Lapsing onto the tables since 1996, patriarchy wrenched the pages of women’s reservation; thence, the ensconced ‘political equality’ remains unlearnt.

Amidst the debate of gender inequality or equality, the notion of women’s rights, the feminists’ theories actualize; considering, if the male to female ratio can ensure equality if the Constitution of India under Article 14 envisages gender equality and equity in the country, so why the electoral representation of women in the parliament in still under scrutiny. With the changing dynamics in the country, women are given more rights as compared to the older times, but the rights concerning the reservation in parliament in still pending to be marked in the checklist i.e. the enactment of the Women Reservation Bill or the Constitution (108th Amendment Bill) 2008 by the Parliament of India. The script of the Constitution in defining equality has not been truly implemented in terms of “political equality” why, because, women are still considered weak and unqualified and are still expected to settle down and look after the kids. The women namely, Mrs. Pratibha Patil, Mrs. Sushma Swaraj, Ms. Jayalalitha, Mrs. Nirmala Sitharaman in Indian politics had pasted a huge impact on the minds of Indian Citizens and have proved to be worthy in governing the nations constituency has been negated by the houses of the parliament because, when we go on to talk about Women in Indian Politics, we hear very few names of female politicians because women are not ascertained with neither the equal representation nor with the equity representation in the parliament; Should we consider “patriarchy” or “ruling by men” is a tendency in the country?. As women are taught to be under the tree of the men who take major decisions in almost every sphere of life and society and are encouraged to voice their opinions. The female representation in Indian politics has come quite far over the years but has a very long way to go. One major way to facilitate the increase in representation is through the recognition of the women already present and encouraging more women to get into politics and give them the right opportunity to hold positions of power and have a strong say in the decision-making process.

