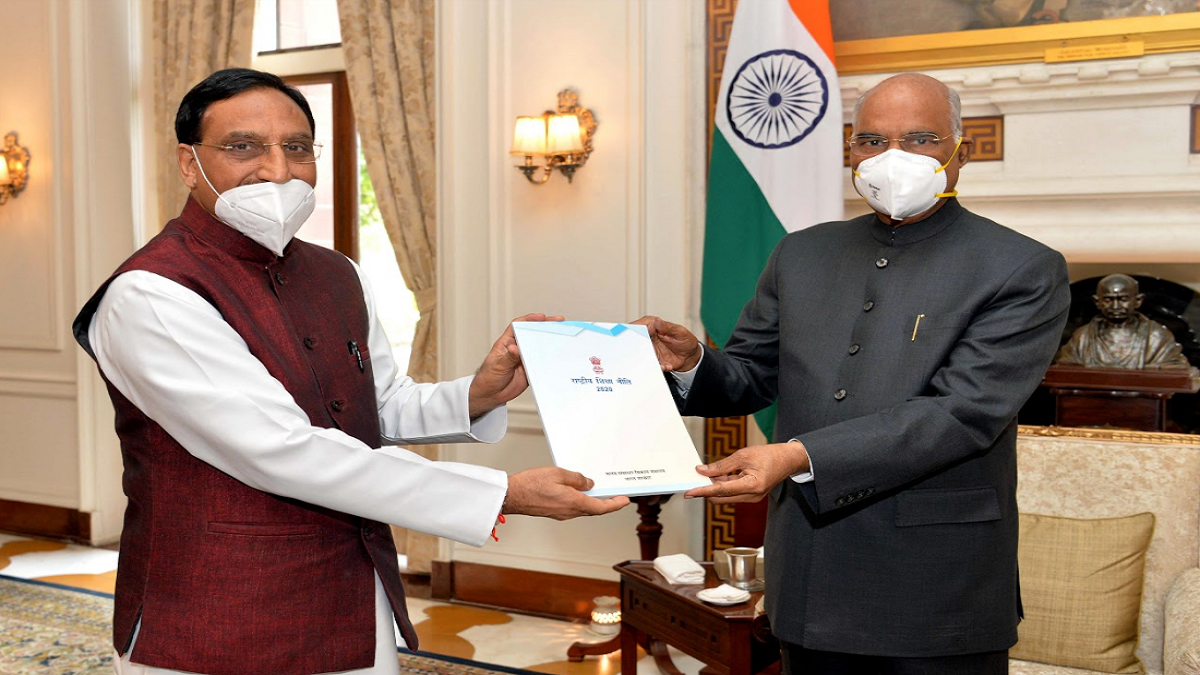

The National Education Policy 2020, prepared by the HRD Ministry for the consideration and approval of the Union cabinet and Parliament is a profound document as most of the ailments eating into the vitalities of the education system have been correctly diagnosed and prescriptions provided for. Now whether the country can muster the required political will and bureaucratic commitment and commit adequate financial resources to implement the policy in its true spirit or whether it will also meet the fate of the past two policies of half-hearted implementation is the real challenge. After all, lofty ideals and good-intentioned statements do not go beyond a point.

The HRD Ministry, now the Ministry of Education, has visualised a complete restructuring of the school as well as higher education institutional architecture, including policymaking, academic management, regulation and accreditation. School curriculum and pedagogy will be transformed to promote the development of creative and analytical thinking rather than rote learning. The policy document visualises “Four Stages of School Education”: the Foundation Stage, Preparatory Stage, Middle Stage and Secondary School Education. All stages of education have clearly defined objectives, which is appreciable. The commitment to quality Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE) has been re-emphasised, but the commitment to a nutritious breakfast along with mid-day meals in primary schools has been diluted, though appreciated in principle. To check early dropouts and learning deficits, one-on-one tutoring has been stressed upon. The need for filling up vacancies and appointment of adequate trained staff has been re-emphasised to improve the quality of education. For effective administration and optimal use of teaching staff and infrastructural facilities, the concept of school complexes will be operationalised. But no firm commitment has been made to extend the RTE Act-2009 from Pre-school to Class 12 covering all the school education, though the idea has been appreciated. The commitment to publicly funded neighbourhood schools has also been given a decent burial by a conspiracy of silence. Meanwhile, the threelanguage formula will be continued.

Teachers’ training will be accorded the highest priority to improve the quality of school teaching, for which it will consist primarily of a 4-year integrated B.Ed. programme, located only in multi-faculty HEIs. By 2030, dysfunctional independent teachers training institutions will be phased out. Appointment of teachers will be only on merit-basis. The harmful practice of excessive teacher transfers will be halted and local teachers having the commitment and knowledge of local languages and ethos will be preferred. Teachers will not be engaged for non-teaching duties and will be provided with opportunities for continuous professional development and career advancement.

