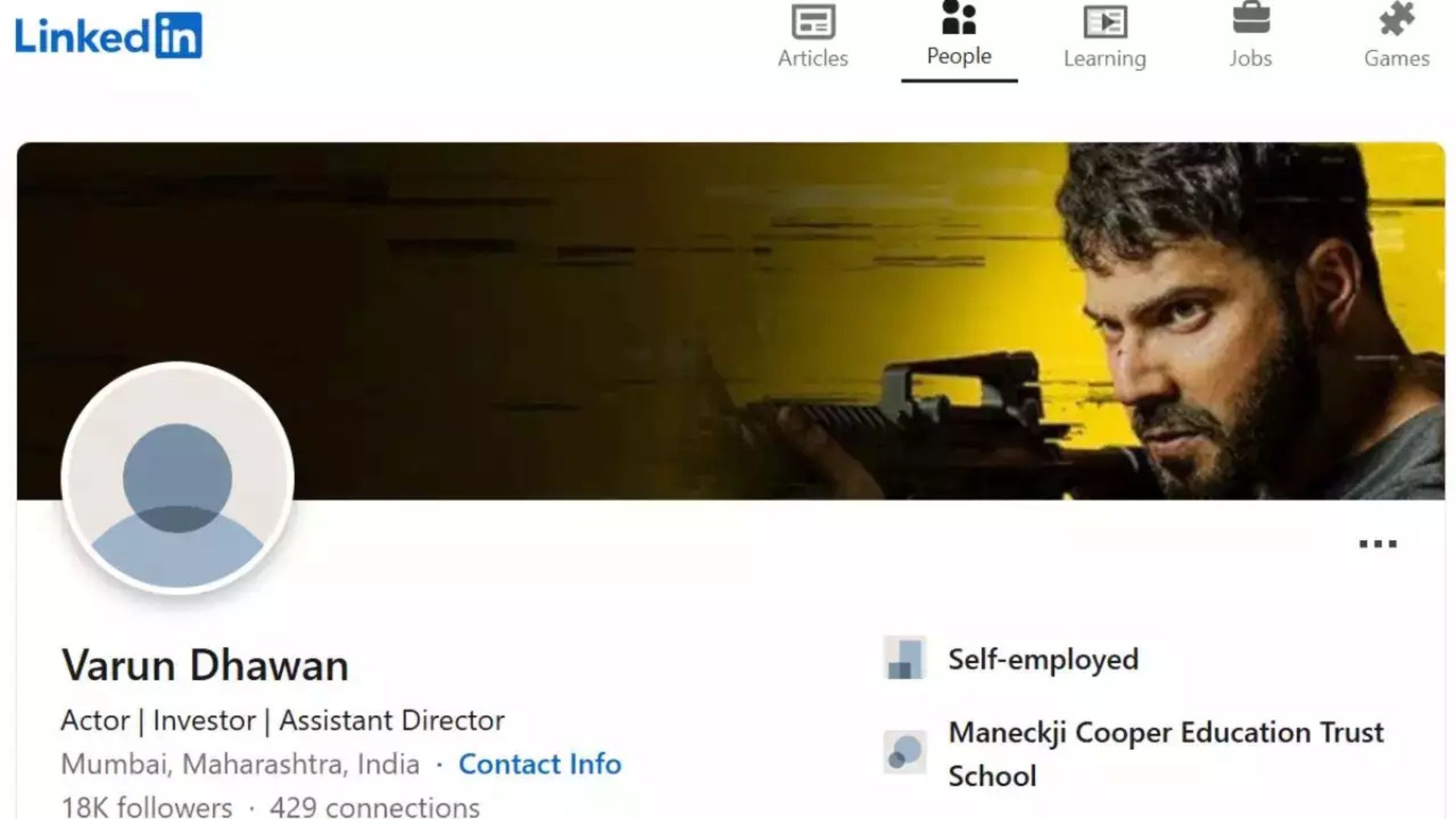

The empty main road echoes fragmentally with wails of ambulances. But this wail is different. It sounds like the wrenching away of the last thread of hope, of inexplicable suffering. It is visceral. It is human. As Covid-19 blazes through India at an unprecedented rate, almost every household has experienced that agony in some capacity. This pandemic isn’t just preying on the most vulnerable populations. So, it’s not invisible any longer.

The lexicon of the once unlucky is now a part of our daily vocabulary. As the death toll comes to weigh profoundly, it underscores the need for deep public and media scrutiny of the policy decisions regarding Covid-19 and our public health system. While we struggle to survive and breathe, it is worth wondering, is there any clarity in this catastrophe?

