But from a narrower prism, this action (the Rajiv government’s Shah Bano act) was seen as having angered Hindus who, from that perspective, were perceived as having seen it as an appeasement of Muslims. So, to appease the Hindus, the government decided, in February 1986, to unlock the gates of the Babri Masjid to the devotees of Lord Rama.

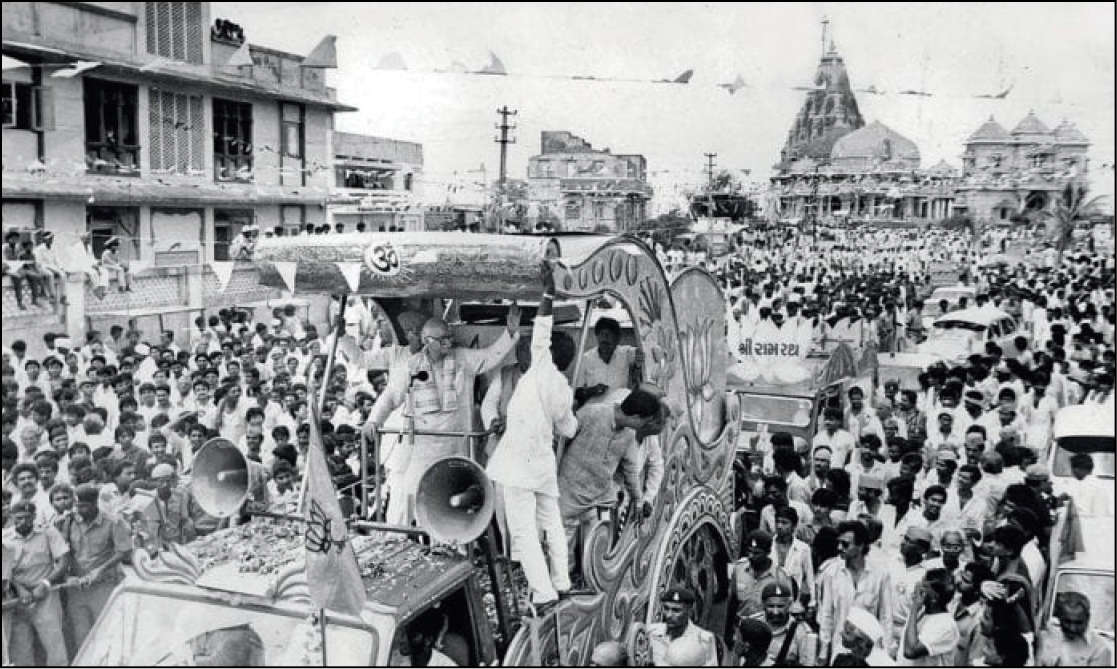

This was done through a local court in Faizabad vacating a stay order that had retained a status quo at the location in Ayodhya since 1949 when the mosque had become the site of communal confrontation. Was Rajiv Gandhi involved in the decisions leading up to this unlocking? Vir Bahadur Singh, the then chief minister of UP, denied his own involvement. But the fact attested to by many a witness is that that he was ensconced with Minister Arun Nehru in the state capital, Lucknow, deliberating this very case at the time when the sessions court actually pronounced the judgement. And this simple act of unlocking the access gate to a building already in long use as a temple—invested with the entire panoply of Hindu images and priests—was to vitiate community relations between north India’s two largest religious communities for the remaining years of the twentieth century, and usher in the twenty-first with a communal pogrom in distant Gujarat erupting from a massacre of kar sevaks in a train carrying them home from a pilgrimage to Ayodhya.

