Widening Childhood Vaccination Inequality in England Raises Concerns

Childhood vaccination programs have long been a cornerstone of public health in the United Kingdom, playing a pivotal role in preventing the spread of infectious diseases and reducing childhood mortality. However, recent years have seen a growing concern about widening inequalities in vaccination uptake, with certain groups of children in England being left behind. This widening gap in vaccination rates has raised alarms among public health experts, policymakers, and medical professionals, who fear that the UK could face a resurgence of vaccine-preventable diseases if the trend continues.

The National Health Service (NHS) in England has made significant efforts to promote childhood vaccination as part of a comprehensive immunization schedule. Yet, despite these efforts, a combination of socio-economic, cultural, and logistical barriers has led to disparities in vaccination coverage, particularly among children from disadvantaged backgrounds. This article explores the growing inequality in childhood vaccination rates in England, the underlying causes of this disparity, and the potential consequences for public health. It also discusses the measures that need to be taken to address this inequality and ensure that all children have access to life-saving vaccines.

The Importance of Childhood Vaccination

Vaccination is one of the most effective public health interventions available to prevent the spread of infectious diseases. For decades, vaccines have helped eradicate or significantly reduce the incidence of many deadly diseases, such as measles, mumps, rubella, diphtheria, polio, and pertussis. Childhood vaccinations have led to dramatic declines in the number of cases and deaths from these diseases, contributing to overall improvements in public health and life expectancy.

In the UK, the NHS provides a comprehensive vaccination schedule for children, with vaccinations offered for a range of diseases, including the six-in-one vaccine (for diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough, polio, Haemophilus influenzae type b, and hepatitis B), the MMR vaccine (for measles, mumps, and rubella), and the HPV vaccine (for human papillomavirus). These vaccines are offered free of charge as part of the NHS’s commitment to protecting public health. However, vaccination coverage must reach high levels—typically above 95%—to create herd immunity and protect those who cannot be vaccinated, such as infants and individuals with certain medical conditions.

The goal of universal vaccination is to ensure that all children, regardless of their socio-economic background, receive these life-saving vaccines. However, in recent years, concerns have grown about significant variations in vaccination uptake across different socio-economic groups.

The Growing Inequality in Vaccination Rates

Recent data from the UK’s Department of Health and Social Care highlights a troubling trend: childhood vaccination rates have been steadily declining in certain regions, with a widening gap between different socio-economic groups. A study published by the NHS in 2021 found that while vaccination rates remain high in some areas, others, particularly in lower-income or more ethnically diverse communities, have seen significant declines in coverage.

In particular, children from poorer households or those living in deprived areas are less likely to receive their vaccinations on time. For example, areas with higher levels of poverty, including some parts of London and the North East of England, have seen lower rates of vaccination for the MMR vaccine, which protects against measles, mumps, and rubella. In contrast, wealthier areas tend to have higher vaccination rates, often exceeding the 95% threshold necessary for herd immunity.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these inequalities, with many routine childhood vaccinations delayed or missed due to lockdowns, school closures, and restrictions on healthcare services. Parents of vulnerable children may face additional barriers in accessing healthcare, such as financial constraints, lack of transportation, and limited access to healthcare providers. These factors have compounded the existing inequalities in vaccination uptake and placed certain communities at even greater risk of vaccine-preventable diseases.

Underlying Causes of Vaccination Inequality

The widening inequality in childhood vaccination rates is the result of a complex interplay of social, economic, and cultural factors. Understanding these underlying causes is essential in addressing the disparities and ensuring that all children are protected from preventable diseases.

1. Socio-Economic Factors

One of the most significant drivers of vaccination inequality is socio-economic status. Families living in poverty or experiencing financial hardship often face additional barriers to accessing healthcare services, including vaccinations. The cost of travel to vaccination clinics, the time required to attend appointments, and a lack of knowledge about the importance of vaccination can deter low-income families from seeking timely immunization for their children.

In many cases, parents in lower socio-economic groups may also have less access to information about the benefits of vaccination or may be less likely to trust healthcare services. They may be more reliant on public health messaging and outreach, which may not always be tailored to their specific needs or challenges.