GETTING TO WHERE WE ARE

The number of infectious disease outbreaks has been accelerating, from HIV to Ebola to Zika. Public health experts had warned of potential pandemics and urged robust preparations since the first outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), yet Covid-19 still took large parts of the world by surprise. Globally, preparedness metrics failed to predict weaknesses —and the pandemic revealed certain fundamental deficiencies

There are few cases in which national health response capacities have been subjected to a rigorous stress test at this level. The Covid-19 pandemic response(s) were shaped by a series of insights, research findings, actions and reactions that took place amidst great uncertainty. Many of the choices made and decisions taken were highly time-sensitive — under conditions that changed unpredictably. The highest level of global alert, a PHEIC, declared by the Director-General of WHO on 30 January 2020, did not spur the worldwide response it should have. Neglect, indecision and confusion prevailed at the apex levels of all public health bodies.

This deprived us of perhaps the most essential commodity of all– time, earmarking the pandemic to spread across an unprepared world and an ill-equipped India.

AN INDIA PERSPECTIVE

Pandemics, cyclones and storms are acts of nature. The state of India’s public health infrastructure — lack of access to essential medical resources, fragmentation, and aversion to cross-sectoral cooperation —are not.

There were delays in coordinated and comprehensive action: beset by the long-standing undervaluing of health workers, acute underfunding, and an unscientific approach that denied the consequences of the pandemic.

The pandemic exposed the gordian knot that is the healthcare system in India.

In December, as China raised the alarm, the Indian government was preoccupied with its chronic ailments of religious fundamentalism and communalism in the form of the discriminatory Citizen Amendment Bill. Fueled by mass protests between far-right Hindu nationalists who supported it, and those who saw it as another mangling of the social fabric of the country.

India announced its nationwide lockdown eight weeks after Wuhan did. While the sheer immensity of 1.38 billion people being imposed in a nationwide lockdown dominated headlines, conversations and news reports, it served to camouflage a more catastrophic reality.

Nevertheless, despite a decrepit and funding-starved healthcare infrastructure, the country’s ability to manage the first wave of Covid-19 appeared laudable as the U.S., Canada, and European countries faltered under the second and third waves of the pandemic. Then things went awry. The turnaround raised false hopes that the virus had side-stepped India. Spurred in part by the cavalier attitudes that the country would be spared of a second wave, we weren’t afflicted just by the virus, but also by severe disillusionment and misinformation.

From the beginning of and even at the zenith of a national emergency, the Indian government remained focused on winning elections rather than actual governance. Amid a devolving crisis, the present Indian state has no means of ensuring critical scrutiny of the decisions that led to the current crisis. Distorted statistics prevailed, conveying a reassuring but false sense of certainty. Obfuscating the gravity of a pandemic is a dangerous path to a bigger disaster.

Now, all these decisions, policies and actions are overshadowed by the leaden smoke surging from funeral pyres that burn day and night, the gasps of breath of those with COVID-19 and the anguish of the millions who have lost their loved ones. Critical questions, such as why people are being forced to cremate family members in parking lots or on pavements, remain unanswered.

At the individual level, the onus lies with us, more than ever before, to ask ourselves: What does it mean for a majority of our population that lacks access to food, water and primary healthcare? Do statistics convey the reality for our overburdened and under-resourced healthcare system? How much value does life hold to not even be counted as a statistic when you die?

A CLOSER LOOK AT INDIA’S PUBLIC HEALTH SYSTEM

As early as 1946, India conceived a comprehensive plan for universal healthcare for all its citizens. Unfortunately, this vision is still to attain actuality.

At about 1.28% of its GDP, India’s spending on public health is one of the lowest globally. In a textbook illustration of market failures, financing of healthcare has continued to be dominated by regressive out-of-pocket payments.

Within its first year, the BJP reduced the health budget by around 15%, and its insurance scheme continues to be riddled with inefficiencies. An NHP in 2017 proposed raising health expenditure to 2.5% of the GDP by 2025. However, where these resources will come from remains unknown. Limited funding towards the health sector compounded by low efficiencies in public spending over decades have adversely impacted the reach and quality of health services. The result is deep inequities in regional distributions of health infrastructure and personnel.

While India has a growing private sector for health, the public sector operates at an incredible ratio of 0.008 doctors to 1,000 people. Most government health programs are implemented by accredited social health activist (ASHA) workers. Yet, they remain undervalued and underpaid. Rather than leveraging our human resources, there has been crippling neglect of adequate investment in community health workers, despite their necessity for any emergency response.

Moreover, India not only faces a double burden of disease but is also yet to overcome many of its “older” maledictions. Despite the country’s recent history with epidemics such as SARS, Japanese encephalitis, chikungunya, H1N1 and Nipah, the central government — responsible for controlling infectious disease spread — still lacks a concrete framework for disease control.

