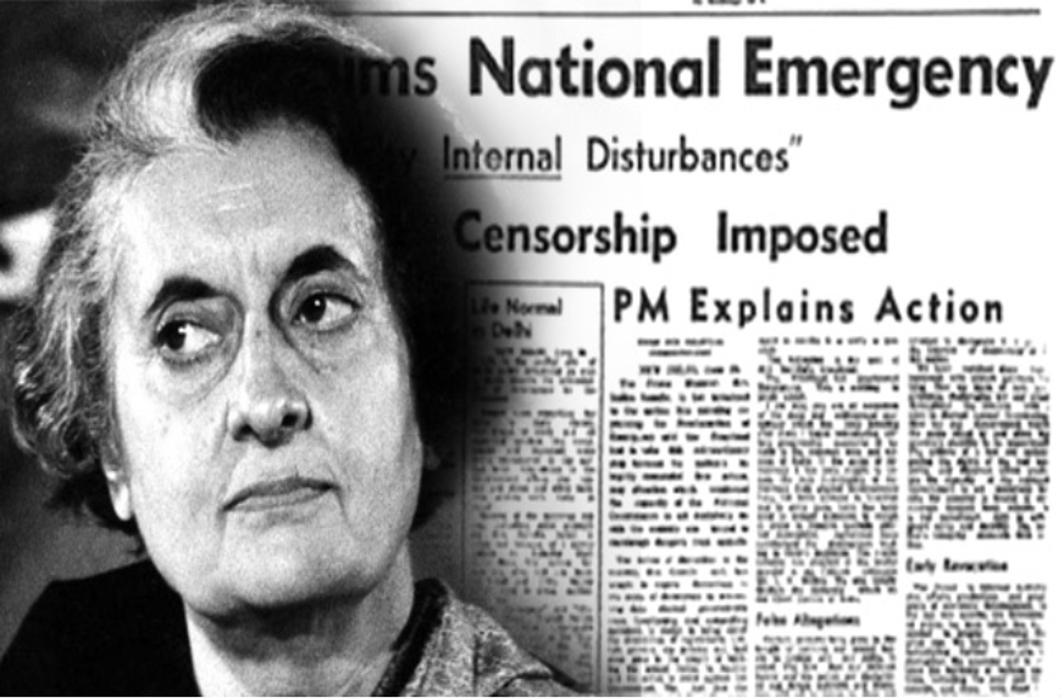

The Emergency took the nation unawares. Most senior leaders, including Jayaprakash Narain (JP), were arrested in the early hours of 26 June 1975. Censorship was imposed. In order to prevent newspapers in the national capital from publishing the news of the arrests, electricity was cut from newspaper offices. Motherland was perhaps the only paper that morning which could come out with a supplement. The editor, K.R. Malkani, had already been arrested, and those responsible for the supplement were nabbed too. Emergency is now a horrible memory. Even Mrs Gandhi realized that chapter could not be repeated and said as much after coming back to power in 1979.

Siddhartha Shankar Ray was the West Bengal Chief Minister and he, as it turned out later, was the main adviser of Mrs Gandhi in the imposition of the Emergency. He dealt ferociously with the Bengali press and its journalists. The Editor of The Statesman agreed that there could be no compromise on fundamental principles, but the censorship laws had to be generally obeyed, because the alternative was to shut shop. Even though submitting to censorship, we had to survive with dignity and with our principles intact. But the Delhi office was having a different kind of problem. It had published an edition in which the cuts in the news items were shown as blank spaces. It was disliked by the government, in particular by V.C Shukla who was the Information Minister, and hence responsible for implementing the censorship.

Mr S. Sahay, the Resident Editor of the Delhi edition of the Statesman told me about the pressures on the media. Mr Sahay recalled: “It happened this way. The censoring authorities in Delhi were maintaining the fiction that the censorship was not being rigorously imposed: what was happening was that editors were doing self-censorship. However, in fact the Press Information Bureau (PIB), was telephoning the newspaper offices and telling them what not to publish. The day the Supreme Court’s order (or judgment) in the election case was delivered, Dr Baji, the Press Information Officer (PIO), rang the editor up and suggested that, as a news item, the court verdict should be underplayed and that there should be no critical editorial on the subject. I told him that this was simply not on. The report from the legal correspondent was prominently displayed on page one; it was the main story and the editorial. Retribution was swift. The editor was asked to submit our pages to the censoring authorities. They would make cuts and delay the pages long enough to frustrate the publication of the paper the next morning.”

It was as a protest against what had happened during the Emergency that those believing the freedom of the press got together and formed the Editors’ Guild of India.

The Emergency regime decided to merge all the four new agencies into one and call it Samachar. PTI was badgered into acceptance of the plan and the rest followed. Having wrested control of the news agencies, and making Kasturi of The Hindu the chairman of Samachar, the Emergency Government decided to favour this news agency alone for doling out news. Newspapers were just ignored.

As if this were not enough, V.C. Shukla started the weekly Rozgar, which compiled advertisement of jobs by the government and the public sector undertakings. The idea was to weaken the national papers financially. Not satisfied with the virtual takeover of the news agencies, the government struck a blow at the Indian Express. The proprietor, Ramnath Goenka, was neutralized, the editor, S. Mulgaonkar, removed.

