A rich patronage to performing arts was integral to imperial durbars. The journey of classical Indian music would not be so enriched if the erstwhile rulers did not have such a refined ear for music. Music known as ‘havelisangeet’ set foundations for dhrupad and dhamaalgayaki. While most of music played in the darbars has been relegated to shared history and verbal narrative, one master project of restoration is the one being led by the Maharaja of Kishangarh. It was in his father, Maharaja Sumer Singh of Kishangarh’s rule that the pre gramophone era of powerful voices filled the darbars of Jaipur, Jodhpur, Jaisalmer and Kishangarh.

As their thumris and dadras filled the air, Maharaja Sumer Singhji captured voices of legends like Lalitabai, Allah JillaiBai, GauharJaan Niyaz and Gauri Bai on his spool leaving an illuminating legacy for his son, the present Maharaja Brajraj Singh of Kishangarh to revive. Years of restoration and sound correction, the meticulous removal of moisture from neglected tapes and the careful exclusion of ambient voices later was born this inimitable body of work.

The singing stars of this era were many: Naseem Bano who spent two years in Rampur in the as well were born nightingales who took khayalgayaki to a new realm, blending it to the lilting notes of folk music, thumris and dadras. The royal courts were resonant with the voices of legends like Lalitabai who lit up the Kishangarh courts with her music. Allah JillaiBai rose to fame under the patronage of Bikaner while Gauhar Jaan Niyazi was the jewel of Jaipur courts and Gauri Bai sang in Umaid Bhawan.

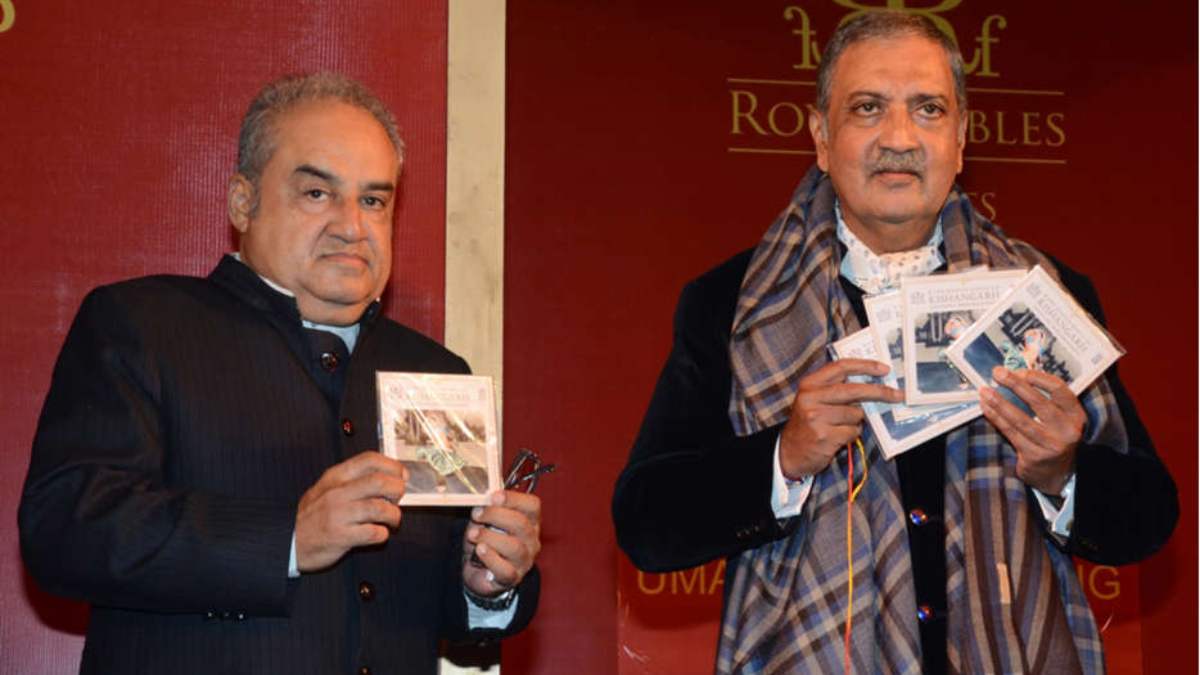

Music revivalist, Maharaja Brajraj Singh of Kishangarh revived the legacy of music that filled the royal courts of Rajasthan in the past which included the melodious renditions of semi-classical and folk court music include genres like thumri and mand singing style. In a freewheeling conversation, Maharaja Brajraj Singh shares his lilting legacy.

