15 August 1947 was a momentous day in the history of modern India. However, there isn’t much worth celebrating on that day. The passing of the Independence of India Act by the British Parliament on 18 July 1947 made provisions “for the setting up in India two independent Dominions”, namely India and Pakistan. The violence, however, both preceding and following Partition, is one of the worst tragedies of humankind.

Despite all the blood and gore that have come to be associated with Partition and the subsequent birth of the modern Republic of India in 1947, the scale of the horror is not known to many. Moreover, it is rarely talked about even in academic circles. In fact, a sustained narrative of euphoria was manufactured to suppress, and then eradicate completely from the consciousness of the masses, a compelling narrative of unimaginable physiopsychological wounds inflicted by Partition.

For British historians, there was an urge to show Partition as a benevolent act, a moral high ground of sorts, that despite 200 years of colonial rule, the civilised British could leave India as friends and even form a Commonwealth. Many others talked about Partition “as an illustration of the failure of the ‘modernising’ impact of colonial rule, an unpleasant blip on the transition from the colonial to the post-colonial worlds,” as wrote historian David Gilmartin in the Journal of Asian Studies (November 1998).

One would have hoped that Indian academicians, historians specifically, would look at Partition with a dispassionate expansive approach. However, the Indian academic class led primarily by Marxist-Nehruvian historians not only reduced Partition to a singular event on a calendar but also an outcome of a purely sectarian politics. For many “nationalist Indian historians”, writes Gilmartin, Partition “resulted from the distorting impact of colonialism itself on the transition to nationalism and modernity”. While Gilmartin may have diagnosed some of the characteristics of post-colonial history writing of Partition correctly, his characterisation of the Leftist-Nehruvian historians as ‘nationalist’ is not without criticism.

The Hindu-Muslim violence that engulfed the Indian subcontinent around the time of Partition was not an isolated event. The history of such violence is long and is rooted, at least in part, in the Islamic theology of iconoclasm and the notion of ‘kafirs’ (nonbelievers).

Despite the frequent and ad nauseam reminder of the ‘Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb’, the barbarism of the Islamic invaders is well documented. In most cases, the perpetrators and their agents themselves have left glowing accounts of the atrocities committed. Millions of idol-worshipping Hindus perished during the Islamic invasion. As historian Will Durant puts it: “The Islamic conquest of India is the bloodiest story in history.” Thousands of Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist temples were destroyed. Many more moortis were desecrated, dismembered, and demolished. Hindus were frequently subjected to the religious tax ‘jajiya’ in order to follow their faith and customs.

Hindus fought valiantly against their religious persecution. Stories of resistance are aplenty, mostly in the form of folklore, as historians have mostly ignored them owing to their ideological moorings. For example, there were frequent attempts involving common citizens to defend and protect Hindu temples and deities. Meenakshi Jain has meticulously collected those stories in her book Flight of Deities and Rebirth of Temples. Jain also writes about the Kashi riots (1809) — one of the earliest large-scale Hindu-Muslim violence on the records. It was a riot that lasted three days, there were losses “on both sides”, Jain quotes William Pinch (Hiding in Plain Sight; the Gosains on the Ghats).

About a century later in 1921, emboldened by the rising Muslim nationalism under the leadership of Muslim elites and scholars such as Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, Allama Iqbal, etc, the Moplah riots saw several hundred Hindus butchered in the Malabar region of Kerala. It was an open effort to set up an Islamic state in the area of coastal Kerala. “The blood-curdling atrocities committed by the Moplas in Malabar against Hindus were indescribable,” wrote B.R. Ambedkar in Pakistan or the Partition of India. Closer to Partition itself, on 16 August 1946, the ‘Direct Action Day’ of the Muslim League saw several hundred Hindus perish by the rioting mobs in Kolkata.

Viceroy Louis Mountbatten came to Delhi in March of 1947 with a mandate to end British rule as soon as possible and set a deadline of August 1947 for it. Cyril Radcliff, a British lawyer, arrived on his maiden trip to India to lead the Boundary Commission. With little knowledge of India’s history, culture, demography, and geography, Radcliff was tasked to redraw India’s map in a matter of days. When all was said and done, the sacred land of Bharat — the land of numerous Devis and Devatas; of Rishis and Acharyas; of myths and lore — was divided. Pakistan became a new country on 14 August and India became independent on 15 August 1947.