2. Ethnic and Cultural Factors

Cultural attitudes toward vaccination also play a significant role in vaccine uptake. Certain ethnic minority communities in the UK may have lower vaccination rates due to a combination of factors, including mistrust of the healthcare system, language barriers, and cultural beliefs about immunization. For example, some communities may have concerns about vaccine safety or may not be aware of the specific vaccines recommended for children.

Research has shown that there are notable differences in vaccination rates among children from different ethnic backgrounds, with children from Black, Asian, and minority ethnic (BAME) communities being less likely to receive their vaccinations on time compared to children from White British backgrounds. These disparities are often linked to historical and cultural factors that influence health beliefs and practices, as well as structural issues such as a lack of culturally competent healthcare providers.

3. Health System and Access to Healthcare

Access to healthcare is another critical factor contributing to vaccination inequality. Although the NHS provides universal healthcare, there are still significant disparities in access to services. Families living in rural or isolated areas may find it difficult to travel to vaccination clinics, while those with limited access to primary care providers may experience delays in getting their children vaccinated.

The COVID-19 pandemic has further highlighted the challenges in accessing healthcare, as routine vaccination appointments were disrupted during lockdowns. Many healthcare services were diverted to focus on COVID-19, leading to a backlog of routine vaccinations and a delay in childhood immunization schedules. In some cases, parents may have postponed or missed vaccination appointments due to concerns about potential exposure to the virus in healthcare settings.

4. Vaccine Hesitancy and Misinformation

Vaccine hesitancy, or the reluctance to vaccinate despite the availability of vaccines, is a growing concern globally. In the UK, vaccine hesitancy has been identified as a significant barrier to achieving high vaccination coverage rates. This reluctance is often driven by misinformation, fear of side effects, and mistrust in the safety and efficacy of vaccines.

Anti-vaccine rhetoric, particularly on social media, has contributed to the spread of misinformation about childhood vaccines. This misinformation can undermine public confidence in vaccination programs and influence parents’ decisions to delay or refuse immunization for their children. Communities that are already vulnerable due to socio-economic or cultural factors are more susceptible to these messages, which can exacerbate existing health inequalities.

Consequences of Widening Vaccination Inequality

The widening gap in childhood vaccination rates has significant implications for public health. As vaccination coverage decreases in certain communities, the risk of outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases increases. This could lead to a resurgence of diseases such as measles, which had been almost eliminated in the UK but has seen a rise in recent years due to falling vaccination rates.

