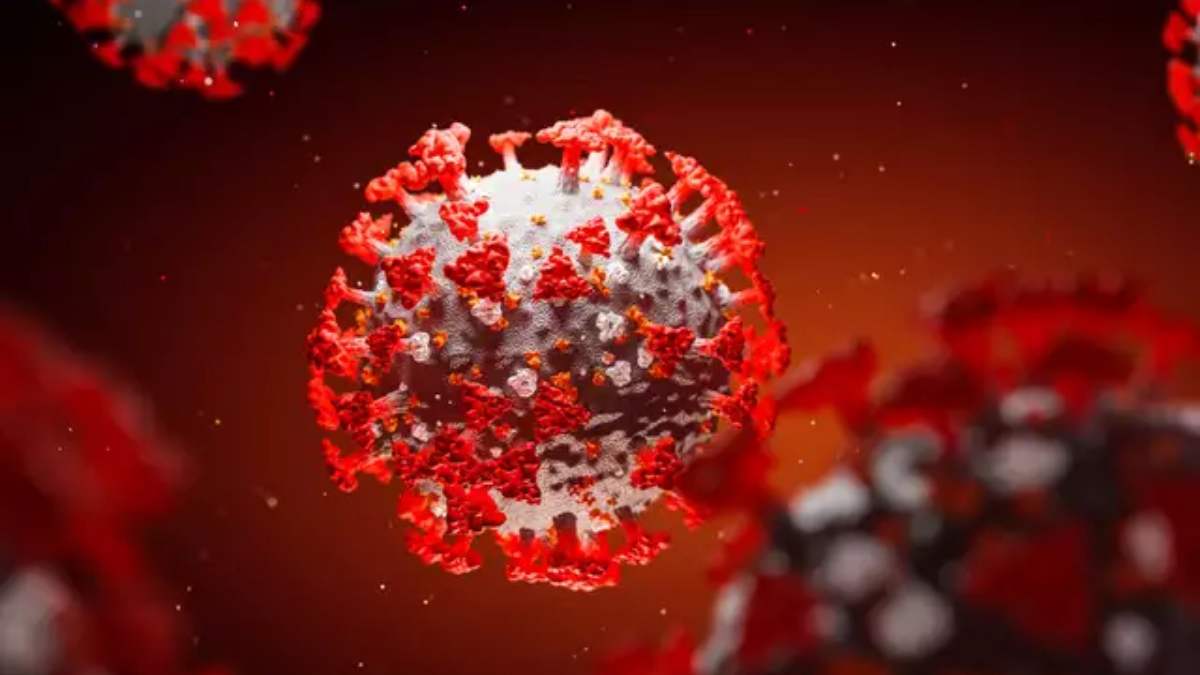

India is in the grips of the second wave of the deadly coronavirus and many cities are facing fresh restrictions and lockdown. We can say that India is now on the verge of a public health emergency. Most Importantly it is one of the world’s largest vaccine makers, however, it has had difficulty in immunizing its own population. Only about 13 percent of its population has undergone a single jab, with only about 2 percent completely vaccinated. The current Indian vaccination scheme provides vaccines to all citizens aged 18 and above. The citizens can get the vaccine by registering themselves on the online portal and reaching the vaccination centers.

The main point of concern in the current vaccination program is that it leaves out the elderly and the specially-abled, the people who are bedridden and cannot reach the vaccination centers. For the said concern, a Public Interest Litigation had recently been filed by two activists in the Bombay High Court. The PIL requested the Central Government to launch a door-to-door vaccination campaign for senior citizens above the age of 75, people with physical disabilities, and others who are bedridden. The plea further mentioned that if the elderly and specially-abled are deprived of the vaccination then it would constitute a gross violation of the right to good health under Article 21 of the Indian constitution.

