CDC Study Highlights Growing Tularemia Threat in Central U.S.

Tularemia, often referred to as “rabbit fever,” is a rare but potentially deadly infectious disease caused by the bacterium Francisella tularensis. While tularemia has historically been most common in rural areas, particularly in the central and northern United States, new research from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has brought attention to an alarming rise in cases, particularly in the central U.S. This emerging trend has raised concerns among public health officials, as tularemia is a zoonotic disease—one that can be transmitted from animals to humans—and its increasing prevalence poses significant risks to both public health and agriculture.

The CDC’s recent study sheds light on the growing tularemia threat in the central U.S., specifically identifying regions where the bacterium is now spreading more rapidly. By analyzing epidemiological trends, risk factors, and transmission routes, the CDC has provided a comprehensive look at the current state of tularemia in the U.S. and outlined strategies to mitigate its spread. In this article, we will explore the CDC’s findings, how tularemia spreads, and the potential health impacts of this rising threat.

What is Tularemia?

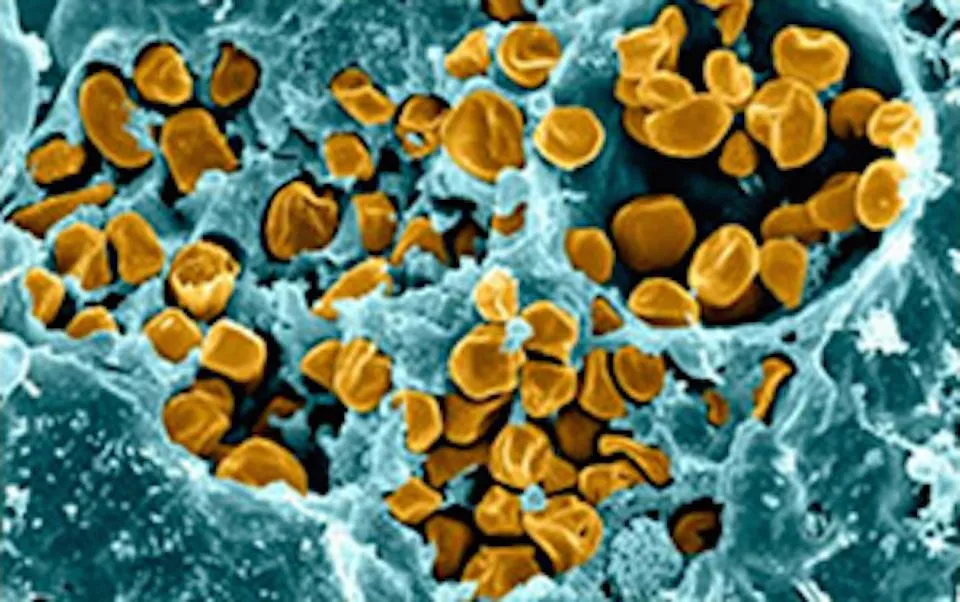

Tularemia is caused by Francisella tularensis, a highly infectious bacterium that primarily affects animals such as rabbits, hares, and rodents. However, it can also infect a wide range of other animals, including domestic pets and livestock. Humans can contract tularemia through direct contact with infected animals, inhalation of contaminated air or dust, ingestion of contaminated water or food, and through bites from infected insects like ticks and deer flies. The disease is most commonly associated with handling or consuming undercooked meat from infected animals.

There are several forms of tularemia, each with distinct symptoms, depending on the route of infection:

- Ulceroglandular Tularemia: The most common form, where an ulcer forms at the site of infection, typically following a bite from an infected insect or direct contact with infected animals. This form is often accompanied by swollen lymph nodes.

- Oculoglandular Tularemia: This form occurs when the bacterium infects the eyes, usually after a person touches their eyes with contaminated hands.

- Pneumonic Tularemia: The most severe form, where Francisella tularensis infects the lungs, often following inhalation of contaminated dust, aerosols, or droplets from infected animals.

- Typhoidal Tularemia: A rarer form with systemic symptoms and without the development of visible ulcers or lymphadenopathy.

Given the multiple ways in which tularemia can be transmitted, it has the potential to spread quickly under the right conditions, especially in areas where wildlife populations are high, and human-animal interactions are frequent.

CDC Study: Rising Tularemia Cases in the Central U.S.

In its recent study, the CDC identified a concerning uptick in tularemia cases in central U.S. states, particularly in rural areas where people are more likely to engage in outdoor activities like hunting, fishing, and farming. The study looked at data collected over several years and compared regional trends in tularemia incidence. The results showed that the incidence of tularemia has increased significantly in certain parts of the central U.S., prompting public health officials to take notice.

