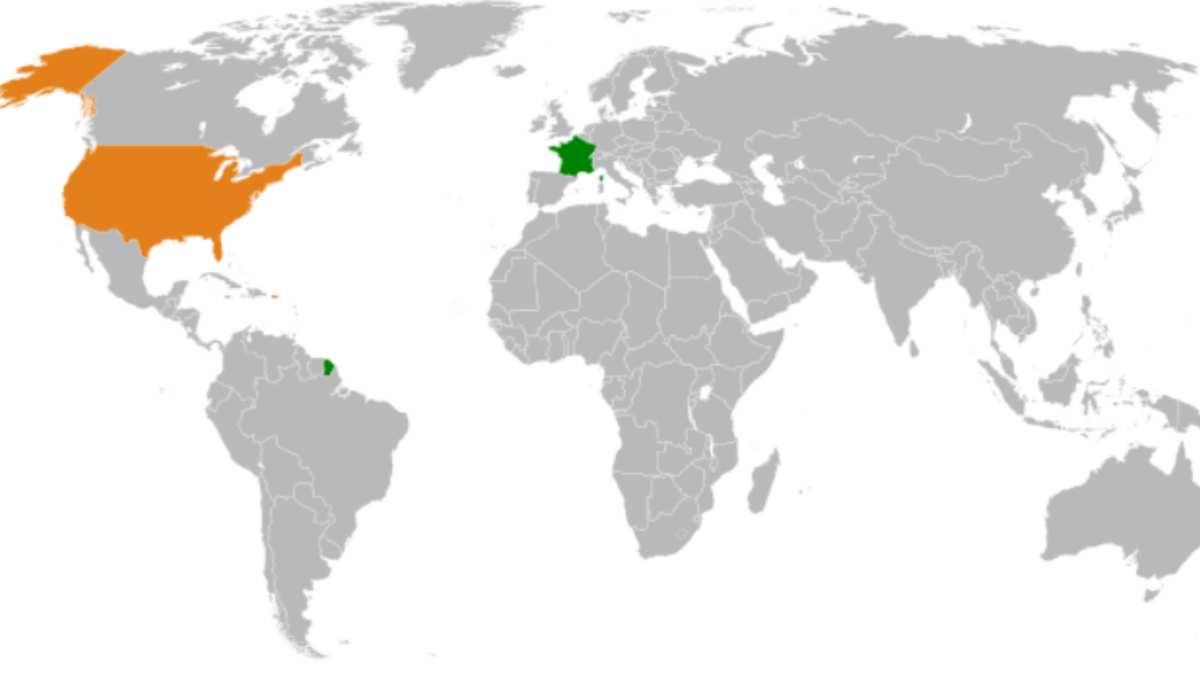

Take the example of France. When France imposed its 3% digital services tax on large US digitalized businesses (with annual global revenue of over USD 800 million) such as Google, Amazon, Facebook and Apple (termed in France as “Les GAFA”), the US trade representative responded by imposing additional duties of up to 100 percent tariffs on French products worth USD 2.4 billion.

According to the US trade representative, the French digital service tax unfairly targeted large Silicon Valleybased digital businesses, is discriminatory in nature, and harmed the US’ interests. Soon after US’ decision to open an investigation was revealed, French President, Emmanuel Macron, struck a deal with the US government according to which it promised to abolish the tax and reimburse the tax paid by US businesses as soon as an international agreement on digital economy taxation is reached.

Digital economy taxation has not troubled Europe alone. In fact, the worst affected are developing countries, such as India, which provide a huge consumer market for foreign digital brands. For instance, Amazon has a market share of over 30% in India, while Google and Facebook together claim 68% of India’s digital market. Additionally, India’s internet users are expected to reach 627 million this year. These numbers are bound to increase over time in the coming years as the Narendra Modi-government vigorously campaigns for a “Digital” and “Smart” India

While the profits that US digital businesses make out of their Indian operations increase every year, there is only a small of percentage of corporate income tax that the Indian government is able to collect from them. Companies such as Google and Facebook reportedly made INR 100 billion in revenues from the Indian market, but only paid INR 2 billion in taxes. Therefore, it goes without saying that international tax rules must be revisited.

The question, however, remains if India can afford to change tax rules unilaterally and risk foreign investments. Last time, when India sought to impose rules requiring US companies to store data in India, US President Donald Trump retaliated with a cap on H1B Visa. Trump has also been a vocal critic of India’s “unacceptable” import duties on certain US products. This is bound to be repeated if India sticks firm on unilateral digital economy taxation. India needs to learn a lesson or two from the French experience and wait for more concrete measures from the OECD before taking unilateral measures.

Ashish Goel is an international tax lawyer with COMTAX AB. He practices at the Supreme Court.