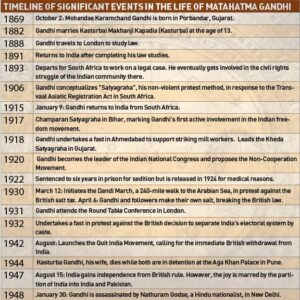

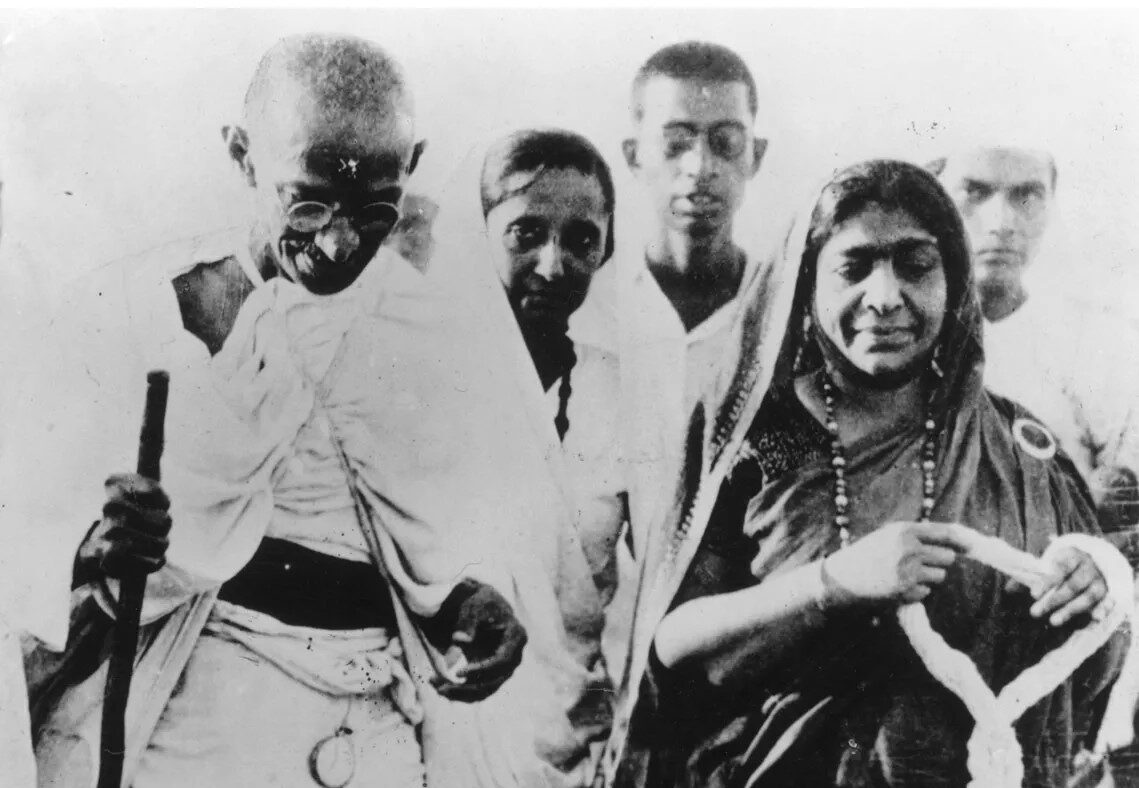

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, often referred to as Mahatma Gandhi, was born on October 2, 1869, in Porbandar, India, and passed away on January 30, 1948, in Delhi. He was a prominent Indian lawyer, politician, social reformer, and author who rose to prominence as a key leader in India’s struggle for independence from British colonial rule. Due to his significant contributions, he’s revered as the founding father of the nation. Gandhi’s commitment to non-violence, known as “satyagraha,” became a transformative tool for achieving political and societal advancements.

To countless Indians, he was revered as the “Great Soul” or Mahatma. The overwhelming love and admiration from the masses often overwhelmed him, making it challenging for him to work or even rest. As he once mentioned, the challenges faced by someone of his stature were only understood by those in similar positions. His influence wasn’t just confined to India; Gandhi’s reputation and legacy grew globally both during his life and after his passing. Today, the name Mahatma Gandhi is celebrated and recognized across the globe.

Gandhi’s Early Years: From Modest Beginnings to London’s Law Halls

Gandhi was the youngest offspring born to his father’s fourth spouse. His father, Karamchand Gandhi, held the esteemed position of the dewan (or chief minister) of Porbandar, a modest principality in what’s now Gujarat, India, during the era of British control. Although not traditionally educated, Karamchand was a skilled administrator, navigating the complexities of royal, colonial, and local needs.

Putlibai, Gandhi’s mother, was deeply religious, showing little interest in worldly adornments. She spent her days balancing between her domestic duties and spiritual practices. Young Mohandas was brought up in an environment rich in Vaishnavism, flavoured with Jainism’s principles, such as nonviolence and the eternity of all things. Consequently, values like ahimsa (non-harm), vegetarianism, and religious tolerance became integral to him. The educational infrastructure in Porbandar was basic, and Mohandas’ initial schooling was rather elementary. Fortunately, the family moved to Rajkot, where his father held a similar position and where better educational opportunities awaited.