Q. What were the challenges faced by you?

A. These rare voices have been captured and preserved over the years. It took me three years to get it right! I remember how mesmerising it was when Gauri Bai sang at my wedding and it felt like the right thing to do to keep this legacy going forward.

Q. Rajasthan is known for its beautiful colours, its music and its craft. Dance is integral to its legacy. How do you connect your latest compilation of dance music to this rich culture?

A. Dance music dates back to the colourful Gangaur festival, observed throughout Rajasthan, as a celebration of Shiva and Parvati. During this time the ladies call upon the gods for their protection. The women take to singing and dancing the ghoomar, which has many versions. There is even a Gujarati ghoomar that has the beats of the garba but the singing has a Rajasthani accent. My father encouraged the women of Kishangarh to take up this dance form. This then turned into a 3-day festival for which the women practiced for months. My compilation of Rajasthani dance music is inspired by these dance performances. The album has an earthy, traditional sound that adds a nostalgic touch to the music belonging to the royal era.

Q. Has anyone in your family learnt any form of classical dancing?

A. My aunt learnt Kathak and was fond of dancing, but the women from the royal family were not allowed to dance in public. They had to cover their heads while dancing with a ghoonghat and dancing in public was not considered socially acceptable. However, they did teach this form to other women.

Q. The dhol that we hear in your music CD has a soulful and beautiful quality to it and does justice to the beauty of pure Rajasthani music; the instruments have a distinct quality that give to the music a trancelike feeling, and bring back the riches of music that your father wanted to maintain. Can you tell us a little about a few of the musical instruments that were used?

A. The instruments that were integral to Rajasthani dance music were the dhol, which was used for the purpose of dancing, and the bankiya, a very interesting instrument because it is very challenging to play. It is like a trumpet, which adds to the whole sound. These are accompanied by a harmonium and majeera, which are essential in Rajasthani music. My father loved music and dance, which is what inspired him to start this whole concept in the first place.

Q. You have featured iconic singers like Allah Jillai Bai in your album. Were there any recordings at that time?

A. At that time, the instruments used were very simple and limited, like the harmonium, sarangi, manjeera, bankiya and dhol, and the singers used to play with a specific group of musicians. They wouldn’t get musicians from outside so there were no recordings of the same at that time. It was all more about the performance. I can proudly say that this dance CD is the finest quality that one could possibly get of that time and it caters to an audience that would truly respect this music.

Q. Are there any fond memories that you can recall from that time period?

A. In Rajasthan people live in communities and take up professions like cooking, singing, dancing etc. No one breaks out from their traditional heritage, roots when it comes to talent. This talent is passed on for generations. I remember the jaats and gujjars coming to Kishangarh, they too inspired the dance. The audience always loved what they saw and the performances were truly great and memorable.There was also this story about a princess of Bundi who married the Maharaja of Jodhpur in the late 1800’s. She composed a particular version of the ghoomar that is still extremely popular and now has many versions. For that time, she was very modern and had a commanding presence.

Q. Your father was a man of vision and a patron of the arts. Anything else that you can tell us about him?

A. Oh yes! He was an avid lover of living the great life. In those days, they all lived in style. I have films he recorded at the 1960 Rome Olympics. He filmed Milkha Singh live at these Olympics! He used to go for Wimbledon and was a huge fan. The quality of life then was very different from how it is now.

Q. Coming back to this dance CD, tell us what these songs are about and what inspired their creation?

A. In Rajasthan there is a song for every occasion. That is what makes this music so beautiful. Women sing when their husbands are away, they sing when their husbands return! Every song has a message, a beautiful one. Combining music with dance has been a thrill and keeping this tradition going forward is what I plan to do. One of the songs in the album, ‘Ghumoor’ has various versions but the famous one has been recorded and produced in this album. A princess of Bundi composed this version of the song in the 1890s. She was a farsighted and modern girl for that era.

Q. The way the folk community takes to music and dance is almost like fish to water. Was there a lot of folk music and dance at the time these recordings were taken?

A. When you look purely at folk music, it is a different genre altogether and is a form derived from classical music. I believe that folk music and dance music cannot have the same impact as that is created by classical music. Thus, it was a challenge to produce this music in the classical folk manner, which is not done anymore in this day and age. This is my way of contributing to the revival of classical Indian folk music and inspire the folk musicians of today to not forget their classical roots.