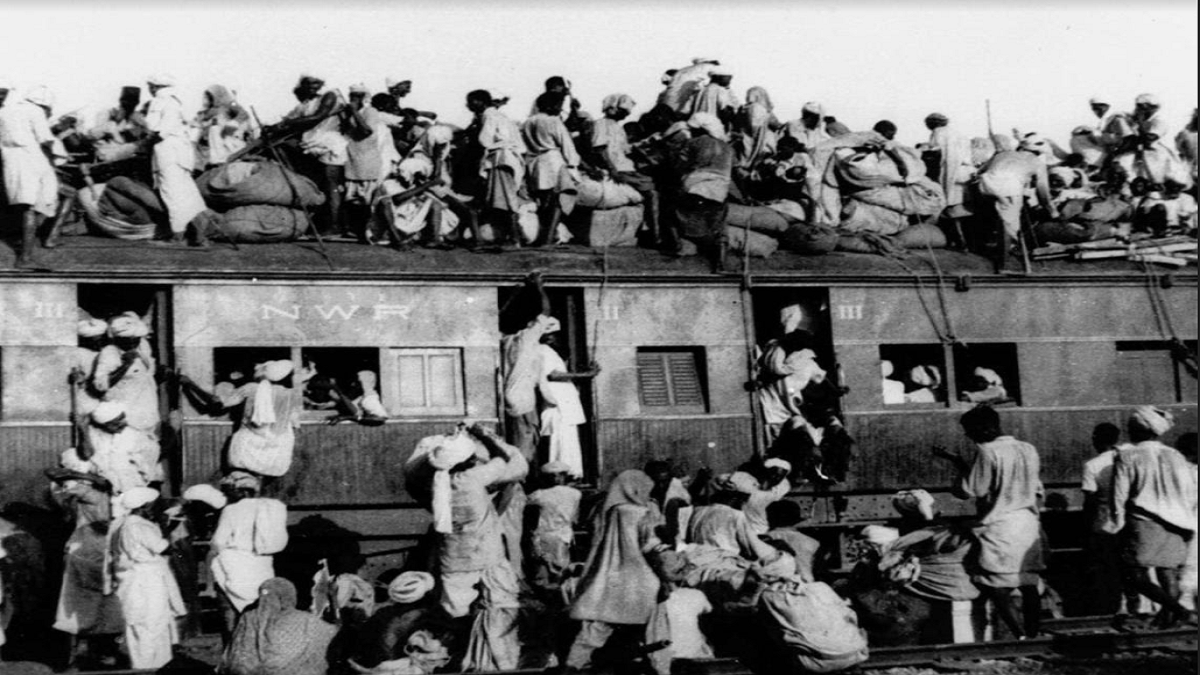

Nearly two million people lost their lives during Partition, according to some estimates. The real count could be much higher as usually is the case. It was the most horrific death nobody expected and none deserved. “Early in August 1947 things began to change,” wrote Khushwant Singh in his book Punjab, Punjabi, and Punjabiyat, “The riots assumed the magnitude of a massacre and it became clear that Sikhs and Hindus would have to clear out of Pakistan.” That fear forced one of the worst human migrations in history. It was a tragedy of epic proportions.

As the Indian subcontinent was split-based on religion — Hinduism and Islam — close to 14 million people found themselves in the wrong country and on the move overnight. Many started on an unknown journey — on foot or by trains — hoping they would return ‘home’ one day once the dust settled. After all, most of them had lived there for hundreds or even thousands of years. They belonged to the land which they protected and nurtured with their sweat and blood for their Dharma told them to protect their nation from all enemies with the help of both shastra (weapons) and shaastra (knowledge). It was the land that “bears traces of gods and footprints of heroes. Every place has its own stories, and conversely, every story in the vast storehouse of myth and legend has its place.” (Diana Eck’s A Sacred Geography).

People left their valuables behind, grabbing what they could for what they thought would be a short exile. They handed their house keys to their neighbours. “We picked up whatever we could in our hands, handed the keys of the house to a Muslim friend, Manzur Qadir, and joined the stream of Hindu and Sikh refugees going out of Pakistan to India… Then I realised that the world I had lived in and whose continuance I had taken for granted had ceased to exist,” writes Khushwant Singh of the ordeal.

Houses, big and small, were burnt down and looted, women were raped, children were separated from their family. Trains after trains arrived at stations overflowing with corpses. These passengers were killed by bloodthirsty mobs en route. They called it “ blood trains”, recounts Nisid Hajari in his book Midnight’s Furies: The Deadly Legacy of India’s Partition. Those “blood trains”, all too often, “crossed the border in funeral silence, blood seeping under their carriage door,” Hajari writes.

Amid the jubilation that followed the lowering of the Union Jack, the raising of the Indian Tiranga, Jawaharlal Nehru’s ‘tryst with destiny’ speech in Parliament, and the chanting of ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai’, there was a sense of loss, uncertainty and despondency. As Khushwant Singh would write, “The only person who seemed real was Mahatma Gandhi who had refused to participate in the festivities and was going about on foot from village to village exhorting people to stop killing neighbours.”

Avatans Kumar (Twitter @ avatans) writes frequently on the topics of Indic knowledge tradition, language, culture, and current affairs. He is a JNU and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign alumnus.