Higher education will also be completely restructured, revamped and re-energised to provide quality education. As future employment opportunities will consist of skilled jobs of a creative and multidisciplinary nature, the education system needs to be responsive to these requirements accordingly. All Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) will be multidisciplinary institutions. The overall higher education sector will be integrated into a single higher education system, including professional and vocational education. Undergraduate education will emphasise on liberal arts education for which humanities and arts will be integrated with science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). Imaginative and flexible curriculum structures will enable students to opt for creative combinations of disciplines for study. Universities will offer high-quality undergraduate and postgraduate programmes. There will be three types of HEIs. Premier universities will be researchintensive, and other universities will put greater emphasis on teaching with a significant research component, and all colleges will focus on undergraduate teaching and will be autonomous degree-granting institutions. Single-stream HEIs and affiliated colleges will be phased out. Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) in higher education will be raised to 50% over the next ten years. Reservation policy in admissions will continue. The growth of both public and private institutions, with a strong emphasis on developing a large number of outstanding public institutions, will be facilitated. Access to high-quality institutions in disadvantaged geographical areas will be a priority.

HEIs and faculty will have the autonomy to innovate in matters of curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment, taking local conditions into consideration. Motivated, energized and capable faculties will be appointed and nurtured. Excellence will be incentivized through merit-based recruitment, promotion and salary increases. In-service continuous professional development for college and university teachers will continue in Academic Staff Colleges. Professional education will be integrated into the overall higher education system and the practice of setting up standalone technical institutions/deemed universities will be discontinued. A National Research Foundation will be established to nurture, promote and liaison for quality research in the country.

For effective governance and leadership, which will create a culture of excellence and innovation, high-quality leadership will be developed, and appointments will overlap during transition periods to ensure continuity and smooth functioning of institutions. The common feature of all world-class institutions globally has indeed been the existence of strong self-governance and outstanding merit-based appointments of institutional leaders. It has been acknowledged that institutions in India are constantly plagued by excessive external interference. Leadership appointments in HEIs are mostly used as a mechanism to distribute favours. Unfortunately, self-governance and merit-based appointment of leadership have not been the norm in the majority of institutions of higher education in India. External influence has severely diluted the independence of institutions and brought in non-meritbased practices, demotivating their faculty from innovating in their curricula, pedagogical practices, research, and service initiatives. Institutions have also been severely disempowered by the rigid regulatory system of higher education. Decisions related to many fundamental local issues, which should naturally be within the purview of local governance and leadership, have been centralised at the level of the University Grants Commission or other bodies of the Centre and States. All this deeply undermines the principle of local governance and the local pursuit of innovation and excellence. HEIs in India should become independent self-governing institutions. Local and empowered Board of Governors consisting of highly qualified, competent and dedicated members will be constituted for governance. The board should be free from political or other interference, unbiased and public-spirited. The appointment of ViceChancellors who have high academic accomplishments and a proven ability to provide academic leadership has been the biggest challenge in the past.

To ensure hassle-free and effective implementation, an advisory institution, Rashtriya Shiksa Ayog (RSA) has been visualised. It is good that the role of the RSA under the chairmanship of the Union Minister of Education has been changed from regulatory to advisory to ensure the effective implementation of the NEP without delays. For financing education, the policy ‘unequivocally’ commits significant increase in funding of education by increasing budgetary support from central and state governments from 10% of the annual Budget to 20%, over a period of 10 years. However, the previous national commitment of 6% of the GDP has been given a decent burial. Private philanthropy will also be tapped for investment in education but it should not be allowed to become a pretext for the backdoor entry of private sector exploitation and commercialisation, as in the past.

But how can we operationalise these recommendations which appear utopian in the current Indian milieu? To ensure the availability of adequate financial resources for the implementation of the prescriptions which require a massive reorientation and upgrading of teaching competence and skills of the faculty, a conducive academic environment and culture of open and fearless intellectual discourse conducive to grappling with emerging intellectual, social and economic challenges to transform India into a knowledge society to meet the challenges of the 21st century is the moot question.

Our past experience informs us that, howsoever well-intentioned and well-meaning a public policy may be formulated, accepted and adopted by even enactment of a statute by the government, unless civil society acts as a watchdog and vanguard in the process of its implementation, vested interests will prevail, twist it to serve their interests, and make it ineffective.

Prof Surinder Kumar and Dr Kulwant Singh Nehra are associated with the Centre for Research in Rural and Industrial Development, Chandigarh.