From the distant fort of Bhainsrorgarh, surrounded by the Chambal river, comes a timeless kitchen tale, told with total reverence by the scion of its legacy, Kunwar Hemendra Singh of Bhainsrorgarh, and his stunning wife, Kunwarani Vrinda Kumari. Hemendra is a mystical chef who seems to communicate with every dish he creates, getting it finger-licking perfect each time..

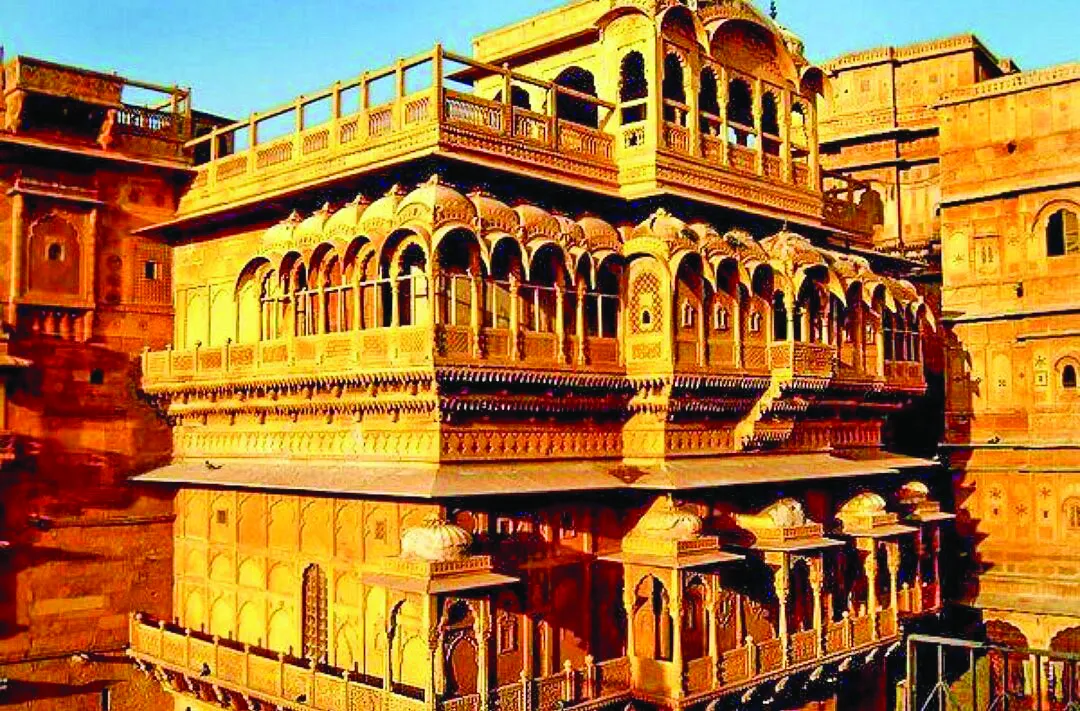

Bhainsrorgarh Fort, possibly the most picturesque of them all, and the home of Hemendra, was inhabited from at least the 2nd century BC. It stands tall between two rivers, Chambal and Bamani. Converted into a luxury resort, it is best known for its culinary tourism, with aspiring chefs booking personalised sessions with the master chef himself.

The fort held great importance for the Chundawat clan of the Sisodia Rajputs, as it was granted to Rao Chunda after he renounced the Mewar throne for his yet-to-be-born younger brother. As the eldest son of Rana Lakha, then ruler of Mewar, Chunda ji was the heir apparent to the throne of Chittor. The Chief of Bhainsrorgarh was counted among the 16 first class nobles of Mewar and was conferred the title of Rawat by the Maharana of Mewar.

Hemendra, the present-day heir to this legacy, regales his guests with not just fables from yore but also his inimitable Marwari silver service thali served on one of the majestic machans with a view of the crocodile-infested river.

A master of Marwari cuisine, he has quite a few aces in his culinary repertoire—many of which I have had the good fortune to taste. Be it his take on the Bidwal daal, mildly tempered, or his delectably flavoured Hara Maas, his favourite dessert, Amrit Gutka, that is chana daal halwa slow-cooked in a wok full of ghee and kilos of dry fruits over a fire, or even the splendid Chakki Ke Sule that never miss their texture.

Sule, or the Marwari take on skewered barbecue, is deeply rooted in the tradition of cooking by the campfire. Maas Ke Sule, made from soft and succulent boneless lamb is often replaced by paneer. In the case of flour-rich Mewar, the flour (besan) is intensely kneaded with ghee and then mildly flavoured, then shaped into soft squares and skewered over coal fire.

However, shikar or game cooking is his true forte and his Jungli Maas spells the coming together of ghee, garlic and red chillies. Passionate about every ingredient that goes into his dish, he is known to carry a suitcase full of masalas and rare ingredients whenever he helms a food festival or cooks in association with forums like Kitchen of the Kings or ITC Maurya Sheraton. However, besides his faithful cook, he and his petite wife do it all themselves – from getting the right cut of lamb, marinating the kebabs to cooking for over 300 guests.

In a chat with The Daily Guardian, the masterchef speaks on a few things that he is the most passionate about.

Q. How is it like to cook for large numbers, given that royal cooking is all about slow cooking and special ingredients? Can you keep the authenticity alive?

A. Cooking in large numbers is exciting as you can spread more love because of your food reaching out to larger numbers. If the focus is spot-on, bulk cooking turns out better. In bulk quantities, the weight helps slow cooking enhance the flavours and textures of the dish, especially when one is cooking meat.

Q. What’s your kitchen’s signature dish?

A. The Hari Mirchi Ka Maas. This dish has a unique taste that you cannot get in any other dish.

Q. How is Hari Mirch Ka Maas different from the famous Laal Maas?

A. The two dishes are poles apart. Hari Mirch Ka Maas is unique and exclusive as a dish and Laal Maas is the opposite, cooked in every household with a different recipe by each individual. Laal Maas is an over-hyped name in restaurants; the result of tourism in Rajasthan in the ‘90s, and people have started talking about a recipe of Laal Maas, which I feel is not correct, as there is nothing called Laal Maas. Laal Mas, like Dal Makhni or Butter Chicken, has a particular recipe which could differ maximum by 20 percent by individual chefs. I feel the very basic curry, using red chilli powder or paste with some curry cooked in most parts of North India, is Laal Maas (some people would laugh at this theory!). In earlier times, I remember the word Laal in Maas was used to differentiate between safed and laal. ‘What should we cook today? Laal or safaed?’ If safed, it could be Masale Wala, Kashmiri, Hari Mirch Ka, Khade Masale Ka, etc.

Q. As an avid cook and food traditionalist, how do you keep the balance between traditional recipes and innovation?

A. Traditional recipes are a part of our heritage. The collection of these recipes has been compiled by contributions from each generation in the past. Following tradition is one part and making tradition is another, which would be my contribution for the generations to come. There are some recipes of the past that I have found lacking somewhere or in which small innovations could bring out better results, so I experiment, and if the result is better to the palate, we make amends in the original recipe.

Q. If left in the kitchen for the whole day, what would you cook?

A. A kitchen is a great workshop and a lab for a person like me who used to dread science in school. It’s an art studio for me to create what I love and I would spend the whole day cooking, arranging, replenishing stocks, preparing my garam masalas, and finally, eating!