The Statesman was under tremendous strain. a very concerted attempt was made to buy at least few shares of the company so that a director of government’s (read Sanjay Gandhi’s) choice could be put on the board. Then the pliable editors were persuaded to prepare a code of conduct for editors and other journalists. Seventeen such editors did present a journalistic code of conduct to the Rajya Sabha on January 8, 1976. Item no. 3 in the code of ethics read: “Journalists and newspapers shall avoid reports and comments which tend to promotes tension likely to lead or leading to civil disorder, mutiny, or rebellion. Violence must be condemned unequivocally.” Recall the fact that Jayprakash Narayan was publicly telling Governments servants, even the Army, not to obey the illegal orders of the Government and you realize what the Government was seeking to prevent.

Then there was item no. 13 which read: “Journalists and newspapers shall refrain from giving tendentious treatment of news of disturbances, involving caste, community, class, religion, region or language groups and shall not publish details of numbers or identity of group involved in such disturbances except as officially provided.”

The President formally signed the Emergency order around 7 am on 26 June 1975, though it had been enforced the previous midnight. The Prime Minister had staged a constitutional coup. Mr. B.G. Vergheese, Editor of Hindustan Times, recalled those black days: “After the HT’s 26 June supplement hit the streets, I returned home to freshen up. Within a few hours, the electricity supply to the HT and the Statesman was cut, and the Jana Sangh paper, Motherland, was shut down. Word had gone round at the instance of Kuldip Nayar, then general manager and the editor of UNI, calling on journalists to gather at the Press Club to take stock of the situation. Not all came. Fear had taken hold. Those there adopted a resolution deploring censorship and the manner in which it had been imposed, and appeal to the Prime Minister to reverse the order. Kuldip was arrested and lodged in Tihar Jail. C.G.K. Reddy, a friend and long-time newspaper management guru, was picked up from Delhi in connection with the so-called Baroda Dynamite Conspiracy Case. Inder Gujral, information and broadcasting minister, who refused to take orders from Sanjay Gandhi, was seen as too soft for the job by the PM, and made to switch places with the Minister of State for Planning, Vidya Charan Shukla. Shukla swung into action without ado. He summoned leading Delhi editors to his residence and laid down the law. We had all known him as an innocuous functionary. Now, dressed in new authority, he revealed an iron fist as he led out the new censorship rules. With no hope of a restoration of electricity, I thought I might take counsel with my peers and called on other editors. Chalapathi Rau of The National Herald, a shoddy Congress organ, and Edatata Narayanan of the CPI-oriented Patriot, said the press had invited trouble through irresponsible and partisan writing. Girilal Jain of The Times also leant towards the establishment. S. Mulgaonkar, the editor of The Indian Express, was enigmatic. Ramnath Goenka, chairman of the Express group, was down with a heart attack in a Calcutta nursing home, and SM pleaded that he could not commit himself to anything that could cause Goenka further difficulties. Kuldip Nayar and Ajit Bhattacharjea were however raring to go. Blank editorials, blank columns, and quotations from Gandhi, Tagore, Lincoln and Jefferson, printed as our regular ‘Thought for the Day’, were soon banned. But stories of dictatorships in other countries, parables and book reviews with counter message continued to get past the censors. Reader got the message.”

Mrs Gandhi had long been convinced that independent organs of the press were hostile to the government. The rationale for censorship, of which she was the chief architect, assisted by Vidya Charan Shukla, Mohammad Yunus and an array of lesser functionaries and servitors, was spelt out in a speech she made in the Rajya Sabha on 22 July 1975.

Mrs Gandhi said: “Once there were no newspapers there was no agitation. The agitation was in the pages of the newspapers. If you ask why there was censorship of the press, this is the reason why. If nothing else has proved it, this has proved it. I have no doubt that had the newspapers come out and started inciting people, as they did before and as unfortunately they have done at times of communal trouble, then would have been a terrible situation. Our task was to avoid such a situation and we did avoid it.”

How was this done? Vidya Charan Shukla, in his very first meeting with Delhi editors, described the emergency as the beginning of a new era. In future, no “confrontation” would be permitted between the press and the government. He went on to explain that this meant the end of dissent and protest.

Censorship and news management were throughout arbitrary if not illegal. It was a mafia operation, enforced capriciously. Officials from the chief censor’s office would call newspapers and issue oral instructions about what should not be published or, sometimes, what the ruling coterie wanted published, and how. The chief censor was asked to convene to committee of editors to draft a model code of ethics that omitted reference to freedom of the press. Most of the editors resigned in disgust. Many journals and individuals were hounded. Thousands of others were denied access to printing presses, which were threatened if they dared accept to business from those blacklisted.

A vicious attack was mounted on the Press Council. Foreign newsmen were harassed and some were informed that they would be permitted to stay provided they took a “pledge” to abide by certain guidelines. Most declined. Some left. Yet, while pretending to be unmindful of foreign press coverage, the government was widely circulated through Samachar, often with some doctoring. Thus a long interview with Mrs Gandhi by Norman Cousins, editor of The Saturday Evening Review, New York, was re-circulated in India, minus certain passages.

The national motto, Satyameva Jayate, was eclipsed by dark forces, for twenty long months.