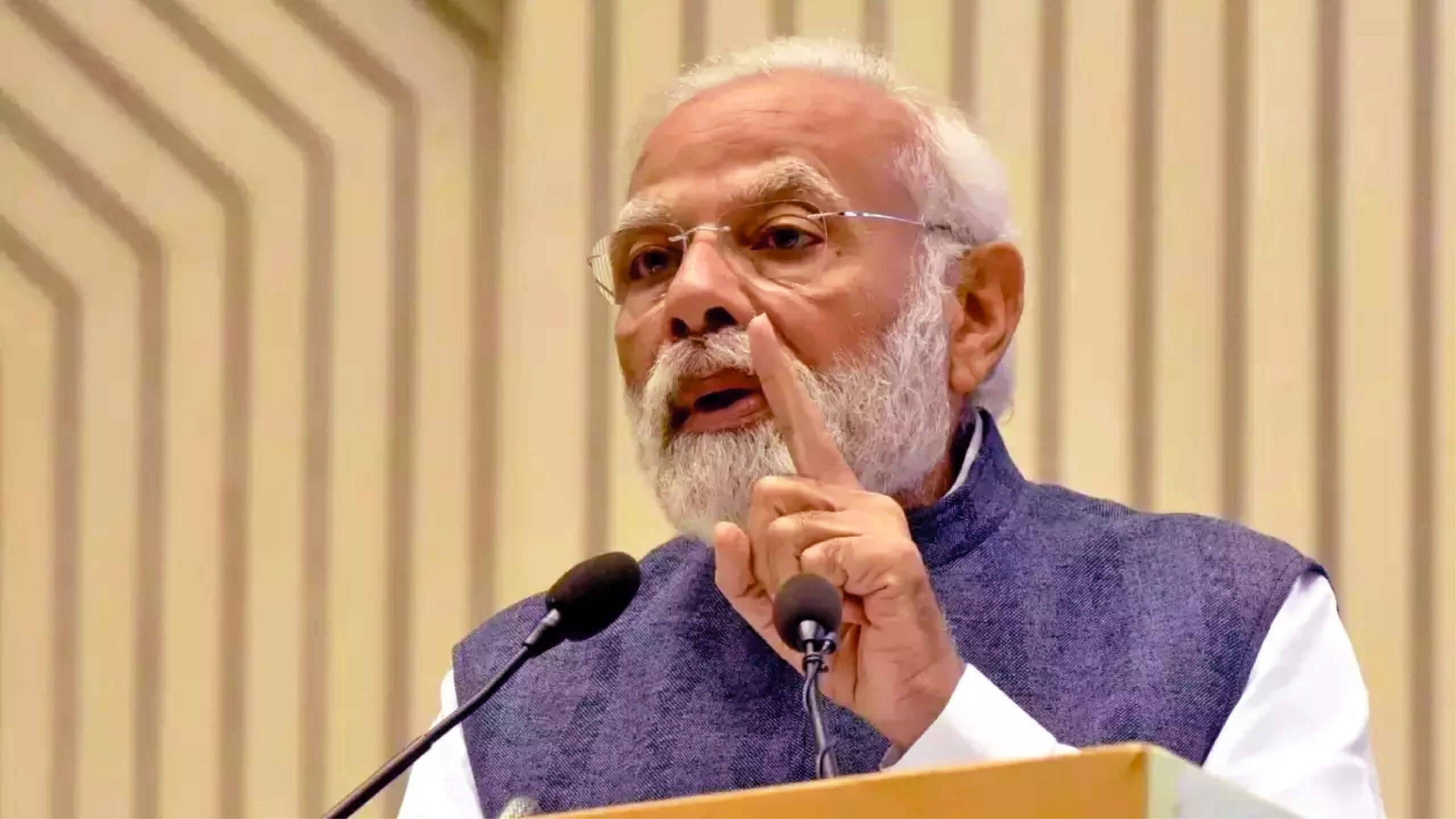

Prime Minister Imran Khan’s turbulent time at the PM office has finally come to an end following weeks of highly-charged political drama amid total constitutional chaos. On 7 April, the Supreme Court of Pakistan had delivered a verdict that had sought to disband and mandated a vote of no-confidence. As a face saving gesture, Imran had to quit or face even utter humiliation of being forced out.

Khan’s political party the PTI had lost the support of its key coalition allies, denying him the mandate required to stay in office. The second more compelling factor was that in recent times, he had fallen off the good books and lost support of the Pakistan military. In 2018, the military had helped him to come to power.

The Opposition parties secured 174 votes in the 342-member house in support of the no-confidence motion, the Speaker said, making it a majority vote. A significant number of MPs from the ruling party stayed away from the vote under mysterious circumstances.

In the recent months, the principal opposition parties of Pakistan had combined together to dislodge Khan as the coalition parties became more vocal and raised dissatisfaction against the present government. “As far as governance was concerned, the government had totally failed,” said Senator Anwaar ul Haq Kakar of the Balochistan Awami Party (BAP), a coalition ally that withdrew support for Khan in late March. The mood among the bureaucracy was also resonating as key members like Nadim Afzal Cham, the special assistant to the Prime Minister, resigned from his post and re-joined the opposition political party in early March.

The deep plummeting crisis of the economy has also been one of the key reasons for general resentment among the masses against the government. In February, following the announcement of cutting domestic fuel and electricity prices as the global rate surged, had a terrible effect on the economy. This added more pressure to Pakistan’s fiscal deficit and balance of payments as its currency fell to the historic lowest against the US Dollar. The State Bank of Pakistan was forced to steeply increase the interest rates as an emergency measure. Uncontrolled inflation, fertilizer shortage and local level policing were probably the last few straws on the camel’s back.

In October last year, the simmering civil military tensions exploded and reached new heights in public domain when Khan deliberately tried to retain the Lieutenant General as the head of the powerful spy division (ISI) effectively rejecting the nominee by Army chief General Bajwa. However, his nominee Lieutenant-General Nadeem Anjum, was eventually appointed as the new director general of Inter-Services Intelligence. The week-long standoff had sown the seeds of discontent with the influential military and the fragile political leadership.

With the recent tensions in Central Asia, Khan made a visit to Moscow to pledge allegiance to the Russian federation in its invasion of Ukraine. However, the military still had deep stakes with the United States and perhaps there could have been a bigger agenda to upset delicate balance. In response, Khan had alleged that the super powers are conspiring against him and as an evidence of the plot, he waved a letter in a public rally in Islamabad on March 27, claiming the US had delivered a diplomatic warning to Pakistan to remove him as prime minister.

Retired military official Air Vice-Marshal Shahzad Chaudhry suggested the tensions with the military also concerned Khan’s mercurial style of governing. Both defeated internally inside the parliament and battered outside, it is evident that Khan is probably on his last innings out. The cynical nature of the internal politics in Pakistan has however seen former Prime Ministers rebound back only time can tell us that if the captain gets a third umpire decision to reverse his dismissal.