Although Mohandas occasionally excelled in school, he was generally an average student with a notably poor handwriting. Married at 13, he took a year off from school. He was shy and didn’t particularly excel in academics or sports. Instead, he cherished solitude, took care of his unwell father, and assisted his mother at home.

During his teenage years, he underwent a phase of minor rebellions, engaging in acts that went against his family’s traditions. However, after every mischief, he would vow never to repeat it and, remarkably, he stayed true to his promises. Despite his outer simplicity, he had an innate drive for self-improvement, drawing inspiration even from legendary Hindu figures.

In 1887, Mohandas barely passed his matriculation exam from the University of Bombay and enrolled at Samaldas College in Bhavnagar. Adapting to English from his native Gujarati was challenging, making academic understanding a struggle.

As his family pondered his career path, Mohandas dreamt of becoming a doctor. However, to uphold the family’s stature in Gujarat, he had to pursue law. This required him to study in England. Excited by the prospect, Mohandas saw England as the heart of enlightenment and culture. The journey to England wasn’t straightforward: his family’s finances were tight, and his mother feared the moral dangers of the West. But through determination, familial support, and a vow to abstain from wine, women, and meat, Mohandas finally set sail in 1888. Soon after reaching, he joined the Inner Temple in London, one of the prestigious law colleges.

Gandhi’s Transformation in England and Challenges Back in India

In England, Gandhi diligently pursued his studies, focusing on improving his English and Latin by attempting the University of London’s matriculation exam. Yet, his primary concerns in London were personal growth and moral dilemmas rather than academic achievements. Adapting from the simpler life of Rajkot to the diverse culture of London was a challenge. He faced societal pressure regarding his choice of vegetarianism until he found a supportive community and literature, which strengthened his commitment. His involvement with the London Vegetarian Society provided him not only with confidence but also introduced him to influential thinkers. Here, he encountered diverse personalities, from humanitarians to Theosophists, who exposed him to the Bible and notably, the Bhagavad Gita in English. These interactions enriched his philosophical perspectives, which later influenced his political ideologies.

Upon his return to India in 1891, Gandhi faced unforeseen challenges. Grieving his mother’s demise and realising that his barrister degree didn’t guarantee success, he struggled professionally. After an unsuccessful stint in a Bombay court and being denied a teaching role, he headed back to Rajkot. There, even simple work like drafting petitions became unavailable due to conflicts with a British official. An unexpected opportunity in South Africa in 1893, though not ideal, provided a new direction for his journey.

Gandhi’s Formative Years in South Africa: The Rise of a Leader

In South Africa, Gandhi faced realities he hadn’t previously encountered. Over two decades, the continent threw challenges at him that reshaped his destiny, with two of his children being born there.

A Call to Action amidst Discrimination :Upon arrival, the racial prejudices of South Africa were immediately evident to Gandhi. He encountered blatant racism — from being asked to remove his turban in a Durban court, to being forcibly ejected from a first-class train compartment in Pietermaritzburg. Such regular indignities, typically accepted by the Indian community, instead ignited a passion in Gandhi. For him, these were not just personal offences; they were an affront to his identity and human dignity. This culminated in his profound realisation during a journey from Durban to Pretoria, marking the beginning of his stand against injustice in South Africa.

While in Pretoria, Gandhi endeavoured to uplift and educate his fellow Indians about their rights. But it was an unplanned extension of his stay, caused by the discovery of a bill proposing to strip Indians of voting rights, that truly cemented his place as a political activist in South Africa. Emergence as a Politician and Activist: Surprisingly, Gandhi, who until then had shown little interest in politics or public speaking, transformed into an astute political activist almost overnight. He became a voice for the Indian community, founding the Natal Indian Congress and ceaselessly advocating for their rights. His tireless efforts ensured that issues faced by the Indian community in South Africa caught international attention, with notable newspapers across England and India covering their plight.

During a trip to India in 1896, Gandhi garnered support for the Indian diaspora in South Africa. However, misinterpretations of his efforts ignited anger amongst Natal’s European populace. Upon his return, he faced physical assault but chose the path of non-retaliation, adhering to his belief of not seeking personal vengeance.

From Passive Resistance to Satyagraha: Gandhi’s stance wasn’t merely passive resistance. During the South African War, he believed in the duty of Indians to serve, leading to the formation of an ambulance corps. But post-war, the situation for Indians didn’t improve. A degrading registration ordinance for Indians in 1906 was the final straw. This led to the birth of “satyagraha” – a method of non-violent resistance against injustice.

The satyagraha movement in South Africa spanned over seven years, witnessing moments of both triumph and despair. Despite significant challenges, under Gandhi’s leadership, the Indian community exhibited immense resilience. Their peaceful resistance eventually brought the South African government to the negotiation table, resulting in a compromise brokered by Gandhi and General Jan Christian Smuts.

Upon leaving South Africa in 1914, Gandhi had not only left an indelible mark on the nation’s socio-political landscape but had also been transformed by his experiences. While his efforts didn’t bring a lasting solution to South Africa’s racial problem, the nation had been instrumental in moulding Gandhi into the leader and symbol of peace he would become in India.