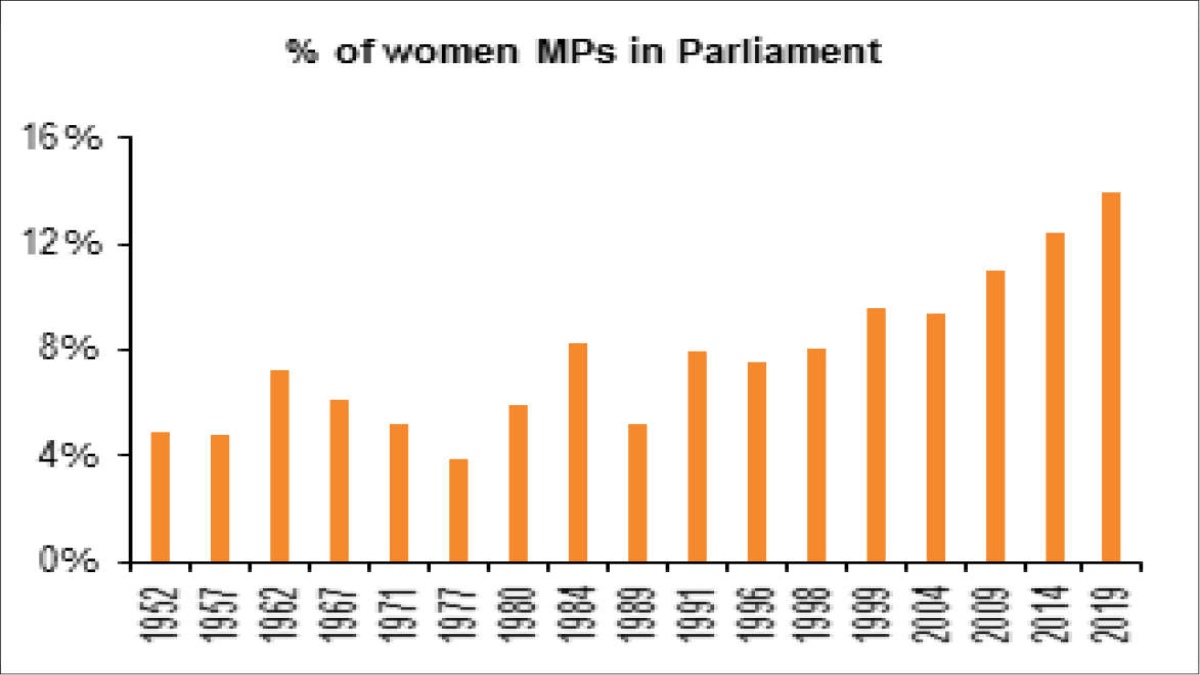

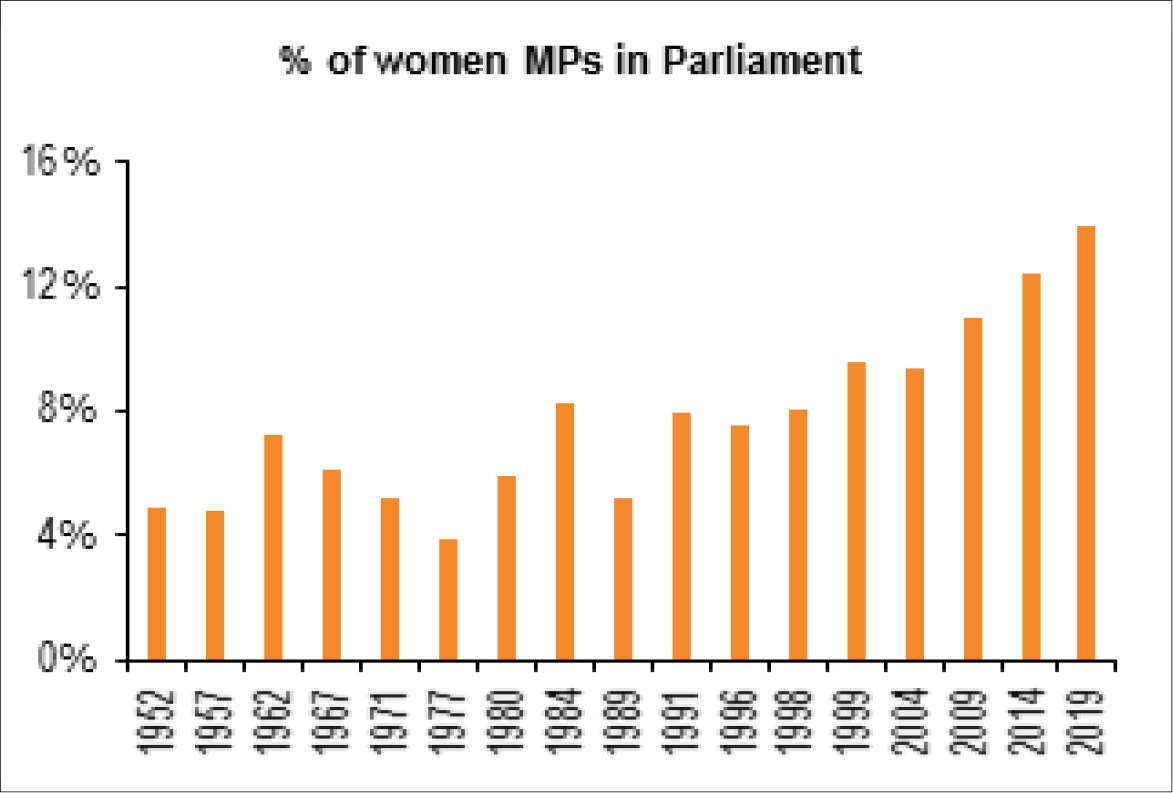

Fig. 1: Representation of Women in Rajya Sabha.

Fig. 1: Representation of Women in Rajya Sabha.