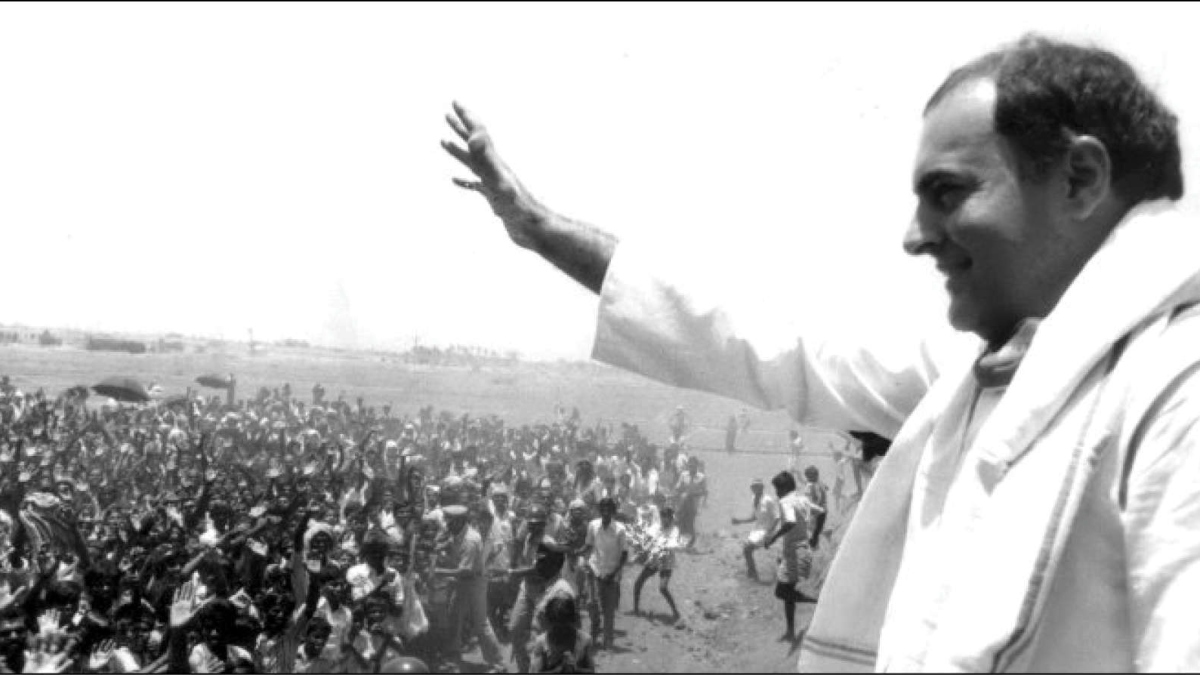

In September of that year, I found myself sitting opposite Rajiv in the PM’s cabin of his Boeing 737. The sparse monsoon of 1986 had petered out and we were flying to drought-hit Gujarat. I put to him a question that had been troubling me ever since February of that year with the ordering of the removal of the locks on the gates of Babri Masjid by the local magistrate, an order that had been complied with forthwith.

I realised of course that this was a political decision. Ever since the locks had been installed in 1949, the Masjid had ceased in fact to function as a mosque. While Hindu devotees continued to find access, Muslims were virtually excluded from entry into the precincts. But the idols installed in what had been the mihrab, the section of the mosque which would be equivalent to a sanctum sanctorum, the ‘magical’ appearance of which had triggered the locking of the gates, continued to so remain.

And although legally the entrance was secured, worshippers entered readily over a ladder surmounting the wall, with a regular mahant serving what had come to be used as a mandir. This situation had been engineered in 1949 by the District Magistrates K.K. Nayar and Guru Dutt Singh, both of whom went on to become active members of the Jan Sangh, the right-wing political entity that was the predecessor of the BJP. So the removal of the locks, and entry through the gate rather than over the wall, would have appeared only as an acknowledgement of a ground reality, besides getting the government credit for having taken this step to accommodate Hindu sentiment at a location, which—thanks to the vigorous promotion by right-wing religious groups and the aggressive advocacy of the Jan Sangh—had come to be, in the public’s mind, the very birthplace of Rama, the seventh incarnation of the God Vishnu.

As Belgian right-wing researcher and activist Koenraad Elst, in his article in Outlook titled ‘What If Rajiv Hadn’t Unlocked Babri Masjid?’ observed, ‘Fundamentally, this decision didn’t alter the Ayodhya equation. Architecturally, the building was and remained a mosque while functionally it had been and continued to be a Hindu temple. That is why in my opinion not taking this decision wouldn’t have changed the Ayodhya developments except in their timing. The different players, their strategies and resolve all remained the same. The Babri Masjid Action Committee and the Vishwa Hindu Parishad would have gone about their “business” just the same.’ This is an astute observation. Yet it was in its timing that the issue was to impact the country’s social harmony that was still slowly recovering from the trauma of Partition.

So my question to Rajiv was: ‘Since the removal of the locks was not going to change the status quo in any way, but would earn the support of sections of the Hindu community for your party, was it not realised that such a benefit could only be limited? After all, with the core of the Congress remaining secular, the development could not be exploited to its maximum, and the right wing would hijack the outcome, which it could trumpet as its triumph.’ That is what had happened.

Rajiv’s answer was direct and instant: ‘No government has any business to meddle in matters like determination of the functioning of places of worship. I knew nothing of this development until I was told of it after the orders had been passed and executed.’

I was, as might be imagined, completely taken aback. ‘But, sir, you were prime minister.’

‘Of course I was. Yet I had not been informed of this action, and have asked Vir Bahadur Singh [under whose watch, and under whose instructions, it was rumoured, the magistrate had taken this fateful—or shall I call it fatal—decision] to explain. I suspect it was Arun [Nehru] and Fotedar [Makhan Lal] who were responsible, but I am having this verified. If it is true, I will have to consider action.’ In the coming month, Nehru was dropped from the cabinet.

The author is a former chairperson of the National Commission for Minorities.