In an action that is widely regarded as a move to encourage industry and global capital investment in Haryana, the state government of Haryana has refrained from issuing notification in matter of making Hindi compulsory in the subordinate courts of Haryana, almost two months after the Punjab & Haryana court heard and disposed of a petition which pleaded before the court that this decision this decision was a violation of fundamental rights.

It must be recalled that Haryana state assembly had passed a bill in the assembly which directed the mandatory use of Hindi as the sole language for work, including judicial work in all civil and criminal.

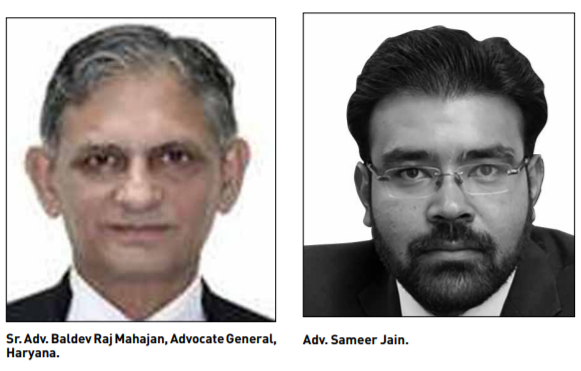

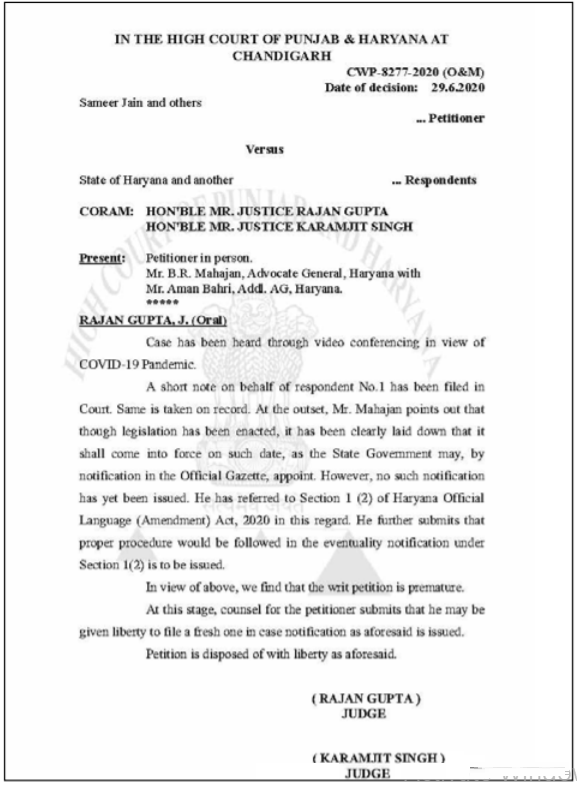

The state government, represented through Sr. Adv. Baldev Raj Mahajan, Advocate General for the state of Haryana, and Adv. Aman Bahri, Additional Advocate General for the state submitted before Justice Ranjan Gupta and Justice Karamjit Singh of the Punjab & Haryana High Court that, the legislation has been enacted, it has been clearly laid down that it shall come in force on such date, as the state government may, by notification in the official Gazette, appoint. However, no such notification has been issued, referring to the Section 1 (2) of Haryana Official Language (Amendment) Act, 2020. They further submitted that proper procedure would be followed in the eventuality notification under section 1(2) to be issued.

The bench presided by Justice Rajan Gupta and Justice Karamjit Singh directed the petitioners Adv. Sameer Jain, Adv. Sandeep Bajaj, Adv. Angad Sandhu, Adv. Suvigya Awasti and Adv. Ananat Gupta they have the liberty to file a fresh petition in case notification to make Hindi mandatory in subordinate courts is issued by the state government, and the petition was disposed.

Since the Haryana state assembly passed the bill making Hindi compulsory in subordinate courts, this issue is being keenly watched by majority of national and international businesses operating out of the state of Haryana. The petitioner had moved the Punjab & Haryana High Court after the state government passed an amendment section 3A of the Haryana Official Languages Act 1969, whereby Hindi has been designated as the sole official language to be mandatorily used for conducting all work in the civil and criminal courts of Haryana.

Aggrieved by the violation of their fundamental rights, the petitioners moved the Supreme Court on June 8, 2020, the court recognised the difficult created by the amendment, and permitted the petitioners to withdraw the petition and approach the Punjab & Haryana High Court.

The writ petition challenging constitutional validity of the Haryana Official Language (Amendment) Act, 2020 was listed before a three-judge bench of the Chief Justice of India Justice Sharad Arvind Bobde, Justice A.S. Bopanna J. and Justice Hrishikesh Roy J on 8 June 2020. The petitioners said that their amendment making Hindi mandatory impinged their fundamental rights under Articles 14, 19 and 21 of the Constitution of India. The Petitioners argued that mandatory imposition of Hindi creates an arbitrary and unreasonable discrimination against such advocates who are not proficient in the Hindi language and adversely affects their right to freely practice the legal profession before any court in India.