WOMEN’S REPRESENTATION IN INDIAN PARLIAMENT

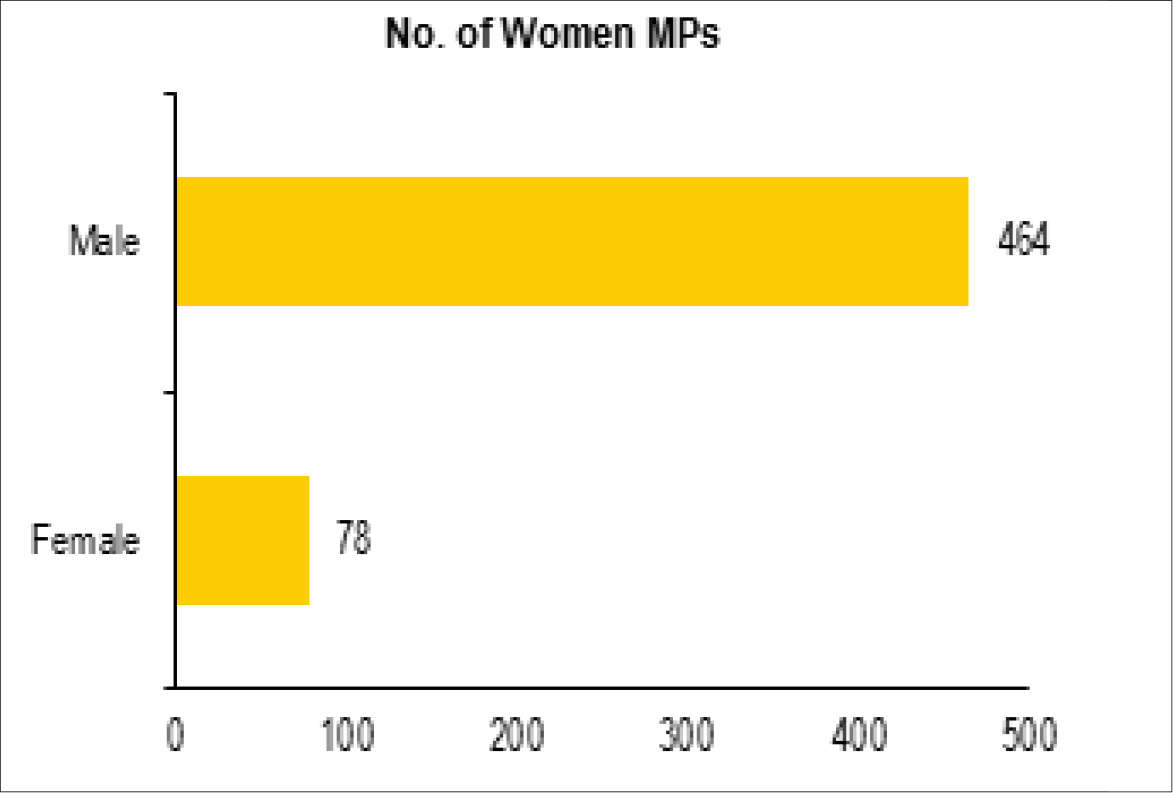

The real decision-making process involves a maximum number of male parliamentarians even though the country experiences a minimal increase in every election in the representation of women candidates in politics. Although the majority of the political parties blossoms the papers by including women in the parliament by icing it with the term called “reservation to women”, but the actuality is hidden in regards to equal electoral representation to women in India. The dearth of women’s representation in the parliament has succinctly depleted the value of the nation’s glory which was also highlighted by India’s first woman President, Pratibha Patil, as she said, “There is simply no way our nation can progress if its women population is left behind.” But, this dearth is escaped through a fallacy called “lack of winning capacity of women”. The persuasion of this fallacy was been bereft in the 2019 general elections when 78 women politicians made their way into the Lok Sabha out of the 700 women participating candidates nearly counting to 14% of the total strength. Moreover, 25 women secured a seat in Rajya Sabha out of the total strength of 245, making up to 10% of the total. Although the representation of women kept on decreasing in Rajya Sabha and was noted to be highest in 2014 i.e. 12.7% (See, the table below).

Fig. 2: Representation of Women in 17th Lok Sabha, https://www.prsindia.org/parliamenttrack/vital-stats/profile-newly-elected-17th-lok-sabha

Effectuating the data stated, the inference of the bogus claims of the political parties have been still sustained, as, there are minimal numbers of female candidates in the parliament and the “winning capacity” is vaulted by the patriarchal domination despite the guaranteeing of equality rights by the Constitution of India.

ELECTORAL RIGHTS TO WOMEN IN INDIA

India’s acclaim of perpetrating the equal representation to women in the parliament is under a steel sky; the boundaries of the patriarchy are gripped. Albeit the 73rd amendment to our constitution provided for 33% of reservation to women and allocated the 46% share in the panchayats. But, the amendment is not ascertaining equality to women or women empowerment, rather a ‘jugaad’ of proxies for male members in their families.

