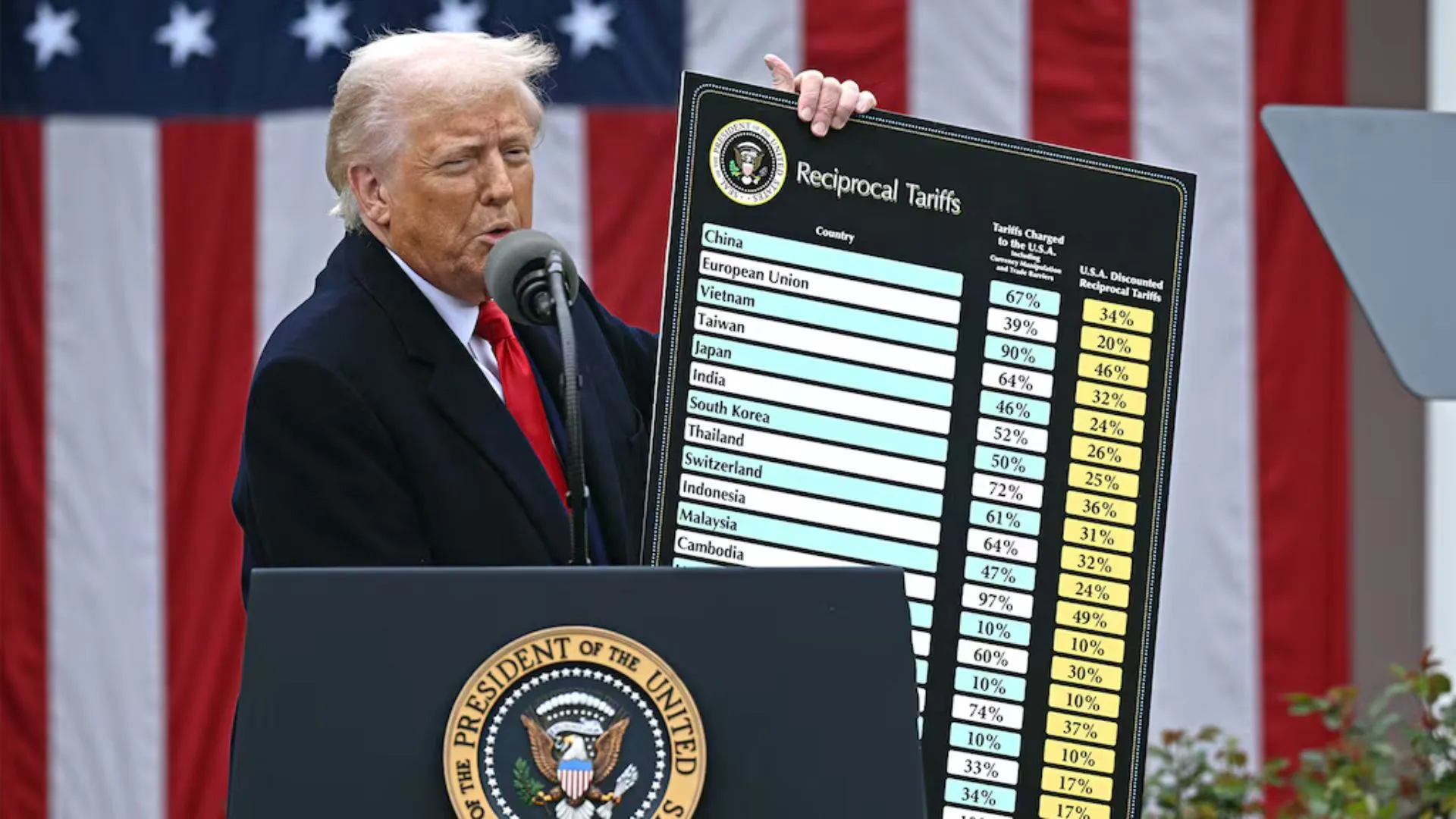

US President Donald Trump presented his very contentious ‘Liberation Day’ trade plan on April 2, calling for a 10% reciprocal tariff on everything imported. While the statement reverberated throughout world commerce, the fashion industry probably most directly and severely experienced the impact. Fashion companies are now working frantically to balance interrupted supply networks and increasing operating expenses as governments impose higher duties on major garment-exporting nations.

Fashion stocks respond fast

The financial damage was quick. Major fashion stocks crashed within hours of Trump’s remark. Luluemon fell even more in after-hours trading by 10 percent; Nike dropped by 7. Even German sportswear behemoths were affected—Adidas fell 12% and Puma SE dropped 14% on the Frankfurt stock exchange.

