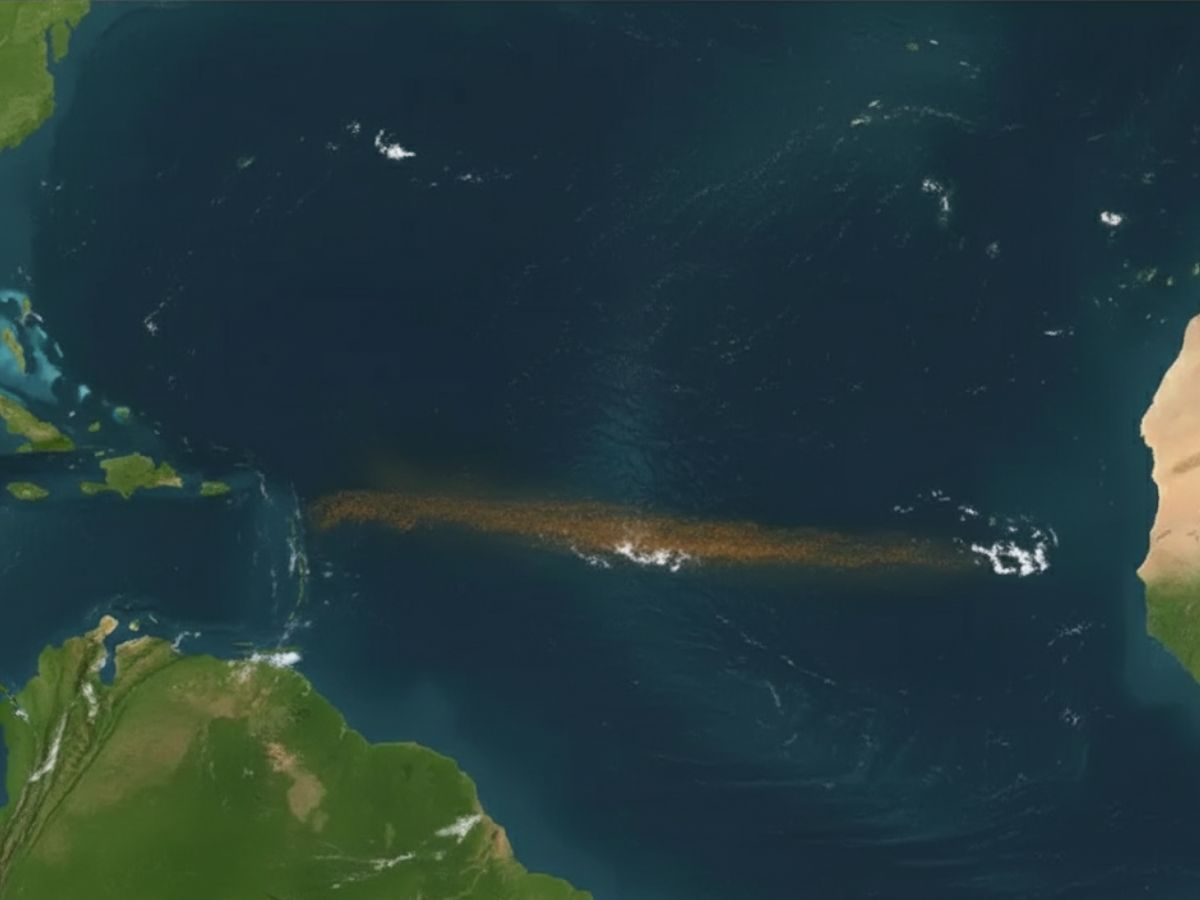

For the last 15 years, scientists have observed a massive stretch of floating seaweed connecting Africa’s west coast to the Gulf of Mexico. From space, it looks like a giant brown “ribbon” twisting across the Atlantic Ocean. Satellite images captured in May revealed that this floating belt—made entirely of sargassum algae—now weighs over 37.5 million tonnes and spans 8,850 kilometers.

This phenomenon, known as the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt (GASB), was first identified as a major bloom in 2011. What was once limited to the nutrient-poor Sargasso Sea has evolved into a vast chain nearly twice the width of the North American continent. It is both a natural wonder and a growing worldwide worry, according to scientists.

Why Is It Growing So Fast?

Sargassum typically thrives in warm, saline waters low in nutrients. However, in the last ten years, these algae have become more prevalent in nutrient-rich streams that are high in phosphate and nitrogen. According to a study published in Harmful Algae by the Harbour Branch Oceanographic Institute at Florida Atlantic University, between 1980 and 2020, nitrogen content within sargassum tissue rose by 55 percent, while the nitrogen-to-phosphorus ratio increased by 50 percent.

This nutrient overload originates from land-based sources—mainly agricultural runoff, wastewater discharge, and airborne pollutants. The Amazon River, in particular, contributes heavily to the nutrient load. The algae are then carried westward by ocean currents like the Gulf Stream and the Loop Current, which unite large marine regions into a single, continuous floating mass.

What Does It Mean for Marine Life?

It’s interesting to note that a rich ecosystem is also maintained in the Sargassum Belt. Tiny crabs, shrimp, eels, turtles, and even certain fish species find refuge and breeding grounds there. It functions as a “floating forest,” creating a lively ecosystem in parts of the ocean that usually have little life.

But the situation becomes complex when this growth turns excessive. Thick layers of sargassum block sunlight, stopping coral reefs from getting the light they need to make food. This harms ocean animals and lowers the sea’s capacity to absorb carbon.

What Happens When It Reaches the Coast?

When sargassum drifts ashore, the story changes drastically. Its dense masses rot on beaches, emitting hydrogen sulfide and methane—gases with a toxic smell and harmful impact on local air quality. Coastal regions depend heavily on tourism and fisheries, both of which face disruption. Cleanup operations are expensive, sometimes running into millions of dollars annually.

Sometimes, the damage spreads past the shoreline. In 1991, heavy sargassum buildup in Florida even caused a nuclear power plant to close for a while because the seaweed clogged its cooling system.

Also Read: Odisha Imposes 36-Hour Curfew in Cuttack After Idol Immersion Violence

What Does the Future Hold?

Experts caution that the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt may expand further due to global ocean warming. Shifts in winds and ocean currents could move it north of its usual Sargasso Sea area.

Experts fear that this trend could become the new normal, with massive blooms recurring more frequently each year. The once-stable Sargasso ecosystem now reflects the delicate relationship between human activity, nutrient cycles, and oceanic change.