The population of women and man are equal in India i.e. close to 50%, despite which the electoral representation of women is near to “diminishing” as the seat allocated to the states is based on the population in The Lok Sabha, howbeit, the representation of women is not even close to the percentage of the female population of the country. When there is complete representation in the Parliament, better policies can be formulated, which would ideally result in better governance. A study by The United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research’s suggested that the inclusion of women in the government resulted in the better economic growth of the nation. For a better representation of the women in the parliament, they need to get up and come to the forefront to contest elections and come to a position of power to bring about a change. But such an act would require awareness in the society regarding the importance of female representation and its effects on the overall efficiency in the governance in the country.

VERITY IN REPRESENTATION OF WOMEN IN PARLIAMENT OF INDIA

India experienced less number of women representation i.e. 10.9% in the parliament in the year 2012, accordingly to mitigate the minimal participation of women, the country empowered reservation quotas in 1994. The 73rd and 74th Constitutional Amendment Bill provided for reservation of 33% of seats in local governments, panchayats, and municipalities for women. Following this, in 1996 the Gowda’s government (United Front government) proposed the 81st Constitutional Amendment Bill which provided for one-third or 33% reservation of seats to women in the Lok Sabha and State Assemblies. However, the bill got lapsed and was tabled several times. Recently, in 2008 the 108th Constitutional Amendment Bill or Women Reservation Bill which also provided for 33% reservation to women in Lok Sabha and State Assemblies was tabled and is yet to become a law. The debate of women’s reservation is running since 1996 from the 81st Constitutional Amendment Bill till The Women’s Reservation Bill (108th amendment) in 2008 and yet it remained a ‘bill’ ready to form an ‘act’. The proposed bill has no reasons for its delay, but the hurdle of the social agenda of “democratization” in the country provides a controversy to the women’s reservation bill.

However, the bounds by the concepts of “democratization” was overturned in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, when the “winning capacity of women” flourished as the winning ratio of women counted to 14% and whereas participating candidates were only 8%. Thence, the inference of winning capacity landed in the favor of women. Thus, the 2019 Lok Sabha Elections is justifiable in descrying reservations to the women in politics.

CONSTITUTIONAL RECOGNITION OF WOMEN IN INDIAN PARLIAMENT

The Constitution of India has guaranteed various equality/equity rights to women and also empowers a duty on every citizen under Article 51A to abolish the practices of “derogatory to the dignity of women”, further, provides for reservation of not less than one-third of the total number of seats in Panchayats and Municipalities to women under Article 243 D(3) and Article 243 T(3), also provides for a reservation to women which is not less than one-third of the total number of officers of chairperson in the Panchayat and Municipalities at each level.

The reality of women’s equal representation was outspoken in 1996 in form of the 81st Constitutional Amendment Bill which provided for one-third reservation of women in the Lok Sabha and State Assemblies but was sabotaged under the Indian Politics Tornado. Thus, empowering a barrier to the electoral representation of women thereby, allowing the feminist theories in actualizing their effect on the ideas of democracy and political equality in regards to women’s representation and not providing equality in the sphere of political efficacies. The women’s voice against equal representation in India was resulted positive as The High Court of Bombay decided in the favour of the reservation of seats for women in the election of Jalgaon Municipality which was provided under the Bombay Boroughs Act 1925. Still, the identification of women in politics remains depressed despite the provisions of gender equality in the Constitution.

Conclusion

The 33% or the one-third reservations of seats to women was been lapsing since 1996 and yet recently has been tabled in 2008 which also landed into a dearth of dirt. This gives rise to the concept of ‘inequalities on established equalities’ as the constitutional framework guarantees equality but the social inclination of the country sweeps the ‘political equality’ as, the implementation of women representation in Indian politics challenges the hidden “verity of democratization” and the bill of women representation in Indian politics succumbs itself under the myth of “verity of democratization”.

As the lapsing of the women’s reservation bill is actuated to the constitutional amendment which is controversial under the supporting and opposing pillars of democracy.

But, the bleak truth has never been catechized, even though the women representation is diminishing, yet, the interminable roles professed by the women politicians are beyond comparison to men’s political efficacious.