Tularemia is endemic in parts of the U.S., particularly in regions like Missouri, Arkansas, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Nebraska. Historically, these areas have seen relatively sporadic outbreaks. However, recent data suggests that tularemia may be spreading more widely, with reports of cases extending into new regions. In fact, there was a reported 50% increase in tularemia cases in some areas over the past five years.

The CDC attributes this rise in cases to several factors, including changing environmental conditions, increased human-wildlife interactions, and the presence of more vector species such as ticks and deer flies, which are known to transmit the bacteria. Additionally, climate change is suspected to be playing a role in the expanding range of tularemia, as warmer temperatures and altered precipitation patterns may encourage the proliferation of the ticks and flies that carry the disease.

Risk Factors for Tularemia Transmission

The CDC’s findings emphasize the key risk factors that contribute to tularemia’s spread. These include:

- Wildlife Exposure: People who live or work in areas with high populations of wildlife, such as rabbits, deer, and rodents, are at greater risk of exposure. Farmers, hunters, and trappers are particularly vulnerable because of their increased likelihood of handling animals or animal products that could be infected.

- Insect Bites: Ticks and deer flies are the primary insect vectors of tularemia. These insects can easily transmit the bacteria to humans during their feeding process. With rising populations of these insects in certain regions, people who spend time outdoors in areas with high tick and fly activity face a heightened risk.

- Climate Change: Shifting climate conditions, such as higher temperatures and more frequent rainfall, can create more favorable environments for ticks and flies to thrive. As these vectors spread into new areas, tularemia can follow, further expanding the disease’s reach.

- Increased Human Activity in Wildlife Habitats: As urban development continues to expand into rural and wilderness areas, more people are coming into contact with animals that could carry tularemia. Outdoor recreational activities, such as hiking, fishing, and hunting, may expose people to the bacterium.

- Livestock and Pet Exposure: While domestic animals like cats and dogs can get infected with tularemia, it is rare for humans to contract the disease from pets. However, livestock that are raised for food or fur can become infected, and improper handling of animal products or undercooked meat can lead to human infection.

Symptoms and Treatment of Tularemia

The symptoms of tularemia can vary depending on the form of the disease and the route of infection. In general, symptoms tend to appear 3-5 days after exposure to the bacterium, although they can develop as early as one day or as late as two weeks.

Common symptoms of tularemia include:

- Fever and chills

- Headache

- Fatigue and muscle aches

- Swollen and painful lymph nodes

- Skin ulcers (if exposed through a bite or injury)

- Sore throat or cough (in cases of pneumonic tularemia)

- Eye redness and irritation (in cases of oculoglandular tularemia)

Tularemia is treatable with antibiotics, and early diagnosis is key to preventing severe illness. The CDC recommends that people who have been exposed to tularemia, especially those with risk factors, seek medical attention immediately if they develop symptoms. The disease is highly treatable if caught early, but without treatment, tularemia can be fatal, particularly in its pneumonic form.

Public Health Implications of the Growing Threat

As tularemia cases continue to rise in the central U.S., public health authorities are ramping up efforts to monitor the disease and prevent further outbreaks. This includes:

- Surveillance: The CDC and state health departments have increased their surveillance of tularemia cases to better track the spread of the disease. By identifying patterns of infection and pinpointing areas with high transmission rates, they can implement targeted control measures.

- Public Awareness Campaigns: Educating the public about the risks of tularemia and how to protect themselves is a key component of disease prevention. The CDC has issued guidelines on how to minimize exposure to the bacterium, including wearing protective clothing when working with animals, using insect repellent to avoid tick and fly bites, and properly handling and cooking meat.

- Research: The CDC is investing in research to better understand the environmental and ecological factors that contribute to tularemia outbreaks. This includes studying the behavior of ticks and deer flies and how changes in the environment influence their populations.

- Vaccine Development: Currently, there is no vaccine for tularemia, but researchers are exploring the possibility of developing one. A vaccine would provide an essential tool in preventing the disease, particularly for people who are at high risk of exposure.

Preparing for the Tularemia Threat

The CDC’s study underscores the importance of addressing the rising threat of tularemia, particularly in the central U.S. While tularemia is still a relatively rare disease, its increasing incidence is a cause for concern. By understanding the risks and taking proactive measures, we can better protect ourselves and prevent the spread of this dangerous infection.

The continued monitoring of tularemia, along with increased public education and research into effective treatments and vaccines, is essential for managing this emerging threat. As climate change and human-wildlife interaction continue to shape the landscape of infectious diseases, tularemia may not be the only disease we need to watch closely. Public health agencies must remain vigilant and adapt to the changing dynamics of zoonotic diseases to safeguard public health.