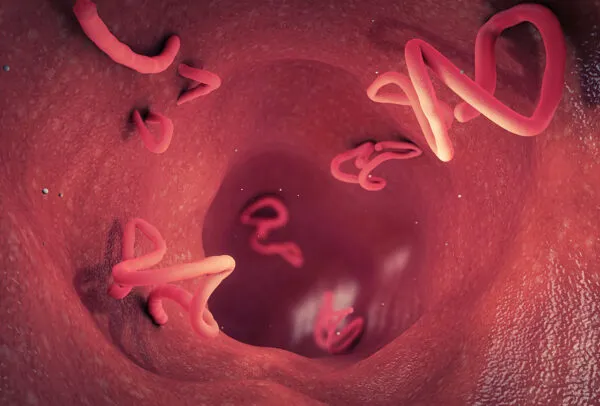

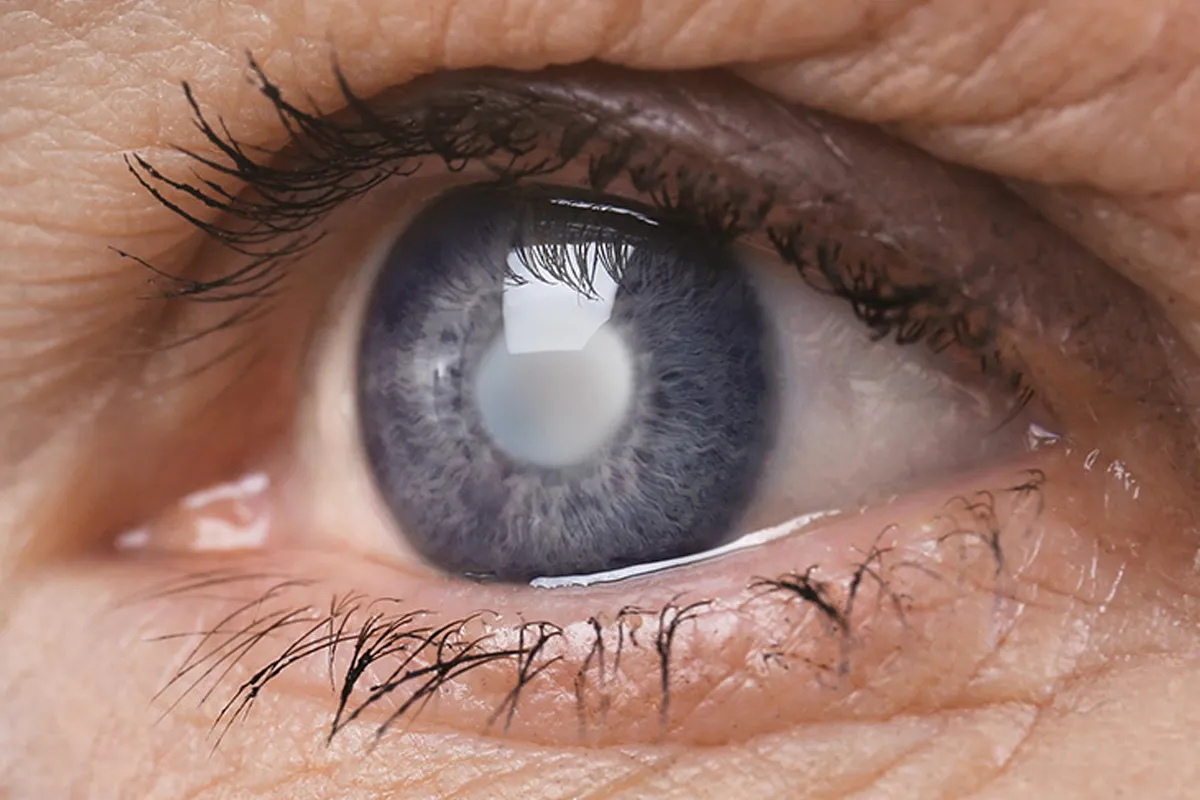

Children who are not vaccinated are also at greater risk of suffering from severe illness and complications from vaccine-preventable diseases. For example, measles can cause serious complications such as pneumonia, encephalitis, and death, particularly in young children or those with weakened immune systems. These health risks highlight the urgent need to address vaccination inequalities to protect all children from preventable harm.

Moreover, outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases not only affect the unvaccinated individuals but also put vulnerable groups at risk, including infants too young to be vaccinated and individuals with medical conditions that prevent them from receiving vaccines. This creates a public health burden that could have long-lasting consequences for the NHS and society at large.

Addressing the Inequality: Potential Solutions

To address the widening inequality in childhood vaccination rates, a multi-faceted approach is required. The following strategies could help reduce the disparities and ensure that all children receive the vaccines they need to stay healthy.

1. Targeted Public Health Campaigns

Public health campaigns should focus on increasing awareness about the importance of vaccination, particularly in disadvantaged communities. These campaigns should be tailored to specific populations, addressing the unique barriers and concerns faced by different groups. Messaging should be culturally sensitive, provide clear information about vaccine safety, and highlight the importance of vaccination for both individual and community health.

2. Improving Access to Healthcare Services

Efforts to improve access to healthcare services, particularly in rural and deprived areas, are essential to increasing vaccination rates. Mobile vaccination clinics, extended clinic hours, and home visits could help families who face barriers in accessing traditional healthcare services. Additionally, providing vaccinations in schools, community centers, and other accessible locations could make it easier for parents to get their children vaccinated.

3. Building Trust and Combatting Misinformation

Building trust between healthcare providers and communities is crucial in addressing vaccine hesitancy. Healthcare professionals should engage in open and respectful conversations with parents, addressing their concerns and providing accurate information about vaccines. Efforts to combat misinformation, particularly on social media, should focus on providing evidence-based facts about vaccine safety and efficacy.

4. Strengthening Healthcare System Support

The NHS should continue to prioritize childhood vaccination as an essential service, ensuring that routine immunization schedules are maintained even during public health emergencies such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Additional resources should be allocated to ensure that children in underserved areas have access to timely vaccinations.