‘The postulate is that some wrongdoers are sick while others are bad, and that it is against good morals to stigmatize the sick” (State v Guido)

The entire criminal jurisprudence rests upon the fundamental principle of actus non facit reum nisi mens sit rea, which means an act alone does not make anyone guilty unless there is a criminal intent. Substantiating the imperativeness of Mens Rea in a crime, Lord Diplock had quoted, “An act does not make a man blameworthy or guilty of a crime unless his mind is also guilty.”

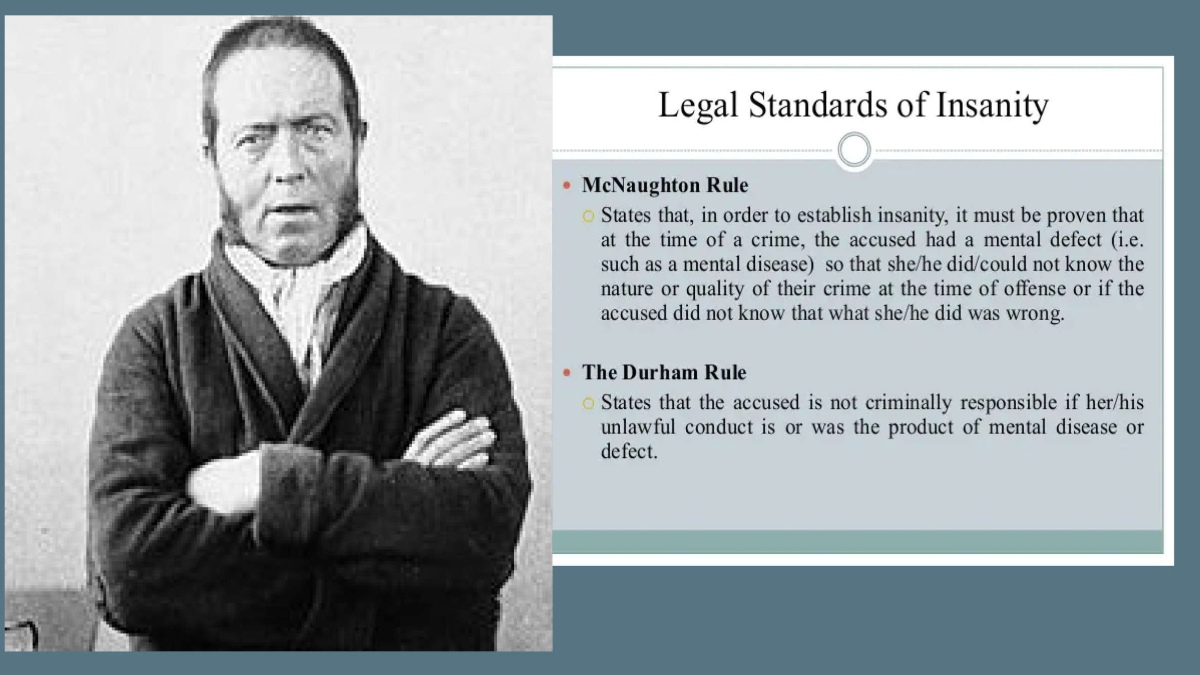

In a Criminal trial, it is this proposition of Mens Rea that defendants seek to challenge by claiming the defence of ‘insanity’ and if court accepts the defence, it exonerates the accused of any criminal liability that he has against him. The rationale of Insanity as a defence in India is formulated from the ‘McNaughton rule’ and is incorporated in Section 84 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860. The purpose of this article is to study the origin of this rule, examine its status quo in India and some major democracies and to analyse its actual relevance in the contemporary Indian society.

THE ORIGIN OF INSANITY AS A DEFENCE:

‘Insanity’ as a defence marked its inception from the case of R v Arnold (1724). This case led to the development of the ‘Wild Beast Test’ which examined the mental capacity of the accused in understanding the nature of his act and his ability to distinguish between ‘good’ and ‘bad’. In addition to this, the case of R v Hadfield (1800), created another test known as ‘Insane Delusion Test’ to prove the same.But both these tests turned out to be arbitrary and ineffective in establishing insanity.

R v McNaughton (1843), however, was the landmark case that engendered the ‘Right and Wrong Test’ under the ‘McNaughton’s Rule’ and marked the true genesis of ‘Insanity’ as a defence. The facts of the case are: Daniel McNaughton, a woodworker from Glasgow, Scotland attempted to assassinate the British Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel. He believed that the Troy Political Party spearheaded by Sir Reel wanted to murder him. However, he mistook Edward Drummond, the Prime Minister’s Secretary as the Prime Minister and shot him dead. During the trial, Daniel McNaughton’s attorney argued that Mr Daniel believed that he was being persecuted by the Troy political party. On that account, his attorney was able to prove his mental disorder of delusion and subsequently, his inability to form any Mens Rea necessary for that murder. Ergo, the jury found Mr McNaughton not guilty. The verdict formulated the maiden legal definition of ‘insanity’ and laid the principles of the ‘McNaughton’s Rule’. The principles were:

All are to be considered sane and having reason until proved otherwise,

It must be clearly shown that during the conduct of his act, the accused was working under the defect of reason, and

He didn’t know the nature and qualities of his act.

