Forgotten and confined to oblivion, in a densely forested area of the Mangadh hills in the Banswara district of Rajasthan, bordering Gujarat lies the Mangadh Dham, a site of tremendous historical significance. It was this site that witnessed of one of the most horrendous massacres of innocent people in India’s colonial history.

On 17th November 1913, around 1500 Bhil Tribals, almost four times the number of martyrs at Jallianwala Bagh, were felled by bullets fired from the guns of soldiers of the British Army and Mewar Bhil Corps, supported by the forces from the princely states of Banswara, Santrampur, Dungarpur and Kushalgarh. Even though it took place some six years prior to infamous Jallianwala Bagh massacre, Mangadh Dham has come to be referred to as the Adivasi Jallianwala, a clear indication of the waves made by the Jallianwala Bagh episode, as compared to the low key repercussions of Mangadh.

The Bhils are an ancient tribe whose abode has essentially been in Rajasthan, Gujarat, northern Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, and parts of Sind. They eked out a living mainly as landless labourers, a great many forced into bonded labour under local zamindars. Exploited to the extreme, the tribe lived in abject poverty. Exacerbating matters further, the severe famine in 1899 – 1900, apart from claiming lakhs of lives, reduced the Bhils to the brink of starvation, compelling large sections of the tribe to resort to dacoity purely as a means of survival.

A glimmer of hope for the Bhils, to alleviate them from their sub human conditions, appeared when in the late 19th century, another tribal, Govind Giri, a social reformer, from the Banjara (wandering) tribe, launched the “Bhagat movement” aimed at emancipating the members of the tribe.

Devotion to and worship of agni or fire was a key principle of this socio religious movement. This necessitated the raising of sacred hearths called dhunis to perform the purifying Havans. In 1903, the main dhuni was set up on Mangadh Hill. Another noteworthy feature was that whoever became a follower of the Bhagat Movement had to vow to refrain from vices like alcoholism, substance abuse and gambling.

This movement succeeded in mobilizing the Bhils, who in 1910 placed a charter of 33 demands before the Government. The charter sought remedial measures for certain cardinal socio economic ills like ‘bet begaar’ or bonded labour, high taxes imposed on the Bhils and harassment of the movement’s followers by the British and rulers of the princely states. The Bhils went to the extent of composing songs emphasising determined defiance against the Imperial Government. A classic example was the one with the chorus “O’ Bhuretia nai manu re, nai manu (O› Britishers, we won›t bow before thee).

In November1913, a large number of Bhils had gathered at the Mangadh dhuni to perform a havan in protest against the refusal by the Imperial Government to consider their demands. The immediate provocation, resulting in the eventual massacre however, was an attack on a police station in the erstwhile Santrampur state near Mangadh. The attack led by Govind Giri’s second-in command Punja Dhirji Parghi, took the life of a police inspector, Gulmohammed. Simultaneously Bhil uprisings errupted in the princely states of Banswara, Santrampur, Dungarpur and Kushalgarh. An ultimatum served by the authorities on the Bhils to vacate Mangadh by November 15, was not adhered to.

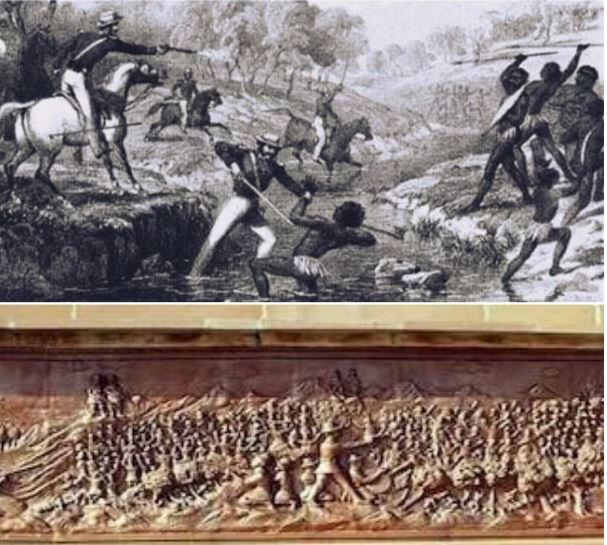

The Bhils on their part, had turned Mangadh Hill into a virtual fortress, and armed themselves with country-made guns, swords and other crude weapons. This set the alarm bells ringing among the local princes as fears of a unified armed rebellion loomed large. The British Political Regent. R. E. Hamilton initiated prompt punitive action. The combined forces of the British Indian army, the Mewar Bhil Corps and the four princely states, surrounded Mangadh.

Led by Colonel Sherton, assisted by Major Bailey and captain Stiley, the troops opened fire and finally perpetrated the massacre. Canon like guns were placed on the backs of donkeys and mules who were made to swivel in circles, with a view to enhancing the range of the firing, resulting in a higher number of casualties. The relentless firing was halted by a British officer only after he saw a Bhil child trying to suckle his dead mother.

The massacre so petrified the Bhils that they stopped visiting the Mangadh dhuni till several decades after Independence. Tiha, an aide of Govind Giri, killed in the massacre, was cremated in a jungle adjoining his home village. Today, a memorial named ‹Jagmandir Sat Ka Chopda› (Jagmandir, the place of true history), bears mute testimony to his supreme sacrifice and martyrdom.

Govind Giri was captured and sentenced to life imprisonment. Owing to his popularity and good conduct, he was released Jail in 1919 but banned from entering many of the princely states where he had a following. He finally settled down in Kamboi near Limbdi in Gujarat where he breathed his last in 1931. To this day, a large number of devotees visit Kamboi to pay homage at a temple constructed at the site of his samadhi.

Though far more enormous in dimensions than Jallianwala Bagh, this monumental tragedy has sadly been confined to the archives and perhaps the footnotes of history. Recently however, some steps have been taken to grant recognition and create awareness to the sacrifice made by the Bhils. The centenary of the Mangadh Massacre was commemorated by the Government Of Gujarat in 2013.

On the occasion, Narendra Modi the then Chief Minister of Gujarat, honoured Govind Giri›s grandson Man Singh while inaugurating a botanical garden named after the social reformer, on Mangadh Hill.

Whereas Jallianwala Bagh has won international acclaim, Mangadh Dham continues to be shrouded in obscurity. Unlike in the case of General Dyer, no official enquiry was held against the perpetrators of the massacre. Nor did the incident receive the kind of publicity that followed the Jallianwala Bagh tragedy. Also more recently, the former British Prime Minister, Theresa May tendered an apology on behalf of her country for the massacre at Jallianwala Bagh. Tribal leaders have demanded a similarly apology for Mangadh from the British Government.

Incidentally, under growing pressure from various tribal groups, the Government of Rajasthan erected a ‘Shaheed (Martyrs) Pillar’ and a statue of Govind Giri at the site of the massacre. Also in 2015 a university was named after Govind Giri at Godhra in Gujarat. The Bharatiya Tribal Party (BTP) has gone to the extent of demanding the creation of a separate tribal state ‘Bhil Pradesh’, comprising the tribal dominated districts of Rajasthan, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh, with Mangadh as its capital.

In addition, the tribal organisations have been demanding that November 17 be declared ‘Martyrs’ Day’, a tribute however small, to the innocent Bhils whose lives were sacrificed at the hands of the Imperial Government, and the significance of whose martyrdom seems to be lost for the future generations.