Gandhi’s Spiritual Odyssey and South African Impact

From early years in Porbandar and Rajkot, influenced by his mother, Gandhi’s spiritual journey was deepened in South Africa. While his Quaker friends in Pretoria couldn’t sway him towards Christianity, they ignited his passion for religious exploration. Captivated by Tolstoy’s Christian writings, Gandhi also explored the Quran and Hindu scriptures. His interactions with scholars and personal studies led him to see the universality of all religions, though he acknowledged their human interpretations could be flawed.

Guided spiritually by Jain philosopher Shrimad Rajchandra, Gandhi grew appreciative of Hinduism. The Bhagavadgita, which he encountered in London, became a significant spiritual guide. Two concepts, aparigraha (non-possession) and samabhava (even-mindedness), resonated deeply, advocating a life devoid of materialistic attachments and emotional turbulence.

Beyond spirituality, Gandhi’s South African experiences moulded his professional ethics. In a notable 1893 case, he facilitated an out-of-court settlement, viewing his legal role as a mediator. Clients were more friends than customers, seeking advice beyond legal matters. Despite a lucrative legal career, Gandhi prioritised public causes, often investing his earnings into them. His homes in Durban and Johannesburg became hubs for young activists and colleagues. Drawn to a life of simplicity and hard work, Gandhi, influenced by John Ruskin’s critique of capitalism, established Phoenix Farm near Durban in 1904. Later, influenced by his admiration for Tolstoy, he founded Tolstoy Farm near Johannesburg. These communities set the groundwork for his future ashrams in India, like Sabarmati and Sevagram.

South Africa wasn’t just a political battleground for Gandhi; it was where he solidified his leadership style, characterised by fearlessness and commitment to principles. As Gilbert Murray noted, such a man, undeterred by worldly desires, becomes an indomitable force that leaders should approach with caution.

Gandhi: The Nonviolent Revolutionary and India’s Road to Independence

Mahatma Gandhi, often referred to as the ‘Father of the Nation’, played a pivotal role in India’s struggle for freedom. His unwavering commitment to nonviolence and justice propelled the country toward its goal of independence from British rule.

From South Africa to the Indian Subcontinent: In 1914, after championing the rights of Indians in South Africa, Gandhi decided it was time to return to his homeland. His journey took him to London for several months before arriving in Bombay in January 1915. Once back, he took a keen interest in understanding the intricacies of Indian politics and the depth of British colonialism.

Early Involvement in Indian Politics: Although initially distant from the political landscape, Gandhi’s perception began to change post-WWI. The Rowlatt Acts of 1919, which allowed the detention of individuals without trial, became a turning point. Gandhi, sensing the injustice, introduced the concept of ‘satyagraha’ or non-violent resistance. His methods were a blend of passive resistance and active resilience, aiming to shake the foundations of British rule in India.

One major incident that fuelled the fire of resistance was the Amritsar Massacre. British-led troops killed hundreds of unarmed Indians, and this brutal event spurred Gandhi to challenge British authority head-on. Through his guidance, by 1920, the Indian National Congress was transformed from an organisation of the elite to a massive movement that penetrated even the smallest towns and villages.

Facing Challenges and Stepping Back: However, the journey wasn’t without setbacks. In 1922, alarmed by a violent incident in Chauri Chaura, Gandhi decided to suspend the mass civil disobedience movement. He was later arrested and sentenced to six years in prison, although he was released in 1924 due to health concerns.

Upon his release, Gandhi found the political scene transformed. The Congress Party had divided into factions with differing ideologies. Moreover, the unity between Hindus and Muslims had started showing signs of strain.

Re-emergence in Politics and the Path to Independence: By the late 1920s, the political tempo in India had quickened. Gandhi re-emerged as a force when the British government’s Simon Commission, which lacked any Indian representatives, was boycotted by Indian parties. His continued endeavours, such as the Salt March in 1930, became symbolic acts of defiance against British oppression.

World War II brought another dimension to the struggle. Although personally against war, Gandhi recognized the precarious position the British were in. The Indian National Congress advocated for Indian self-rule in exchange for supporting the British war effort. The “Quit India Movement” of 1942 encapsulated this demand, leading to widespread protests and the arrest of key Congress leaders.

Post-war, as Britain’s Labour Party came to power, the tides began to turn in India’s favor. After extensive negotiations involving the Congress, the Muslim League, and British representatives, the Mountbatten Plan was devised. In August 1947, India was partitioned into two dominions: India and Pakistan.

Gandhi’s Final Days: The joy of impending independence was overshadowed by the tragedy of partition. Violent communal clashes between Hindus and Muslims erupted, leaving a trail of devastation. Gandhi, true to his principles, tirelessly worked to foster unity and peace. His efforts culminated in significant peace missions in places like Calcutta and Delhi. Tragically, these very efforts led to his assassination on January 30, 1948, by a Hindu extremist who believed Gandhi was appeasing Muslims.

In the annals of history, Gandhi’s legacy stands as a testament to the power of nonviolence and the indomitable human spirit. Through his life, he demonstrated that peaceful resistance could bring down even the mightiest of empires.