INTODUCTION Federalism in India refers to the relationship between union and the state governments of India or the distribution of power between central government and various constituent units of the country. Apart from the terms like quasi-federal (given by prof. KC Wheare) and pseudo-federal (given by Paul H Appleby) SC stated that India is the federation with strong centralizing tendency, mentioned under schedule VII of constitution of India that divides the subjects of legislation into three lists i.e., union, state and concurrent list. The union list (list 1) contains 97 items originally (100 subjects at present) and comprises of the subjects upon which only union government can make laws. State list (list 2) enumerates 66 items originally (61 subjects at present) upon which only state government can make laws. The concurrent list (list 3) is the most squabble provision for the functioning of union and state government as the 47 items originally (52 subjects at present) that are enumerated in this list confers concurrent power that either the union or state can make laws. So now, a fairminded question arises that if both union and state make a law on a particular matter mentioned under the concurrent list then what would be the consequence of that? Whose law will prevail over whom? This contemplates the legislative relation between union and state.

LEGISLATIVE RELATION BETWEEN UNION & STATE

Relation between the union and states are mentioned under part XI of the constitution of India that makes a two-way distribution of legislative powersi) With respect to territorial jurisdiction ii) With respect to subject matter of legislation Article 245 (1) confers power to the parliament for making laws to whole or any part of the territory of India and also the state legislature may made laws for whole or any part of the state. Thus, both parliament and state legislature have its own jurisdiction of making laws.

DOCTRINE OF TERRITORIAL NEXUS

Article 245 (2) talks about the extra territorial operation and stated that “no law made by the parliament shall be deemed to be invalid on the ground that it would have extra territorial operation.” The theory of territorial nexus shed light on the proviso that if any law made by the parliament which is out of the territorial jurisdiction shall not be invalidated. It was clearly mentioned in Wallace Bros. and Co. Ltd. vs Income Tax Commissioner, Bombay. In this case, a company was registered in England but appointed an agent in Bombay and carried on it’s business through this agent within the territory of India. According to the gross income, income tax authorities were tried to impose the tax but the company averred that the Indian income tax act, 1939 could not be enforced to it as it was concern to the English laws. However, the privy council ratify the levy of tax by exert the doctrine of territorial nexus and explains that it is not indispensable that the object to which law is activated should be tangible within the boundaries of the nation. But there should be a vinculum between the object and state making the law. The supreme court of India also applied the doctrine in State of Bombay vs R.M.D.C. where there was a sufficient nexus between the state of Bombay and the respondent who conducted the competitions in Bombay through the published newspaper having a wide circulation in Bombay due to which the state of Bombay entitled to impose the tax. Another principal constituent of the distribution of legislative power is its subject matter. The subject matter or the cause and object of a legislation dealt with the dual constitutional authority in case of concurrent list specifically. The differentiation of subject matter can not be appropriate in each and every circumstance and hence the interrogation arises by considering the constitutionality of the enactment. To resolve the uncertainty, courts apply various principles of interpretation.

DOCTRINE OF PITH AND SUBSTANCE

The doctrine of pith and substance introduced in Canada in a case Cushing vs Dupuy in 1880. Later on, this doctrine also made its way to India and prop up article 246 of the constitution of India. Doctrine of pith and substance is applied when there is a trespass of one legislature’s law over the other. In such cases, this doctrine is used to determine under which head of power a given piece of legislation falls. Pith and substance refer to the deep and pervasive enquiry. It means that in such cases of encroachment, a law should be read as a whole and not in sections, clauses or anyhow and need to check the object of newly formed law by other legislature. If that law is incidentally encroached and the object is in the people’s interest then that will be valid. For instance, in the case of Prafulla Kumar Mukherjee vs bank of Khulna, Bengal money lender act 1946 was stated to be valid by considering the doctrine of pith and substance. In this case, the maximum rate of interest and the maximum amount of interest is fixed which can be recovered from the debtor. The act is in regarding the money lending and money lender which is a state subject was considered as valid according to the pith and substance even though it is incidentally encroached a central subject. If in case of intentional encroachment, the law declared as null and void via the doctrine of repugnancy.

REPUGNANCY BETWEEN UNION LAW & STATE LAW

Article 254 (1) provides: “if any provision of a law made by the legislature of a state is repugnant to any provision of a law made by parliament which parliament is competent to enact, or to any provision of an existing law with respect to one of the matters enumerated in the concurrent list, then, subject to the provisions of clause (2), the law made by parliament, whether passed before or after the law made by the legislature of such state, or, as the case may be, the existing law, shall prevail and the law made by the legislature of the state shall, to the extent of repugnancy, be void.” Article 254 of the Indian constitution talks about the doctrine of repugnancy which arises when there is inconsistency or incompatibility between the central law and the law made by the state legislature and they are contradicting the provisions of each other. In such instances, the first occurrence is of harmoniously construction that is a principle which states to interpret the statute in such a way that neither of them will be nullified but in case they are totally contravening to each other then the doctrine of predominance of union over state follows i.e., the legislation made by union will prevail and state’s legislation will be repugnant. But there is an exception to this i.e., clause 2 of article 254. Article 254 (2) p r o – vides: “where a law made by the legislature of a state with respect to one of the matters enumerated in the concurrent list contains any provision repugnant to the provisions of an earlier law made by parliament or an existing law with respect to that matter, then, the law so made by the legislature of such state shall, if it has been reserved for the consideration of the president and has received his assent, prevail in that state.” It is clearly mentioned in the aforesaid provision that a state legislation can also prevail in that state if it received the assent of president later on. In Deep Chand vs state of UP, the state government introduced a new legislation i.e., UP transport services act whose provisions are different from the motor vehicle act therefore parliament amended the motor vehicle act in order to make a uniform law. But the court held that both laws are in direct conflict and occupied the same field so the state law was declared as void under article 254 to the extent of repugnancy to the union law whereas in the case of M Karunnanaidi vs uoi, the state law was prevailed as it was not in the direct conflict to the union law, in fact a complimentary act and the court held that the question of repugnancy arises only when two legislations are inconsistent or incompatible within the same field and cannot enact together.