APPLICABILITY OF THE MCNAUGHTON’S RULE IN INDIA:

Section 84 of the Indian Penal Code 1860, embodies the principles laid down in the McNaughton’s rule and describes insanity as unsoundness of mind. It reads as:

“Nothing is an offence which is done by a person who, at the time of doing it, by reason of unsoundness of mind, is incapable of knowing the nature of the act, or that he is doing what is either wrong or contrary to law.”

‘Unsoundness of mind’ refers to a mental state when a person is incapable of understanding the nature of his act and realising what he is doing is wrong or contrary to law. The concept of furiosus nulla voluntas est established in Hazara Singh v The State means ‘a madman has no will’. A madman was interpreted as a mentally ill person. However, not all person with mental disorders can ipso facto claim this defence.A clearer interpretation of the issue was done in Bapu v The State of Rajasthan where the court established that ‘legal insanity’ is what needs to be proven and not ‘medical insanity’.

Further legal developments also clarified that a mere aberrant mind, which a lot of criminals have, does not attract unsoundness of mind.What needs to be established is the cognitive failure of the accused that made him incomprehensible of what he was doing was wrong. In Dulal Naik v State (1987)the McNaughton’s rule was interpretedalong withSection 105 of the Indian Evidence Actstating that courts presume a person to be sane and in full control of his faculties unless otherwise proven. Moreover, the burden of proof too lied with the accused.Also, the unsoundness of mind before or after the conduct of offence does not attract insanity as a defence. It has to be present during the offence.

INTERNATIONAL STATUS OF THE MCNAUGHTON’S RULE:

The McNaughton’s rule was censured from its very inception in 1843 and the House of Lords demanded a clear and reliable rule. Catering to their demands, in 1924, The UK government constituted the Atkin Committee to bring about changes in the rule. However, no considerable changes were brought. In 1953, The Royal Commission of Capital Punishment tried modifying the rule by adding that “insanity and irresponsibility were not to be treated as co-extensive” but this too was refuted by the Government.

However, a conclusive legislation was passed in 1957 known as The Homicide Act, 1957 and Section 2 of the said act precisely defined insanity. The Criminal Procedure (Insanity) Act, 1964 further clarified the procedure of trial and defence in similar cases. Subsequently, these laws came into force and the McNaughton’s rule was abolished.

The United States also followed McNaughton’s rule for the cases of insanity until 1954. Durham v. United States was a 1954 case where a new rule called the ‘Product Rule’ was established. However, the ‘ALI Rule’ (devised in United States v Brawner) overturned it in 1972. It followed the lines of the McNaughton’s Rule itself but significantly softened its stringency.

Nonetheless, even this rule was overridden by the Insanity Defence Reforms Act, 1984 which was developed in response to the case of United States V. John W. Hinckley Jr. (1982). GBMI (Guilty but Mentally Ill) was introduced and its norms were set stricter than the McNaughton’s Rule. A defendant who receives a GBMI verdict is sentenced in the same way as if he were found guilty. Considerable powers were given to courts in deciding the nature of the medical treatment and the sentence.

IS THE ‘MCNAUGHTON’S RULE’ ANTEDILUVIAN IN THE INDIAN CONTEXT?

Several Commonwealth countries including Australia and Canada have either abolished or considerably modified the McNaughton’s Rule. The UK itself, where this very rule originated, has abolished it. A lot of focus is given to psychiatry and the role of the courts in such cases. Nevertheless, The McNaughton’s Rule is still prevalent in India. The 42nd Law Commission of India did review this rule in 1958 but it suggested no noteworthy modifications and the law remained unchanged. Therefore, in the author’s opinion, it is primitive of the Indian Law System to still comply with this rule. But what should India do instead?

The government should develop Forensic Psychiatry Training Centre at Central level to properly assess insanity as a defence. Prison Mental Health Services should be initiated as recommended in the Bangalore Prison Study (2011). Moreover, systematic research should be conducted to bring about pragmatic and implementable laws for Insanity. In order to clear out the ambiguities in the law, Section 2 of the Homicide Act, 1957 (UK) and Section 4.02 of The Model Penal Code (US) gives a concise definition of Insanity and so should Section 84 of IPC. Some postulates of The Criminal Procedure Insanity Act 1964 and Insanity Defence Reforms Act, 1984 such as alter of offence from murder to manslaughter and additional powers to Jury, should also be considered for better implementation of these laws in the Indian context.

CONCLUSION:

Changing times demand adaptation and keeping abreast with it lays the foundation of a strong and flexible society. In that regard, sticking to a century-old archaic rule, such as the McNaughton’s, does not indicate a thriving legal system. A well-defined definition of ‘mental insanity’ is imperative to avoiding the controversies and scepticism related to the law.

Moreover, establishing a clear distinction between ‘legal insanity’ and ‘mental disease’ would make this law considerably viable for the accused. A well-researched and implementable set of laws for insanity is critical in correctly assessing such cases. Therefore, India should either modify section 84 of IPC or bring about fresh and practical legislation to deal with this ‘insane’ issue.

Several Commonwealth countries including Australia and Canada have either abolished or considerably modified the McNaughton’s Rule. The UK itself, where this very rule originated, has abolished it.