At the risk of making a generalization, it could be said that corruption has its ultimate source in human greed, but also sometimes in necessity. If a man steals the proverbial loaf of bread because he has starving children, we will be inclined to condone the act of small theft. Some amongst us might even find it praiseworthy! Starving children is an extreme example perhaps, so let’s consider instead the case of a person who doesn’t earn enough to pay the school fees of his children – who starts taking bribes. Fewer amongst us would accept the moral if not legal defence of necessity in such an instance, arguing that it will otherwise be well-nigh impossible to determine where necessity ends and greed begins.

Is this a fair position? Surely a man can be said to be governed by a kind of necessity when he doesn’t earn enough to pay for the school fees of his children even if he is able to provide them with adequate nourishment. We are on a somewhat slippery philosophical slope, but an argument could nevertheless be raised that there is something that may not be ‘necessity’ stricto senso but something ‘akin to necessity’ – which can be clearly distinguished from pure and naked greed.

Bad policies and governance often breed low-level corruption. An example of corruption fuelled by necessity but created by bad policy is not difficult to find.

For example, there are government authorised shops that sell kerosene. In the past, there have been instances where the commission or profit a fair-price shopkeeper received was woefully low. For every litre of kerosene, the shopkeeper would earn ten paisa, an amount so low that even beggars would refuse to take it (assuming that it was possible to get hold of such a coin). Now, if a kerosene dealer is given ten thousand litres a month to sell, on such a paltry commission, he could only earn Rs 1,000 per month, obviously not enough for him and his family. By introducing a flawed commission rate the government was, in a sense, pushing thousands of shopkeepers towards corruption. Aside from flawed pricing, inordinately low wages can also foster corruption. For instance, underpaid clerical staff, be they in the courts, in municipal government or elsewhere will be more prone to the taking of bribes. We must first try and provide them with a fair wage that allows them to take care of their essential needs and those of their family. Once such fair wages have been provided and we then introduce strong anti-corruption measures they are likely to be far more successful. In other words, it is necessary to first create a climate in which anti-corruption measures have greater chance of success.

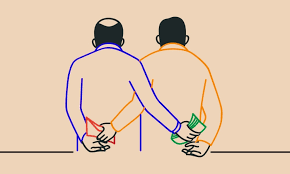

Sometimes there are entire government departments that are corrupt? How does such a phenomenon get created in the first place? A man may start off being corrupt due to necessity but when he finds that there is little or no risk of punishment, (and also that his office is full of other people who don’t hesitate in being corrupt), he too is emboldened to be corrupt. And so, corruption becomes a way of life. There is a certain kind of safety in numbers. A man tells himself that if everyone in the office is corrupt starting from the head of the department down to the chaprasi – what can anyone possibly do against them? Can they arrest everyone in the building? Impossible, he tells himself. Staff inside a corrupt department decide to protect each other – because they know that if they don’t do that, aside from a source of additional income drying up, no one might come to protect them. In corrupt departments honest officials might often find themselves in a soup. Why and how can this happen? This is because in some kind of Kafkaesque drama, all the corrupt officials decide to gang up to implicate and get rid of that one honest man!

There is a line in the minds of men that separates necessity from greed. An individual may draw the line differently from where others draw it, but everyone accepts that such a line exists. As far as absolute necessity is concerned, even if there are laws providing for extreme punishment, fear of punishment may not be enough to stop our man. So, in our example the man who has starving children at home may fully well know that he might be caught for stealing bread – but may nevertheless go ahead. The man who takes a bribe so that he can pay the school fees of his children might feel similarly; he may take the bribe even if there is well-oiled and efficient anti-corruption machinery at work (clearly not the case in India at present).

Fear of punishment is likely to be a more effective deterrent with respect to those who are corrupt because of greed; it may not dissuade those who are corrupt because of necessity. If there is no fear of punishment, then unbridled greed may have its way. Therefore, it is also very important to have effective anti-corruption machinery and penal laws in place. We need a rapid dispensation of justice. Do we have such a system? That is, of course, a purely rhetorical question to which everyone knows the answer. Our legal system churns so slowly that in civil matters, cases are filed by one generation and verdicts received by the next. Criminal justice is not much better in terms of speedy verdicts.

Should we be so concerned about low-level corruption? Isn’t it better to go after the big fish instead? For one thing, the two are not mutually exclusive. Secondly, it is low-level corruption that the common man most often encounters that causes him great harassment and heartburn. Finally, and most importantly pervasive low-level corruption creates a climate and chalta hai mindset that it facilities the crimes of the bigger fish in the pool.

Rajesh Talwar is an author of 36 books across multiple genres, and has worked for the United Nations for more than two decades across three continents.