Muslims in India have lately been at their wit’s end trying to make sense of their past, present and future in this great nation. What should they believe? Whom should they trust? In what and to whom do they repose their confidence? Should they guide their perceptions and decisions on the basis of principles which define their nation or the treatment meted out to them by a certain section of their countrymen, the so-called fringe elements, which have lately been expanding rather rapidly?

The Constitution of India grants them freedom of conscience and equal right to freely profess, practice and propagate their religion, albeit subject to public order, morality, health and other provisions. It vests in them the right to conserve their language, scripture, and culture and promises protection against discrimination on the ground of religion, race, caste, language, or any of them. It guarantees them the right to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice and assures them that the government would not discriminate against any educational institution on the ground that it is under the management of a linguistic or religious minority.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been exhorting the nation to work towards “Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas, Sabka Vishwas, and Sabka Prayas”. More recently, he has called upon his party workers to engage with Muslims without any consideration to win their votes. Yet, their children are being deprived of scholarships and fellowships. Their religious educational institutions are experiencing existential threats—getting razed, merged, scanned for their sources of income and expenditure and closely monitored for their standards.

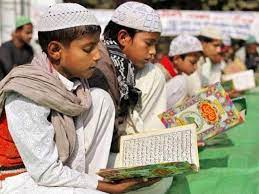

The National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR) has issued notices to all states and Union territories to conduct a detailed inquiry into government-funded and government-recognised madrasas that admit non-Muslim students. It has also ordered them to physically verify the non-Muslim students in these madrasas and ensure that they are taken out of their portals and admitted to formal schools. Ostensibly, the action is to act upon complaints that madrasas entice non-Muslim students by offering them scholarships.

The commission has invoked Article 28(3) of the Constitution which prohibits educational institutions from compelling children to take part in religious instruction without the consent of the parents. The Commission is vested with the responsibility of protecting child rights and has to discharge its mandated responsibility. Let the facts come out, but common sense suggests that no gurukul, madrasa, pathshala and schools would be admitting students without the explicit consent of their parents/guardians.

At the same time, no parent must be deprived of their right of getting their children educated in institutions or systems of education of their choice so long as that institution or system of education works within the framework of the Constitution and operates in accordance with the law of the land.

Article 30(1) of the Constitution of India gives linguistic and religious minorities a fundamental right to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice. Exercising their rights under the Constitution, the religious and linguistic minorities establish and administer a large number of schools, colleges, and universities.

These are recognised by the National Commission of Minority Educational Institutions (NCMEI) but have not been restrained from admitting non-minority students. In fact, they are required by law to open their doors to all at least to the extent of 50% of their approved intake.

Madrasas literally mean schools, but are contextually understood as institutions offering religious teaching and instructions. They are as much, if not more, covered in the rights of minorities to establish and administer educational institutions.

A large section of Muslims has been opposed to the idea of accepting any government grants or support for madrasa modernisation. They wanted to be left alone and outside the purview and dictates of the government. To them, madrasas were intended to offer religious instructions to prepare Muslims to better follow their religion, understand religious texts, practice their religion and thus prepare themselves for the life hereafter.

If they had continued to serve this very purpose, only the most enlightened non-Muslims and that too as a rarer of the rare exceptions would want their children to study in any madrasas. Madrasa modernisation, with a focus on providing instructions in worldly disciplines of knowledge and skills, has made them look quite like schools. Government-aided and recognised madrasas follow government or madrasa board syllabi.

Quite a few of them have a sizeable number of non-Muslim teachers. In some cases, even the heads of madrasas are also non-Muslim. One should not be surprised to find instances where a Sanskrit Pathshala turns into a Madrasa in the other shifts. Interestingly, Muslims, often labelled as conservatives and fundamentalists, have hardly ever objected or taken offence to such practices. It is no surprise that the number of madrasas seeking government grants and recognition has multiplied in relatively a short period.

What could be a surprise is the complaints that madrassas are alluring non-Muslims to their fold. The complainants are probably making a mountain out of a molehill. If their grouse is about giving scholarships to non-Muslim students, these very people would have accused madrasas of discrimination if they had not been giving scholarships to their non-Muslim students.

This is not a one-off incident. Lately, madrasahs have been bashed badly both by the state as well as non-state actors. Some have been crowd-attached and many have been demolished. Several state governments have either stopped grants or have been threatening to do so.

They have been subject to close monitoring and reviews. It seems that vested interests are determined to make it difficult, if not impossible, for madrasas to exist and thus deprive Muslims of their educational, religious and cultural rights guaranteed under the Constitution of the country.

Religious minorities, including Muslims, are an integral part of India. They constitute close to a fifth of the national population and deserve to share as many national resources. Proven to be socially and economically poorer and more marginalised than the most deprived sections of society, they deserve a lot more for equity and social justice.

Many a scheme and development programmes benefitting religious minorities and Muslims have been withdrawn on one or the other pretext. These include the Pre-Matriculation scholarships up to class VIII and Maulana Azad National Fellowship (MANF) on the pretext that the scheme overlaps with other similar schemes. By doing so the centre might save Rs 738.85 crore annually, but would deprive 6,722 students the opportunity to pursue PhD degrees.

Thus all schemes, except the post-matriculation scholarship intended for targeted beneficiaries have been discontinued. Further, the schemes like USTAAD, Hamari Dharohar, Seekho aur Kamao, and Nai Roshni have all been merged into a new scheme called PM VIKAS (Pradhan Mantri Virasat ka Samvardhan). Also, the Pradhan Mantri Jan Vikas Karyakram (PMJVK) aimed at infrastructural development in identified districts with minority concentration now is run in only 90 districts as against 380 planned initially.

India is home to about 11% of the Muslim population on this planet. With 213 million, they account for about 16% of India’s population. No wonder, many would like to consider as the second-largest majority in the country. Their socioeconomic development is, in fact essential for the development of the nation as a whole.

Furqan Qamar, a former Advisor of Education in the Planning Commission, is presently a professor of Management at Jamia Millia Islamia. Views expressed are personal.