H&M, which relies heavily on suppliers in China and Bangladesh, fell by 5%, while US retail behemoths Amazon and Target reported drops of 8% and 10% respectively.

The United States Fashion Industry Association expressed deep concern in a public statement:

“We are deeply disappointed by the Trump Administration’s decision to impose new tariffs on all imports. This action will particularly affect American fashion brands and retailers.”

Where Does America Get Its Clothes?

To understand why the fashion industry is rattled, it’s crucial to examine where the US sources its clothing and footwear. A 2024 report from the American Apparel & Footwear Association revealed a stark truth—97% of all clothes and shoes sold in the US are imported. Only 3% are manufactured domestically.

Here’s how the top exporters break down:

-

China: 28.7%

-

Vietnam: 25.4%

-

Bangladesh: 7.8%

-

Indonesia: 7.3%

-

India: 5.6%

These countries now face steep tariffs under Trump’s plan, which aims to penalize nations with large trade surpluses against the US. China, already bearing a 20% tariff, will now see an additional 34% added, making the total duty a staggering 54%. Vietnam faces a 46% tariff, while Cambodia and Bangladesh have been slapped with 49% and 37% respectively.

Other nations like Pakistan, Taiwan, and even the European Union haven’t been spared, facing duties between 20% and 32%.

Why the Tariffs Hurt So Much

The fashion industry is uniquely vulnerable to import restrictions. Unlike other sectors that may have partial domestic production or alternate suppliers, apparel brands rely heavily on long-standing international supply chains, particularly in Asia, due to lower labor and production costs.

Mary Ross Gilbert, a senior analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence, explained:

“Apparel brands will most certainly be forced to raise prices.”

This isn’t just a short-term concern. Brands will need to revise their entire sourcing strategies, pricing models, and production timelines. Clothing retailers, especially those in the mid and lower price segments, are likely to feel the most pain, as cost-sensitive consumers may reduce spending.

Noted designer Rebecca Minkoff echoed this sentiment in a conversation with Yahoo Finance:

“Everything is going to be more expensive.”

Inflation and Consumer Reaction

The tariffs are also arriving at a time when US consumers are already grappling with inflation. Increased costs on clothing will further strain household budgets.

Rita McGrath, professor at Columbia Business School, told Vogue Business:

“Consumers are being hit by increased costs across many categories, which could affect the share of wallet dedicated to apparel.”

Analysts at UBS, led by Jay Sole, also released a sobering outlook:

“Given how extensive the list of tariffs is, the industry will realise there are few ways to mitigate the impact in the medium term other than by raising prices.”

Why “Made in USA” Isn’t a Quick Fix

In theory, shifting production to the United States could avoid tariffs. But in practice, this solution is far from simple. Manufacturing facilities can’t be built overnight. It takes months, if not years, to establish a supply base, secure skilled labor, and ensure product quality.

Moreover, domestic labor costs are exponentially higher than those in countries like Vietnam or Bangladesh, making US manufacturing financially unsustainable for most fashion brands, particularly in the fast fashion space.

Some brands also believe domestic manufacturing doesn’t align with their identity. Luxury group Kering, for instance, prefers keeping production rooted in European craftsmanship. CEO Francois-Henri Pinault told Business of Fashion:

“We’re producing in Italy and in France… we’re selling a part of our culture.”

How the Industry Plans to Adapt

Industry insiders suggest that brands may consider sourcing from countries less affected by the tariffs or shift to automation in the long run. However, short-term adjustments are limited, and price hikes appear inevitable.

Fashion retailers are now expected to:

-

Pass some of the increased cost to consumers

-

Absorb part of the expense in profit margins

-

Reduce order quantities

-

Look for alternative sourcing options in Latin America or Africa

But all these measures come with challenges, from logistic complications to capacity limitations in alternative regions.

What This Means for the Future of Fashion

Trump’s aggressive tariff strategy, while aimed at boosting domestic industry and protecting American jobs, has inadvertently placed the fashion sector in a precarious position. The dependence on global supply chains, razor-thin profit margins, and cost-conscious consumers make the apparel industry particularly sensitive to such policy changes.

Experts suggest that unless the administration provides relief through tax incentives or subsidies, or unless brands find innovative supply strategies, fashion will become more expensive for Americans in the near future.

In the end, the industry may be forced to reimagine itself—from where it sources materials to how it prices its products. But for now, the tariffs are set to test the resilience and adaptability of even the most established fashion brands. Whether this leads to a long-term transformation or short-term disruption remains to be seen.