POWER OF PARLIAMENT TO LEGISLATE ON MATTERS MENTIONED IN STATE LIST

The Indian Constitution is designed in unique way so as to enable the union more powerful even in making of legislation too. The parliament is empowered to make laws even on the matters mentioned in the state list in two situations stated under article 249 i.e., with respect to national interest and other under article 250 i.e., during emergency. The proclamation of emergency referred in this article must be a proclamation which may be made under article 352.

CONCLUSION

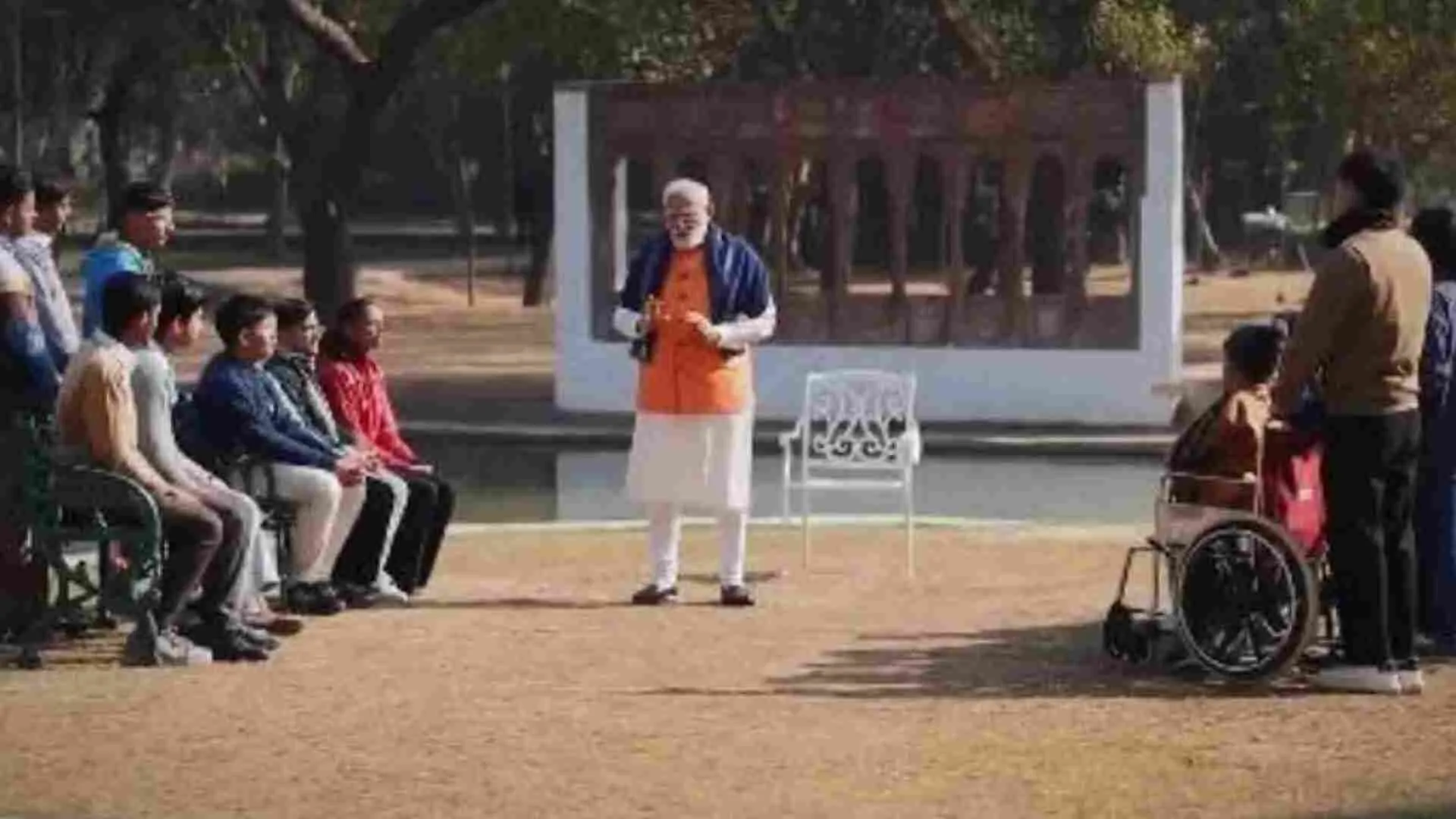

Our constitution is one of the very few that describes the relationship between union and state in detail. This centre- state relation derived from 56 articles in total i.e., article 245 to 300 in part XI and XII that differentiate into legislative, administrative and financial relation. Each legislature has their own dimension and sphere but, in few instances, the domain of union will prevail over state and that’s again corroborated evidence of the fact that India is federal with strong centralizing tendency. As Narendra Modi commented, “Federalism ….is no longer the fault line of Centre- state relations but the definition of a new partnership of team India.