Even today, almost 2.4 million Indians die of treatable conditions yearly. Despite having the world’s most extensive nutrition program, 25 million children remain malnourished. Tuberculosis, dengue and cholera continue to claim lives each year- disadvantaged sections invariably bear the brunt of these systemic failures.

One can argue that even with these shortfalls, we have made progress in areas like polio eradication, maternal mortality and child survival. But this silver lining is a cost at which we cannot afford to ignore the minacious dark cloud.

WHERE CAN WE GO FROM HERE?

Successful country responses heeded the evolving science; they quickly mobilised, trained and reallocated their health resources and workforce. System capacities were increased, with the rapid construction of makeshift hospitals and primary care support.

It has been proven beyond doubt that vaccinations work- they remain our single best option. A single day of lockdown costs the country more than Rs 10,000 crore. The government needs to do the math, put its political issues aside and figure out how to vaccinate at least 51 crore people, and fast.

Currently, the reach and extent of primary care facilities offer key opportunities. If effectively leveraged they play a crucial role in promoting and delivering Covid-19 vaccinations, reduce wait times, and alleviate patient volumes at hospitals.

Capacity building of ASHAS, ANMs and Anganwadi workers is needed to ensure continued access to essential services, especially for women. They can assist in the provision of preventative services and help build trust in vaccines and the health system through their grassroots networks. They could aid the design of an equitable Covid-19 vaccination strategy by fortifying existing systems like the AB-PMJAY.

The government launched the Arogya Setu mobile app (CoWin portal) for contact tracing and symptom mapping. This has the potential to be expanded for scheduling routine and timely access to care. It can be leveraged as an important starting point to build data for information systems and disease registries.

Encouraging electronic health records and synchronising existing reporting systems across health facilities—including the private sector—remains a key feature of any health reform strategy. The IDSP needs to be transformed to expand its coverage and data reporting quality.

Enabling a level of self-management at home through a streamlined, accurate and comprehensive health communication strategy will be helpful from both infection control and operations perspectives.

However, these responses remain stop-gap arrangements that may only temporarily bolster the response. The diversion of resources from other essential health services (like maternal and child health) will have long-term repercussions.

The way forward is not abandoning the system that has been emerging out of the NRHM/NHM, but strengthening it through sustained support in technical, financial and functional capacities at regional and national levels. We need to build health infrastructure that is effective and equitable, with increased accessibility and responsiveness. We need greater investment in our public health system to achieve Universal Health Coverage and to ensure system preparedness to withstand future health emergencies.

A genuine change in our public health system is long due. We simply cannot afford the human toll to return to the status quo.

AS WE ARE NOW: TOGETHER, APART.

Covid-19 has torn child from parents, husband from wife, grandparent from a grandchild. On stretchers, in car-parks, in corridors, tethered to ventilators, gasping for oxygen, sequestered in their suffering, hundreds of thousands of patients face death’s vicinage alone. This particular cruelty of Covid-19 shatters a fundamentally primal need.

Across cultures and geographical boundaries, what we crave in extremis is unvarying—an antidote to our fear and pain- the comfort of familiarity, a hand that says hold on. With Covid-19, suffering and death occur in a harsh world of absences with families sundered and the sick marooned.

It is important to recognise that many of these deaths could have been prevented, and many lives saved. Unfortunately, this is not a novel narrative for India. We have all known of the profound deficiencies and fragilities in our health system, but it was a reality many of us chose to vaccinate ourselves against for too long.

Frontline workers have been our soldiers on the ground in this Covid war. With no time to grieve, often lacking PPE, they have witnessed this pain every minute. As cases and deaths shatter records, foreshadowing what might be one of the deadliest times in our country’s history, the weight of this pandemic has its own share of trauma for them: the indiscriminate path of the virus, burdened by the lives they had to choose to save, with limited resources. An indelible mark will be left.

Civil society has come together in this time of crisis. This reaffirms empathy for suffering that may not be our own. It emphasises the indomitable human spirit that galvanises us to fight for a tomorrow to abate the pain and agony experienced today. That is the true silver lining; that is the clarity in this catastrophe.

We need continued collective action by civil society more than ever to promote behavioural changes that reduce the transmission of Covid-19, to share food, water, medication and other necessities with those suffering most. Right now, we are doing that in a way that reveals enormous dedication, tenacity and resolve.

We must realise that we have the power to demand changes from the systems responsible for serving us. Most importantly, perhaps, Covid-19 has made us reacquaint ourselves with the value of us: the individual, the community, the country. Never again, at the time when people need each other most, can we allow a disease to pry us apart. We must remember that right now, even when we are torn — we still can be together, apart

The writer is a Communications Consultant for Public Health (Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation & William J Clinton Foundation). The views expressed are personal.