Chief Justice Bobde said that English can be used with the permission of the court. But petitioner Adv. Sameer Jain pointed out that the amendment had barred the use of any language other than Hindi, following which the Apex Court was ready to issue notice, but Haryana Additional Advocate General Arun Bhardwaj argued before the Supreme Court out that the law under challenge was a state law and it would be better if the Punjab and Haryana High Court dealt with it. To which the petitioners responded that their right under Article 19(1) (g) and Article 14 of the Constitution to freely practice law without discrimination is being hampered. Hence the Supreme Court is the most convenient forum due to Covid-19 lockdown as the petitioners too reside in Delhi and Noida. The Supreme Court directed the petitioners to approach the High Court but gave them the liberty to approach the apex court in future, if required.

“The exclusion of English will create practical hurdles for industries and corporations in the state of Haryana, especially in the commercial hubs of Gurugram and Faridabad, as well as commercial advocates and judges, most of whom obtain their legal training in the English language,” said Adv. Sameer Jain.

While industry representatives like Rajinder Kumar, General Counsel and Company Secretary Indus Towers, said, “The discussion is whether in the state of Haryana, should work in sub-ordinate judiciary be done only in Hindi, I gave it a thought and felt, it should be bilingual. With Article 343 (1) the constituent assembly adopted Hindi language along with English as official language on September 14th 1949, for the whole county. Even the official languages Act 1963, amended in 1967, allowed bilingualism, which is English along with Hindi. Our country is an amalgamation of states. According to Article 348, English can be used in the Supreme Court, High Court, also bills passed by the state legislature and parliament have to be in English along with other languages. This means, the new amendment by the State of Haryana says that all other work regarding law in the government can be in English too but the court should function in Hindi only”

Rajinder Kumar added that Haryana Official Languages Act, 1969, as original, was amended in 2020, the subsection 5 of the act said that unless the state government directs, by notification, English language can be used in addition to Hindi for legislative work in the state. Section 5 says English will continue to be used in addition to Hindi. Hence English will be allowed for legislative work but not in courts.

“Lawyers from Delhi, Noida, Ghaziabad and other areas of National Capital Region (NCR) travel to Haryana and file cases in the courts there. For all new lawyers graduating in law, Hindi is not even in optional language. Most lawyers are unable to argue in Hindi. The logic which they give when they pass the law, all their statements pertaining to evidence will be recorded in Hindi, but that too will be a problem for a large number of people as Haryana is a cosmopolitan state, were people from all over India and the world live,” said Rajinder Kumar.

English is widely used even in subordinate courts, there is no reason, why it should not be there at all. Idea is not to deprive those who don’t know Hindi. When you make Hindi mandatory, it is a kind of discrimination, between lawyers who speak Hindi and who don’t speak Hindi.

“The mandatory use of Hindi to the exclusion of other languages, especially English is bound to have inimical ramifications for commercial transactions and legal disputes arising therefrom. It will saddle the in-house legal teams and external counsels with the burden of gaining proficiency in the Hindi language and expensive translation and ancillary costs. Pertinently, English is invariably the language of commercial lawyers and adjudicators, a significant majority of whom have received legal training in the Queens language. The vast body of jurisprudence and literature on technical subjects and issues is also exclusively available in English and makes a vehement case for permitted use of English in commercial litigation in sub-ordinate courts of Haryana,” said Adv. Sameer Jain.

Pertinently, the amendment will also have a long lasting impact on the career of law students in the State of Haryana. The amendment will not only adversely affect students who are fluent in English, but will also harm the future of students who are comfortable in Hindi by impeding their practice before the higher judiciary.

It is likely that such a measure may have an unintended chilling effect on trade and commerce and calls for a clarification that use of English may be permitted as a matter of practice by the concerned Courts. Legally speaking, the amendment imposes a discriminatory and arbitrary qualification for all advocates and company professionals to be fluent in the Hindi language, thereby creating an unconstitutional impediment under Articles 14 and 19 of the Constitution of India. The amendment further unreasonably restricts the rights of advocates to practice before all courts and tribunals within the territory of India.

Once implemented, the effects of this legislation are likely to be felt strongly by corporate litigants in the state, especially the multitudes of companies carrying business and operating offices in commercial hubs of Gurugram and Faridabad. The supposed objective of the government action is to benefit Hindi speaking litigants in the state as they will have easy access to justice if judicial proceedings are carried and judgments are pronounced in Hindi. This will also ultimately fulfil the objective of promotion of Hindi as the official state language. While the objective seems sound in principle, it potentially casts a pernicious spell on the justice delivery mechanism by creating linguistic hurdles for corporations and legal professionals alike. The significance of prevalent use of English language for corporate communication including complex contracts as well as jurisprudence surrounding commercial laws has been belittled and may become an Achilles heel for all stakeholders.

Tarun Nangia is the host and producer of Legally Speaking.