RIGHT TO LIVE WITH DIGNITY AND GOOD HEALTH

COVID-19 vaccines are the lifesaving drugs of the citizens and especially the elder people who are comparatively more vulnerable to the coronavirus. This vaccination policy can be regarded as arbitrary and unreasonable as it deprives the elderly and specially-abled citizens who are entitled to protection under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. Bombay High Court while adjudicating in the matter of Dhruti Kapadia and Anr. V. The Union of India critically observed that “A policy which leads to such conclusion has to be viewed as arbitrary and unreasonable, for the elderly citizens are entitled to the protection of Article 21 of the Constitution of India as much as the young and abled-bodied citizenry of the country.”

Article 21 of the Indian constitution guarantees a person’s right to live with dignity and good health, which is inclusive of senior citizen’s right to live with dignity and good health. The Indian Judiciary has come to the fore to protect the same. Beginning from the 1984 case of Bandhua Mukti Morcha v. Union of India and Ors, courts have envisaged the Right to health under Article 21 of the Constitution. Besides that, the Supreme Court ruled in the 1996 case of Paschim Bangal Khet Mazdoor Samity & Ors v. State of Bengal & Ors that the primary duty of a welfare state requires the government’s obligation to provide adequate health facilities for its citizens.

In the landmark case of Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India, it was held that the right to live with dignity comes under the purview of the right to life under Article 21. Further, in the case of Mukti Morcha, the Apex court held that right to live with dignity under Article 21 is derived from Article 39, 41, and 42 of the Indian Constitution which are Directive Principles of State Policy. Though the Directive Principles are not enforceable like the fundamental rights, however, it is recommended that they should be kept in mind while framing the state policies.

Article 41 of the Indian Constitution ensures the elder people’s right to live a respectful and independent life by making effective provisions for their security. Moreover, in the case of Regional Director, ESI Corporation v. Francis De Costa, the Supreme Court held that security against sickness and disablement is a fundamental right under Article 21. Furthermore among its primary duties, Article 47 of the Indian Constitution directs the state to enhance public health, improve nutrition, and lift the standard of living. Improving public health is a critical component of this article. As one person’s right is associated with another’s duty, the right to health is directly proportional to the State’s duty, as determined in the case of State of Punjab and Ors v. Ram Lubhaya Bagga.

DOOR-TO-DOOR VACCINATION POLICY: THE ONLY WAY FORWARD

Moving forward, passing repeated orders to the Central Government to consider a door-to-door vaccine, the Bombay High Court asked the Brihad Mumbai Corporation(BMC) if the same could be implemented for people above the age of 75, the differently-abled, and the bed-ridden. In reply, BMC told the court that they would implement the scheme once subsequent guidelines are issued by the Central Government. However, the Central Government has been continuously opposing the policy by citing the effectiveness and the adverse effects of the vaccines, along with the problem of high wastage. Rebutting the above proposition, Justice Datta and Kulkarni observed “If indeed, vaccination of elderly citizens by adopting a door-to-door vaccination policy is being avoided because such elderly citizens are aged and suffer from comorbidities, we regretfully record that the elderly citizens are literally being asked to choose between the devil and the deep sea.”

Thus, Door to door vaccination can be an effective solution to address the aforesaid problem. This policy can ensure that the citizens who are above the age of 75 years or physically challenged or bedridden and are unable to get out of their houses to reach the vaccination center can be vaccinated effectively and efficiently. It can further solve the problem of the vulnerable sections of society, who live in remote parts of the country. In past, there have been many instances where door-to-door vaccination has proven successful. For example, the door-to-door eradication strategy of smallpox and polio in India was a big success which shaped up the structure of immunization efforts for the future. Though the situation is different in light of COVID 19, however, the idea of door-to-door vaccination could provide effective results. A similar stance was taken by Israel to vaccinate the majority of its population.

To conclude, A policy with such severe consequences must be considered arbitrary and unfair, since the elderly and specially-abled people are entitled to the security of Article 21 of the Indian Constitution just as much as the country’s young and able-bodied men. Thus, the above policy must be relooked upon in light of the arguments raised.